On the day Othman got his scars, he lost his mom, his brother, a cousin, and his will to speak.

It was late May 2016, and Othman was around three – no one knows exactly what day he was born. He was curled up on a mattress with his family, trying to ignore the sounds of war outside his small village near Fallujah. His baby brother, Louay, was sucking on a bottle, and his grandma, Hadoud, was in the next room, asking God to keep the fighting from coming any closer.

Her prayers were not answered. There were two loud booms, then screaming. Hadoud saw only dust and smoke. And then, by the light of a mobile phone, one of her grandsons pulled survivors and bodies out of the room where Othman had been trying to sleep.

Othman’s mother, Lina, brother Louay, and cousin Aisha were dead. He and his sister, Deena, who is less than a year younger than him, were bleeding from their bellies and faces. After a hasty burial, the surviving family members fled to a nearby village where, they had heard, the Iraqi army was waiting to bring them to safety as they escaped the control of so-called Islamic State.

When the family arrived, hundreds of men, including Othman’s grandfather and two uncles, were rounded up by militiamen and never seen again.

The family was bused to a desert camp, where they lived for months. When they finally made it home more than six months later, the room where Othman got his scars still smelled of burnt flesh.

By then, Othman, his face speckled black and abdomen embedded with shrapnel, had stopped speaking to almost everyone.

I met the boy I now know as Othman somewhere in the middle of his transition from regular old toddler with a sweet tooth (who his mom sometimes spanked when he was naughty) to timid five year old who seems sad most of the time.

The scars on his body were bright pink, and it looked as if he had bits of metal in his face.

It was autumn 2016 in Iraq’s western desert, and the camp where he had been sleeping for more than four months was crowded with people keen to tell a journalist (or maybe anyone at all) about the hell they had endured under so-called Islamic State, and then the hell they had gone through while fleeing to what they thought would be safety.

An estimated 3.2 million people were then displaced in Iraq – some to camps like Othman’s, called Ameriyat al-Fallujah, others to rented flats, still others to schools and mosque gardens. And in the midst of Iraq’s three-year war with IS, everyone had a story. But Othman was not telling his. He was placed in front of me and someone lifted his shirt and pulled down his trousers to show me the wounds on his abdomen.

A woman said that his mother was dead and his father missing. This was not unusual. In fact, as journalists and human rights watchdogs later reported, militias allied with the Iraqi army had taken hundreds of men from the village where these women were from – Saqlawiyah. “None of these children have fathers,” someone offered.

Othman didn’t answer my questions about his name, his age, or where he was from. What he did was stare straight ahead, holding tight to a packet of biscuits, unbothered by the trail of snot hanging from one nostril or by the beeping lens as I took pictures.

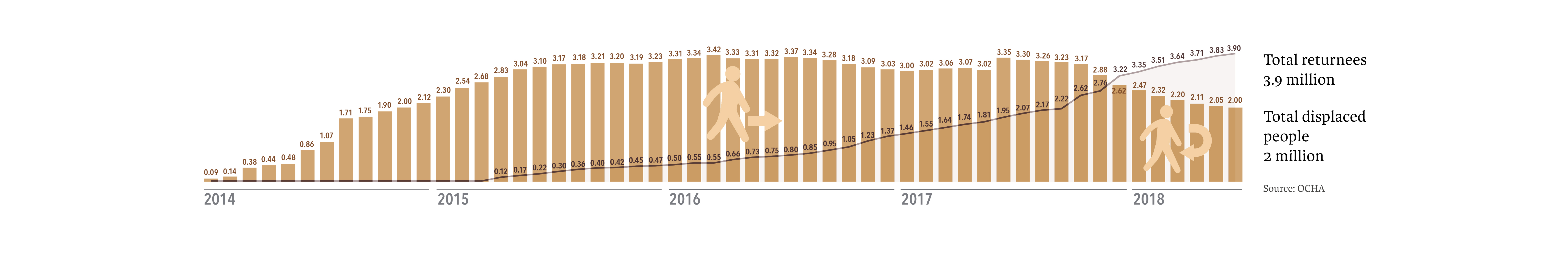

A year and a half later, IS had been defeated, and uprooted Iraqis like Othman were beginning to trickle home. There was no dearth of information on the six million people forced to flee their homes since IS first appeared, becoming what the UN calls internally displaced people, or IDPs. There were maps, graphs, and reports by aid agencies that documented who went where and when, with a specificity that sometimes beggars belief.

