Attempts to contain the world’s second deadliest Ebola outbreak ever hinge on the successful deployment of an experimental vaccine that has already proved a game-changer in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

This time around, however, success is far from certain. Cases have spiked in recent months – passing 2,000 on Sunday – and now the response has to balance vaccinating an increasingly large number of people with a stock of vaccine that is not endless.

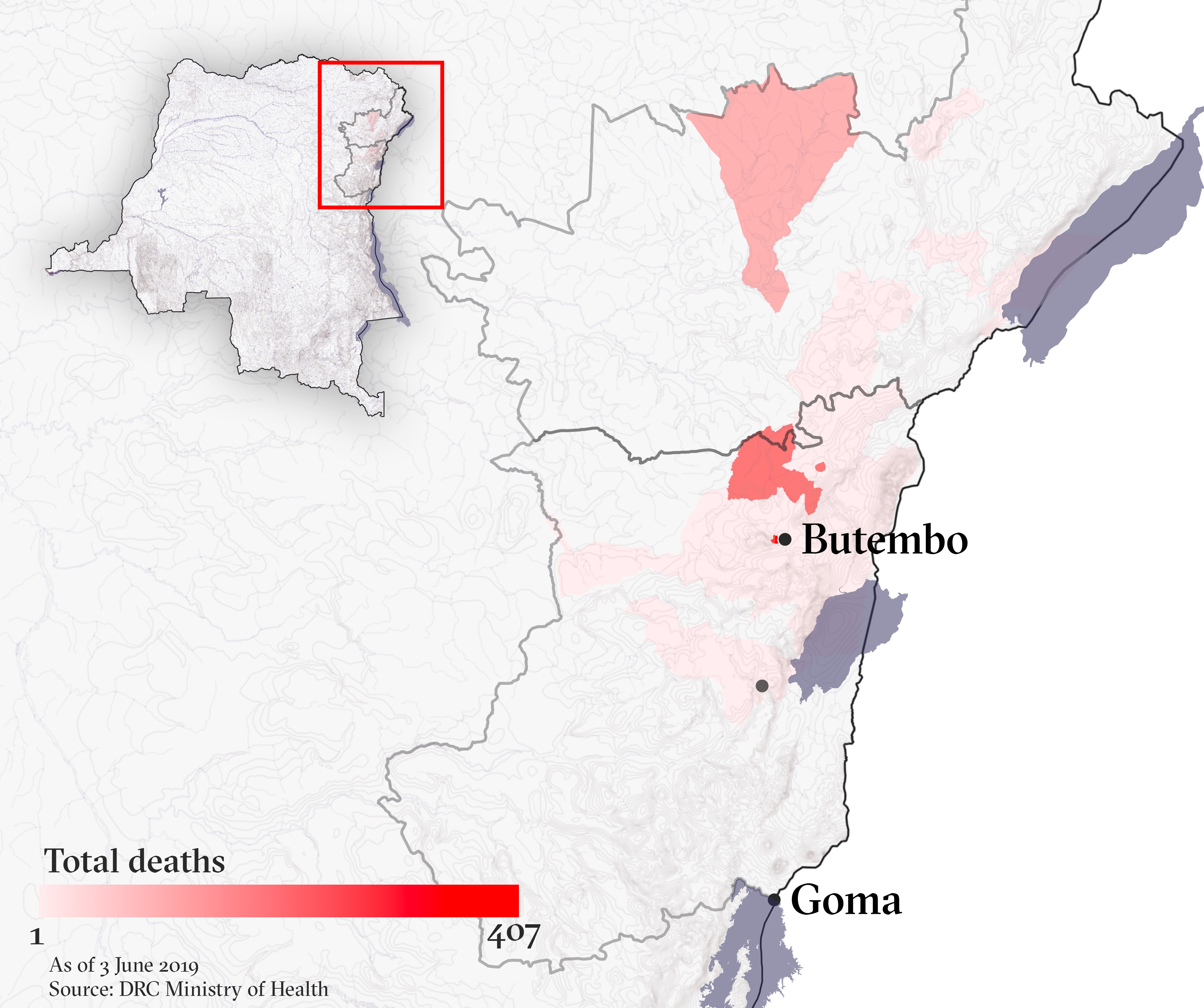

At least 1,346 people have died, and the longer the epidemic continues the greater risk it could spread to major cities like the North Kivu provincial capital, Goma, or across the eastern region’s porous borders.

