Caribbean governments want to be “taken seriously” in humanitarian management, and this year’s hurricane crises are an opportunity for the UN to “let go”, says a senior regional official. The Caribbean is dealing with “something we’ve never experienced before” but proudly coping, Ronald Jackson, head of the 18-member Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency, told IRIN, adding that CDEMA effectively playing a leadership role is a “glimpse of the future”.

At times, sharing and assigning responsibilities has been tricky in the rolling crises caused by recent hurricanes Irma, Jose, and Maria: Several sources close to the Caribbean operations had told IRIN of a tense relationship between CDEMA and parts of the deployed UN teams.

But Jackson, speaking to IRIN from the CDEMA office in Barbados, brushed such talk aside. He said CDEMA would play its mandated role at the forefront of the response and looked forward to a “posture of support” from the UN humanitarian system, which didn’t mean the UN should “disappear". Referring to UN assistance in the past, he added: “you've held our hand while we crawled”, but now “we're walking”.

Tough road ahead

“You've held our hand while we crawled but now we're walking”

The scale of the challenge is illustrated by looking at hard-hit Dominica, where initial assessments suggest most of the 73,000 population are likely to need assistance after Hurricane Maria devastated agriculture, housing, and public services.

The population is “shell-shocked”, according to Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit, and the island’s infrastructure trashed. Public order is fragile but improving after extensive looting. Water, power, and telecommunications are gradually coming back and roads getting cleared.

Ships, personnel, and aircraft, and dozens of international aid teams have descended on the Dominican capital, Roseau. The flow of incoming cargo deliveries by air and sea, combined with ongoing distributions and services around the mountainous island nation, demands coordination and close management.

Up to the task?

The UN’s top official for Dominica, Stephen O’Malley, told IRIN that CDEMA’s mandate is “very clear” and it enjoyed the confidence of the UN and international donors. He said “bumps and bruises” were to be expected in a fast-paced and pressurised work environment but there was no reason to consider a radical change to the coordination setup.

Aid groups are “cracking on”, he said, noting that CDEMA was integrating UN strengths in fields such as health, logistics, and shelter. While institutional relationships may take time to settle, O’Malley, who visited Dominica on Wednesday to bolster the UN’s support to the government and CDEMA after an appeal at UN headquarters by Prime Minister Skerrit, said there had been an “outpouring of solidarity” from neighbouring countries and the diaspora.

Barnaby Willitts-King, senior research fellow at the Humanitarian Policy Group, said this year’s hurricane response – with CDEMA effectively taking the lead – may prove a turning point in disaster response in the region. He also noted that some 30 other regional humanitarian bodies around the world similar to CDEMA can also struggle to find the resources and space to prove themselves.

CDEMA has worked alongside UN-led mechanisms for years and has enjoyed extended donor support. It is stretched like never before but has reached a stage where it can handle 2017’s crises, O’Malley argued.

Jackson said CDEMA’s budget planned for three crises in the year, but that September had more or less sapped the whole year’s planned expenditure. With a core team of 21 and an emergency operations budget of only about $1.5 million, new funding was needed, he said. CDEMA has played a leading role on several islands this year. Arthurs himself had been providing support in the British Virgin Islands. Overall, hundreds of civilian, police and military personnel have been deployed under CDEMA’s coordination.

Growing regional self-reliance

In some regions there is discomfort about the UN coming in and taking over, and an increasing resistance to any overbearing, “boots-on-the-ground” manifestation of the UN system, Willitts-King told IRIN. Another part of the ”burden of coordination” for CDEMA, he said, would be handling the flood of aid groups “bundling in” and “looking for profile”.