There were also particulars on the work of international and local aid organisations, who were attempting to provide food, safety, and shelter to the 11 million Iraqis who needed help at the worst points of the past years, with limited (and now shrinking) budgets.

What was harder to discern, with the numbers showing people returning in waves, was what displaced people were now heading back to. The stats didn’t offer many clues about what had happened to the kids who had lost parents, missed years of school, and spent years away from home.

I wondered most about what had happened to the boy whose name I did not know. So in April, I decided to go back and find one person in a country of 37 million.

Along the way I learned not only Othman’s name, but also how words like displacement, return, and war, so common in press releases and news articles, don’t even begin to express what the last few years have done to many Iraqis, and how hard it will be for many to break out of a long cycle of violence and build any semblance of a future.

Busy cafés, broken bridges

Today’s Iraq is much changed from 2016, when the battle for Mosul was still gearing up and some of the deadliest moments of the war against IS were still to come.

Othman is born

On the surface, at least, there are signs of recovery. IS, which swept through a third of the country in a matter of months in 2014, now holds no significant territory in Iraq. After months or years in temporary shelter, civilians are going home to those areas the group did hold: just over two million people are now displaced, compared to more than three million when I met Othman in October 2016.

The capital is safer than it has been in years. In October 2016, the UN recorded 1,120 civilian deaths and 1,005 injuries across Iraq – 268 and 807 of those in Baghdad province, respectively. This April, when I came back, the count was down to 68 civilian deaths and 122 injuries countrywide, with eight and 30 in Baghdad.

January 2014

Fallujah falls to IS

On a Friday morning at the city’s famous Shabandar Café, an intellectual hub that was blown up in the bad old days of sectarian violence in 2007 (no one ever claimed responsibility), men and women mix easily, drinking tea and smoking shisha.

Across the river in Anbar province, on the main drag in Fallujah – the city closest to Othman’s home and one of the first to fall to the IS militants – restaurants are also open, busy, and serving up their famous kebabs. The roads are even being paved and swept, paid for with UN funding.

And elections passed off peacefully in May – a few months before, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi was in Davos, announcing that Iraq was open for business and seeking around $100 billion to rebuild infrastructure and homes. The country eventually received $30 billion in pledged loans and international investment.

June 2014

Mosul falls to IS

IS declares caliphate

1.2 million displaced

But the reality isn’t quite that rosy: the polls themselves were marred by allegations of graft, and there’s talk of a recount; while the economic recovery has been fragile and uneven. Even with oil prices up and some new financial backing from abroad, many young, educated Iraqis still have visas on the brain, and there are growing signs of discontent at the slow pace of progress. In several southern cities, protesters are now taking to the streets, frustrated by joblessness, water shortages, and corruption.

Iraq’s post-war recovery feels slow for everyone, but for those – like Othman – who were forced out of their homes during conflict, their old lives seem increasingly distant and impossible to regain. The pace of returns is slowing and, in a recent survey of displaced Iraqis who do not live in camps (they are staying in rented homes, with host families, in unfinished buildings, and schools), only 30 percent of IDPs said they would even attempt to go back to their villages, towns, or cities in the next six months. They cited fear for their safety, destroyed homes, and a lack of job opportunities.

Places like the centre of Fallujah are making a comeback but, not far away, bridges are still split in half, and many of those who have gone home find they no longer have houses, jobs, or much in the way of a future. Some people even bring their tents with them, just in case.