Read more → As Ebola cases rise, so do worries of a cross-border epidemic

This briefing explores the vaccine, the strategy the Congolese government and the World Health Organisation have adopted, and the problems confronting health workers as they respond to the first Ebola outbreak in an active conflict zone.

Has the vaccine worked in the past?

Merck’s V920, or rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP, received a successful Phase III trial towards the latter stages of the 2013-2016 West Africa epidemic that killed more than 11,000 people across Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone – by far the deadliest outbreak of Ebola to date.

It was first used in the early stages of an epidemic during last year’s outbreak in Congo’s northwestern Equateur province. It helped contain the virus and bring the epidemic to a halt in under three months, with only 33 lives lost.

Read more → A short history of the Ebola vaccine

Still unlicensed, the vaccine was deployed on “compassionate use” grounds soon after the current outbreak was officially declared in August last year. Again, V920 has proved highly effective, delivering close to 100 percent protection for the more than 129,000 people vaccinated in time in the affected eastern provinces of North Kivu and Ituri.

What is the vaccination strategy?

At the start of the campaign, the plan was to follow the same “ring vaccination” strategy that had proved successful in Equateur.

All known “contacts” of those suspected of having contracted Ebola are the first to be offered vaccinations. Next are the contacts of those contacts, along with anybody considered at particularly high risk, such as frontline healthcare workers. By forming a “ring” of immunity around a confirmed case, the disease is less likely to spread.

To be effective, this strategy requires investigating every single case of Ebola to identify each person who might have been in contact with them – a time-consuming system known as “contact tracing”.

Responders also keep an eye on contacts of an Ebola patient and follow them for the incubation period of the virus – up to 21 days. This allows those most likely to become new cases to be checked for symptoms so they can be isolated and treated quickly.

What are the challenges?

According to the WHO, more than 90 percent of people consent to vaccination. The main issues are therefore reaching people safely and, as the campaign expands to try to cover more people, ensuring there is enough vaccine.

Two large and interconnected challenges are preventing the campaign from reaching everyone it needs to: deep local distrust of the Congolese government and Ebola responders; and grave insecurity that has seen more than 170 attacks on treatment centres and healthcare workers since January. The situation has been made worse by some inaccurate or deliberately misleading information, propagated largely on social media.

“We have a vaccine, but the ring strategy involves identifying contacts of the case and the contacts of the contacts, so this requires the cooperation of the community.”

The targeted vaccination has caused some confusion in certain communities, where people see some members getting vaccinated – generally the contacts of a confirmed or suspected case – but not others.

“We have a vaccine, but the ring strategy involves identifying contacts of the case and the contacts of the contacts, so this requires the cooperation of the community,” said Dr. Ray Arthur, head of the Global Disease Detection Operations Center at the US Centers for Disease Control. “If contacts can’t be seen, if they don’t want to be followed, if they flee, if they don’t get into a setting where they can’t infect others, transmission continues.”

Attacks on Ebola treatment centres and healthcare workers in recent months have claimed at least four lives. Those leading the response say it has been the large-scale attacks on or near the affected towns of Butembo and Katwa – and subsequent suspensions of operations – that have derailed the vaccination campaign most.

How has the strategy changed?

After cases spiked at the end of April, the WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts, or SAGE, issued new recommendations on 7 May that amounted to an overhaul of the strategy.

Read more → WHO overhauls vaccination strategy as Ebola cases surge

“SAGE expressed grave concern about the current worsening outbreak epidemiology and completeness of ring vaccination, noting that disease transmission continues to occur notably in locations where ring vaccination cannot be implemented and that a large proportion of new cases continue to arise among unknown contacts,” the panel said.

As a result, the experts proposed a raft of new measures aimed at combatting the insecurity and distrust. These included ramping up “pop-up” vaccinations at protected vaccination sites and geographically targeted campaigns to vaccinate entire villages or areas. They also recommended extended vaccinations to a third ring: contacts of contacts of contacts.

After SAGE called for a “mass communication campaign” to build back trust, the WHO announced it would work to ensure that by the end of May “a majority of vaccination team members are healthcare workers, doctors and medical students from affected communities who also speak the local languages.”

Will more vaccine be needed?

The new guidelines require many more people to be vaccinated and this has clear implications for stocks of the vaccine.