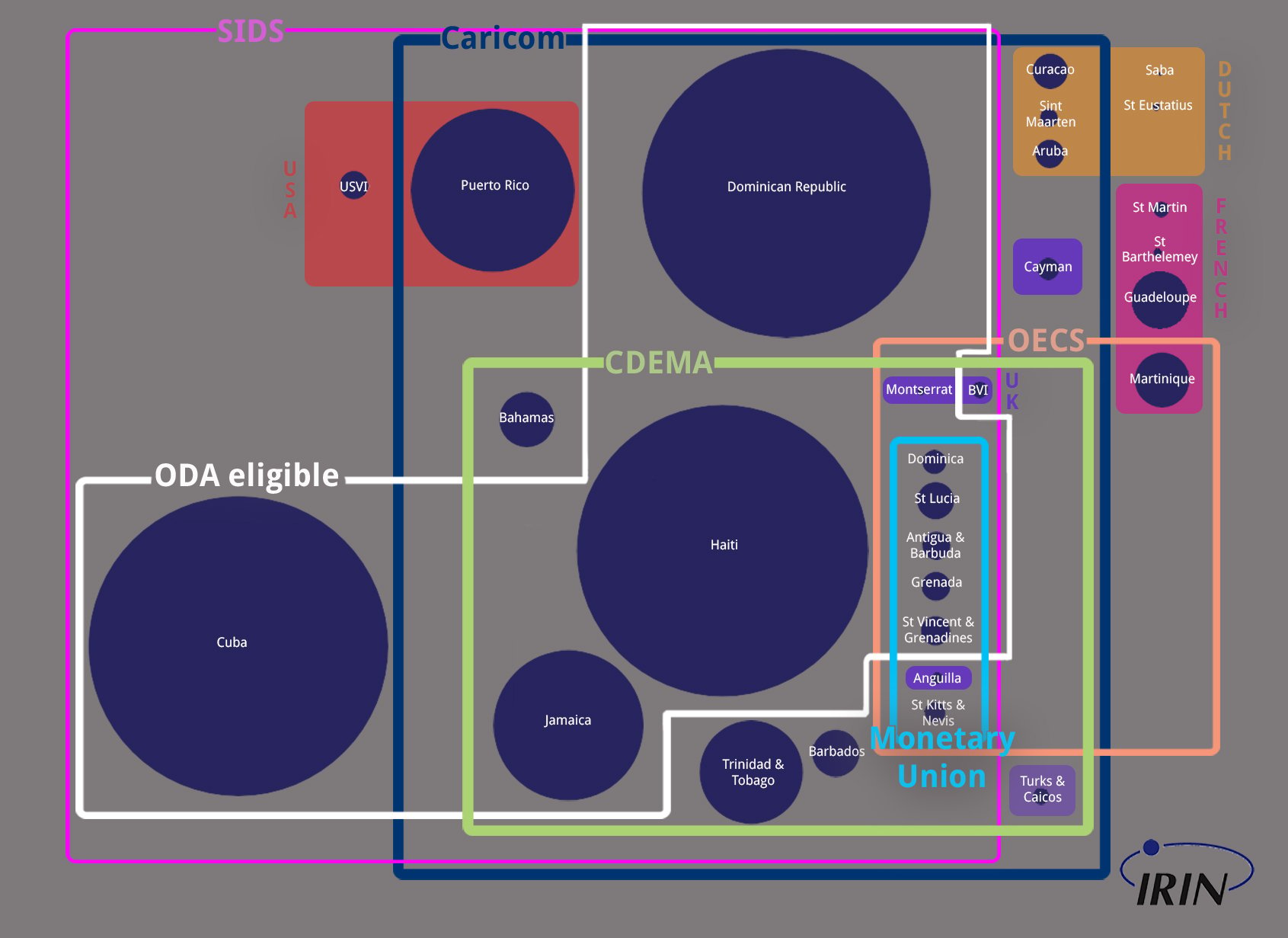

Click here for larger image or read more about the diagram here

More assertive national and regional coordination may be the trend: After Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, the Filipino government resolved, next time, not to allow “the international road show”, Willitts-King said. The need to support regional disaster bodies was recognised at the World Humanitarian Summit, Willits-King said. A report he co-authored in 2016 found “a new wave of thinking on how regional organisations can more fully contribute to humanitarian action, either alongside or in lieu of the international community”.

One senior aid worker warned against a “big beast” of orthodox UN coordination for such a small country as Dominica and welcomed the CDEMA setup, even if there had been teething troubles.

Jackson said his institution and region was “desirous of being recognised” for its emergency response, but looked forward to handing off to the UN and other institutions in the recovery and reconstruction phase. Despite the tragedies of the crisis, he said he was “energised” and the relief effort was about “expressing capabilities” and “freeing up the potential of the region”.

bp/ag