Uthman and Othman

The first Othman, or at least the one people are named after, was Uthman ibn Affan, one of the earliest converts to Islam and the third leader of the Muslim community after the prophet Muhammad’s death in 632.

January 2015

2.2 million displaced

Shia Muslims (the majority in Iraq but the minority worldwide) believe the prophet’s cousin Ali ibn Talib Tabib should have been his successor. Instead, he had to wait to take the reins of the Muslim community until after Uthman was assassinated in 656. Sunnis consider the first 30 years after the prophet’s death (including Ali’s rule) to have been a glorious time for the nascent religion. Shias see the first three leaders (including Uthman) as illegitimate.

This all means Othman (in the slightly less old-fashioned spelling of the name) has a name with serious sectarian resonance, and in a time when brothers being named Uthman and Ali is largely gone.

These differences don’t necessarily matter in the day-to-day, especially in mixed cities and provinces where everyone is frustrated with the lack of decent jobs and the traffic, and friendships are forged, like everywhere, over football or coffee.

May 2015

Ramadi falls to IS

In fact, many pundits predicted, or at least hoped, that triumph over IS would be Iraq’s moment: a chance for economic recovery but also to overcome decades of religious resentment and violence. After all, the victims of IS came from all segments of society, and the country is now plastered with posters of martyrs who fought off the group; their names are Sunni, Shia, Christian, Kurdish, and Yazidi.

But sectarianism, which admittedly gets the blame for far too much in the Middle East, is still holding strong in some parts of Iraq that suffered the most under IS.

In Anbar province, where I met Othman, it’s the backdrop to everything politicians and leaders say: it’s been that way since the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003. Then, Shias took over as the country’s power brokers, first in an ostensibly secular government installed by the United States and its allies that in fact used a sectarian quota system that remains to this day, then as the result of elections – which members of many Sunni Anbar tribes boycotted back then. When leaders in Anbar talk about being hard done by Baghdad, they mean by the Shia leadership. When they talk of neglect by the central government, that’s a not so lightly veiled reference, too.

February 2016

Ramadi liberated

The history of these divisions is long and tied up in the early days of Islam, but modern-day resentment is more about class and power, and it doesn’t help that in politics, sectarianism is still the only game in town.

Chatham House’s Renad Mansour, an expert on Iraqi politics, points out that Iraqi leaders of all stripes actually encourage sectarianism, because they haven’t been able to deliver much that voters want and need. That would include things like better education or an improved health system – tellingly, Mansour notes, those in power send their kids abroad for school, or head to private clinics in Europe if they’re ill.

March 2016

3.4 million displaced

“The elite instrumentalise these identities to gain popularity,” Mansour says. “When you are unable to provide services or to be a good leader, the best way to keep your constituency is to use identity, and create fear, and create us and them. That’s a classic identity formation technique.”

Othman gets his scars

It’s one that has been especially successful in parts of Anbar. Shia leaders who speak the language of sectarianism are now poised to take more power on the national stage; that includes suit-wearing representatives of the Hashd al-Shaabi (Popular Mobilisation Units), the mostly Shia militias that allied with the Iraqi army to fight IS and are now technically under the government’s umbrella. So there’s a real fear that Othman’s province, the only one in Iraq that is majority Sunni, is due for a new rotation in the cycle of violence, displacement, return, and dissatisfaction that has been turning for years.

The state that called itself Islamic, itself born of this pattern, manipulated years of resentment to exert control over Sunnis, even as most of its victims were from their own sect. They even told terrified residents of Fallujah not to flee, that Shia militias would be waiting to exact revenge on them because of their sect.

In the case of Othman’s village and another one close by, that’s exactly what came to pass.

Thursday, 2 June 2016

What happened in Saqlawiyah and al-Sejar in the early days of June 2016, forever altering Othman’s life, has been well documented by journalists and human rights watchdogs. But two years later, the small details those who were there recall are still unsettling: a bracelet on a child’s wrist, the lights that illuminated the men before they vanished.