To address the risk of vaccine shortage, another SAGE recommendation was to cut doses from the current 1ml to 0.5ml for first- and second-level contacts, and down to 0.2ml for the third-level contacts.

“It’s difficult enough today to vaccinate some of those communities that are very suspicious.”

SAGE noted that dose reduction “is associated with potential risk of reduced vaccine effectiveness.” But it stressed that the 0.5ml dosage would be effective as this was the amount administered in the vaccine trials conducted in Guinea in 2015. It did say that developing immunity might take up to 28 days for those vaccinated with the 0.2ml dose.

Although the new measures will ensure the new vaccine stock lasts longer, it could make it harder to vaccinate those at risk.

“It’s difficult enough today to vaccinate some of those communities that are very suspicious,” said Natalie Roberts, a physician and manager of the Ebola crisis emergency desk at Médecins Sans Frontières.

“If you’re then trying to explain to communities: ‘some of you will get the full dose, some of you will get half dose, some of you will get one fifth of the dose’… the difficulties in communicating that… are very complex,” she warned. “It could all backfire.”

Could the vaccine stock run out?

In short: probably not, but it depends how fully the new strategy is implemented and how much vaccine is produced in the next few months.

SAGE said its dose reduction recommendations were “to ensure vaccine continues to be available and offered to individuals at greatest risk of Ebola during this outbreak and in order to secure the availability of the rVSV ZEBOV-GP in the mid-term.”

“A potential vaccine shortage may manifest in case the outbreak expands further and/or is prolonged,” it also noted.

In mid-May, the stock held in Congo was only around 5,210 doses, according to the Congolese Ministry of Health. But most doses are held outside the country where it is easier to maintain them.

Merck said it had 195,000 vaccine doses of 1ml in stock abroad and expected to have an additional 100,000 doses available in July.

Merck says it takes a year to manufacture a full batch of V920, but would not be drawn on when it might be able to produce another batch after the July delivery.

"We continue to manufacture doses and we are working closely with the World Health Organisation and US Government groups to determine when the next batches will be produced,” a Merck spokesperson said by email. “Any updates will be disclosed at the appropriate time."

Julien Potet, a policy advisor at MSF, said Merck had encountered issues with its new factory in Germany and it won’t be fully operational anytime soon. As a result, Potet said, “we have enough doses [but only] if we do a very targeted vaccination.”

Merck confirmed that doses were made in smaller labs for the time-being and that snags with the opening of the larger factory were still being worked out.

How might needs grow under the new strategy?

According to an April WHO report, about 69 people are vaccinated for each Ebola case. Adding a third ring of vaccination would add 50-100 cases, based on a WHO estimate. It could be many more if geographical vaccination is used. But on a cautious assumption that 80 people per Ebola contact are vaccinated at the third ring – that’s a total of 149 vaccinations per Ebola case.

Using the current average of 18.5 cases per day, that’s 82,695 vaccinations every month – but only as long as the outbreak doesn’t accelerate. Based on the current stock and using a full 1ml dosage, Merck’s stock would run out in under four months.

Are there alternatives to Merck’s V920?

More than a dozen vaccines against Ebola have been developed since Ebola was first discovered in 1976, but Merck's V920 is the only one being used in the current epidemic, according to the Congolese Ministry of Health.

Last month, SAGE recommended adding another vaccine to the mix – Johnson & Johnson’s Ad26.ZEBOV/MVA-BN-Filo.

The stock of this vaccine is large, 1.5 million doses, but there is less evidence of its efficacy than V920 as it is still undergoing Phase III trial. So far the Congolese Ministry of Health has appeared reluctant to use it, expressing concerns about the confusion the additional vaccine might sow amongst local communities. It also says it hasn’t yet received a request from the WHO to use it.

The J&J vaccine differs from V920 in that it requires two injections a couple of months apart. Those two jabs are expected to provide longer-lasting protection against Ebola, but at the potential cost of taking longer to reach full immunity.

Nevertheless, the J&J vaccine has the advantage of using a combination of four different strains of Ebola, making it more likely to be effective in other epidemic outbreaks compared to the Merck vaccine, which is based on a single strain.

Both vaccines need to be stored in sub-freezing temperatures to last more than six months, a significant hurdle in places like eastern Congo where electricity is absent or unreliable.

(TOP PHOTO: An MSF staff member prepares a dose of the rVSV-EBOV experimental vaccine at a clinic in Guinea in 2015.)

ef-te/oa/pd/ag