After months of domination by IS and a punishing siege, the villagers who remained on the outskirts of Fallujah (those who could afford to leave had gone long ago) heard that the Iraqi army had come to rescue them.

Wajriah Sleiman Nayef, who graciously opens her gate while I am knocking on doors in Saqlawiyah asking after Othman, explains what happened next; what UN human rights chief Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein described as “the worst – but far from the first – such incident involving unofficial militias fighting alongside government forces against ISIS.”

June 2016

Fallujah liberated

85,000 newly displaced

Othman flees to Saqlawiyah

He is bused to Ameriyat al-Fallujah

It was a Thursday, she recalls. The second of June, to be exact. She is speaking with me from a home she’s borrowing in Saqlawiyah – all the houses her family owns were destroyed in the war, including one next door that has a frontispiece and not much more.

The day before that Thursday, her husband, Oday Jabar Hussein, had tied a piece of string around their daughter Nabaa’s tiny wrist, a bit of fun to lighten up so much fear and to distract from the daily hustle of stretching to make little food feed five kids.

With heavy fighting under way, the family decided to make a break for it and succeeded in reaching the Iraqi Army soldiers, who, according to various eyewitness accounts, were joined by militiamen.

They were a large group on the run, including her husband’s brothers, their wives and children, and his parents. Her husband Oday “was walking in front of us, holding the little children,” Wajriah says.

October 2016

Battle for Mosul begins

The forces that met the villagers separated women, children, and the elderly from the men and boys. Wajriah recalls their instructions: “Women stay in the back; men come forward.” Oday left Nabaa and their other kid with her.

“The men moved forward and the security forces started searching them. The men sat down on one side and we sat down on another side. We could see them from a distance – there was a tank near them and bright lights pointed at them. And then, because lots of women were still arriving, we couldn’t see the men anymore.”

The women and children were bused to camps. Some of the men were tortured and returned to the custody of Anbar authorities; some were killed, and, according to the Saqlawiyah local council, 807 men are still missing. Other counts are lower – a committee formed by the Anbar governor says 49 of the men and boys are known to have been killed and 643 are missing. Another 73 are missing and 12 are dead from Othman’s village, al-Sejar. None of the men have ever officially been accused of any crime.

On that Thursday, Wajriah lost her husband, father, six brothers-in-law, six brothers, and two nephews.

Today, she lives with her husband’s mother, her sisters-in-law, and their children, including one baby boy who has never met his father. She says the adults “spend most of the days crying for our men,” although they try to curb it for the sake of the kids.

The children know something is wrong, and each deals with it in their own way. The oldest male in the house is Wajriah’s son Marwan, aged 11. He doesn’t talk much, and while his cousins gather in another room, he doesn’t wander far from his mom.

His younger brother Hamzeh sometimes stands in the street waiting for Oday. Since the family isn’t living in their own home, Hamzeh wants to be sure his dad knows where to find them when he comes back to them.

Nabaa, now five, tore the string off her wrist when she got tired of pining for Oday. Still, when Hamzeh asks where her dad is, she says flatly: “He went to the shop to buy some chocolates.”

In a back room of the house, Wajriah’s sisters-in-law and their children huddle around a cracked mobile phone, swiping through pictures of missing men.

One man poses on a shiny car, another wears mirrored sunglasses, his hair slicked back. A third sports a black shirt with the logo of Real Madrid, the Spanish football club that won the Champions League title a week before he disappeared.

At each picture, the women and children pause, wiping away tears as they identify the men by name or relation.

“Oday.”

“My dad,” Hamzeh chimes in.

“Ahmed.”

“My husband.”

“Abu Zaki.”

“My sister’s husband.”

“That’s my husband.”

The archivist of Saqlawiyah

I had assumed Othman’s father was missing like the other men of Saqlawiyah and al-Sejar, with no real hope he would ever come back.

But the unofficial archivist of Saqlawiyah, a 40-year-old mother of four who didn’t finish secondary school and keeps her records in a black laptop case even though she has no computer, quickly dispossessed me of that notion.

As Hajjar Salem Adnan ran from Saqlawiyah, losing her father, husband, brothers and an uncle “so old he doesn’t have any teeth”, she kept track of everything, becoming a one-woman documentation operation.

I saw the first of Hajjar’s notebooks when we met at Ameriyat al-Fallujah in 2016. She showed it to me – or rather waved it at me – in an effort to draw attention to the 705 members of her tribe who she counted as taken, each name and year of birth written neatly between the thin lines of a school exercise book.

Back then, Hajjar was livid that nobody seemed bothered by the missing men or that a bunch of fatherless families were stuck in the desert. Camp life was hard – hot in the summer, cold in the winter. Hajjar calls her stay there humiliating, waiting for clearance from the authorities to leave. Naturally, she still has the small blue permission paper she was waiting for. She spent much of her time “chasing the government, asking for answers and resources for our family.”

She has remained a thorn in the side of officials in Saqlawiyah, Baghdad, Ramadi, and Fallujah, where she now lives with her mother and children. “Everyone we asked about our people would just say, ‘they were either killed or will be missing forever, we don’t know’.”

Hajjar brooks no excuses for officials, from the local council straight up to the top. “If there was a real government, they would tell us ‘your husband is dead, you don’t need to look for him’… then we could mourn.”

While she’s got nowhere with the authorities, Hajjar says some of her note-taking and record-keeping has just been “to remember” what happened to her family and friends. While she waited it out in the camp, Hajjar noted the people she met, where they had gone, and their phone numbers. She sometimes even kept copies of their IDs, folded into the pages of school exercise books.

“If there was a real government, they would tell us ‘your husband is dead, you don’t need to look for him'… then we could mourn.”

Her meticulousness came in handy when I came calling on my search for Othman. The fact that I even found her was itself (depending who I consulted) a combination of sheer luck, divine providence, or the nature of small Iraqi villages.

As I left Wajriah’s in Saqlawiyah, I showed her the few pictures on my phone I had been showing everyone with no success: Othman (whose name I still did not know), Hajjar and her notebook, and Hajjar’s mother Khadija, who has one eye nearly sealed shut, an injury from the fight for Fallujah.

One of Wajriah’s brothers, it turned out, was married to Hajjar, and she passed along a helpful phone number, warm regards, and the comment that her sister-in-law “always was smart.”

And that’s how I re-met Hajjar and ended up rifling through papers with her, and learnt that one of Hajjar’s closest friends in the camp is an aunt of Othman’s who sometimes looks after the boy and his sister. She once took them on a doctor’s visit to help their grandmother navigate the hospital bureaucracy.

Thanks to Hajjar, I now know that Othman is not from Saqlawiyah but from another village north of Fallujah called al-Sejar, which had many men caught up in the same gruesome selection process.

Relying on her memory, not her records, she tells me that Othman has a father, and that he is alive.

That’s because Othman’s father had the strange fortune of being in the process of escaping an IS prison when his house was hit and his family took flight. He was later reunited with the family, then rearrested in the camp for several months, and eventually cleared of ties to IS.

Hajjar tells me all this from a burned out building in Fallujah where the National Geographic channel plays on a small TV set. She says that Othman has gone home, and I will find him there. And I did, helped by the names she provided, but not the phone numbers – they had all been shut off.

Despite pointing me in Othman’s direction, and having herself travelled to seemingly every corner of Iraq for answers, home is the one place Hajjar won’t go.

“If I went there I would cry forever. It’s only women, no men.”

807 blue folders

The village they say has no men is still run by men, who say they are powerless in the face of so much need.

At the modest Saqlawiyah local council building, members sit on maroon pleather chairs smoking cigarettes and sweet tea.

Mustachioed council head Ismail Obaid recounts the village’s story, but emphasises his information is second-hand: the council was in exile when the army and militias came and the remaining men were taken.

He knows women in the village are suffering and that some have even gone back to the camps because at least they have guaranteed rations there, but he says there’s not much he can do. Some charities are pitching in with food, but he says it’s not enough. “These families are only surviving with the help of God,” he says plainly. “We don’t give them anything, we don’t have the funds.”

The government has promised compensation for all Iraqis whose homes were damaged and destroyed, as well as cash for each returning family, but with so much of the country in ruins, the process is achingly slow.

Sattar Newrouz, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Migration and Displacement, says the ministry has not been able to make all the payouts it promised “because of the economic crisis and lack of budget” for his ministry.

“These families are only surviving with the help of God. We don’t give them anything, we don’t have the funds.”

He says the government is working through individual compensation claims, and that despite a cash shortage, he believes “the government has the intention to compensate these families to rebuild their homes.”

But for families with missing loved ones, answers are as important as money (although that would help too). At the Saqlawiyah local council there is a pile of light blue folders, one missing person’s complaint for each man.

The folders contain all the legal niceties required to fill in a claim like this in Iraq: ads placed in the papers listing a man’s name, date of birth, and so on; receipts from the papers; letters from a judge certifying that the ads were placed. The complaints also require an accused. In this case, each one is addressed to “unknown”.

If the missing men of Saqlwawiyah were employed in the public sector – like 40 percent of Iraq’s workforce – these claims should ensure their wives receive their salaries. But it’s a rural area and most people were farmers, construction workers, or had other informal employment.

Hajjar thinks the blue folders are useless anyway. She says the local council lost her husband’s file twice and now she just keeps a copy at home with her other records.

Various committees have been formed to investigate the fate of the men, and the government has promised accountability. But Obaid, who is a member of a tribal council established to investigate just what happened in early June 2016, says they have visited various high-ranking political and security officials, including those in the Hashd militias.

“We haven’t got anything from them,” he says. “They were not responsive.”

He says the Ministry of Social Affairs also promised to pay families the sort of salaries public employees get. “But no salaries were received, only promises,” says Obaid.

Now that parties representing the Hashd militias put on a strong showing in the May elections – coming in second for votes after a coalition led by Shia cleric Moqtada al-Sadr – the prospect anyone will claim responsibility for the events at Saqlawiyah seems to be fading.

Before I leave the local council, I pass around the photos of Othman and the women – I haven’t yet talked to Wajriah and Hajjar, and I am still searching. A member of the council who is also a paediatrician zooms in on Othman’s wounds.

He doesn’t recognise Othman, but he takes a sharp breath in. “Most of them are shells,” he says, pointing to the boy’s wounds on the screen. “These are burns.”

The doctor says he has been among those who attended to the luckier men of Saqlawiyah, those released after they were tortured.

“To be honest, this is not too [bad], compared to what I have seen.”

Return to the village with no men

Almost everyone from Saqlawiyah and al-Sejar have now left the camps where many were staying, along with 3.8 million other Iraqis who have returned.

But with so many missing men – not only loved ones but also breadwinners in rural parts of the country where it is rare for women to work – homecoming has not been a panacea.

Hajjar, in her parents’ burned out home in Fallujah, has heard what happened to her two-bedroom house in Saqlawiyah, and it’s not good. “Life is very hard without a husband,” she says from Fallujah. “We came back to nothing. We lost our car, our home, our money, the furniture, everything.”

Even though it defies convention, at 40 years old, she’s looking for her first job.

Wajriah, in her borrowed house in Saqlawiyah, has no source of income for her large family. “We don’t have salaries, we don’t have any money,” she says. “We only have good people who donate food and clothes for the kids.”

She does have a kindly neighbour with white hair who comes over and helps out when he can, who sat quietly when I came by.

Othman returns home

It’s so bad for the women of Saqlawiyah that some have even turned around and gone back to the camps, where they have guaranteed food and water. One elderly woman I met between the tents in the camp where Othman once lived, Salima Mahmoud Talal, was looking after four grandchildren. Going home wasn’t even on her mind – her relatives had told her it wasn’t worth the trip.

“All of our men were taken,” she said. “We don’t have any men left in our village… we’re scared to go back home. Half of our homes were destroyed, and the other half were looted. We all have the same stories.”

July 2017

Mosul liberated

1 million newly displaced

Othman’s family went back to al-Sejar in January 2017, although he and his sister first spent some time in Baghdad being treated by a paediatric surgeon who remembers them because they travelled so far for his help and never came back.

Othman’s grandmother Hadoud says her family, like so many others, had to start from zero when they got home. She’s three million Iraqi dinars, around $2,500, in the red for Othman and Deena’s medical expenses alone.

“We have no salaries. No support. I don’t have any money. Every time we have to take the kids to the doctor I borrow money.”

At home with Othman

The way to Othman’s house goes through a checkpoint manned by both militiamen and soldiers, next to a commercial strip covered in holes from heavy machine-gun fire where the corrugated metal doors have mostly been ripped off.

The family has a big tan house with purple trim and a lone cow outside. They managed to pull together enough money to partially renovate the room that was hit back in 2016, because it still smelled like death. But there wasn’t even enough to completely fix the damage in that room: Hadoud pulls aside a plaid blanket hanging on one wall to reveal chunks missing from the charred surface.

Othman was hard to find, but the truth is he wasn’t lost.

He has a father – a loving, smiley one called Rafeh – a grandmother, cousins, aunts, and uncles. He has a sister who would be called an Irish twin somewhere else: now they share face and body scars as well as a birth year.

In some ways, his fate makes him lucky. In others, it makes him typical.

Half of the Iraqis forced from their homes in the past few years are children, including Deena, Hamzeh, Nabaa, and Marwan.

They are the lucky ones: 270 Iraqi kids were killed in 2017 alone. If that doesn’t sound like much, it’s likely because the UN can’t count all the deaths from conflict, let alone those who died because they didn’t have adequate medical care or food under siege. There may even be bodies still underneath the collapsed buildings in places like Mosul, which has only been free of IS for one year. Its Old City, at least, is still a pile of rubble.

December 2017

Iraq declares victory

over IS

Of those still alive, many have lost parents, siblings, and friends. They will have to make up for years of lost school, and eventually find jobs in an economy that is flagging, and where many of the country’s best and brightest do their best to leave.

For young people who suffered at the hands the Hashd or other groups – Shia militias are hardly the only groups accused of war crimes in the past few years, though IS killed the most of all – and continue to feel neglected by the state, it will take reconciliation, education, and serious investment if they are to grow up believing all Iraqis are their brothers, regardless if they are called Othman or Ali.

Othman’s future likely holds many more doctors’ visits to have more shrapnel removed – Hadoud says she’ll borrow more money to take Othman and his sister back to the specialist in Baghdad. The doctor says he’ll be waiting.

In some ways, his fate makes him lucky. In others, it makes him typical.

Othman and Deena will start school in a year, which may pose a problem because sitting in the family’s house, Othman still doesn’t talk, at least not to strangers. He isn’t tempted into playing with the red football I brought as an offering (although he does hold it tight), but he does silently consume his fair share of chocolates while he cuddles up to Hadoud.

May 2018

Iraq holds elections

Rafeh and Hadoud say he’s especially shy around strangers, having been handled by so many doctors and aid workers in the past few years. When I ask what he talks about, they say that the day before he asked for a shovel to dig up his mom and bring her home.

We walk through the house, examining the damage to the room where Othman and Deena were injured.

Othman lingers for a while, looking out the window into a different room, one piled high with mattresses, blankets, and pillows the large family takes down at night. His fingers touch the ledge. Deena comes to join him for a moment, and then lets him alone again. Othman doesn’t tell me, but maybe he doesn’t have to; this room had been his mom’s.

as/ag/js

Our forthcoming reporting on Iraq will explore humanitarian funding, post-conflict justice, and the barriers some people face as they attempt to return home.