A scar still runs down my right hand from when a schoolmate stabbed me in 1995 as I slept in a dormitory. He was a Tutsi whose brothers had been killed a few years earlier. In his grief, he blamed me, a Hutu. I owe my life to a blanket that was just thick enough to absorb that blade.

Yes, Burundi is a troubled place. The discovery of thousands of mass graves over the past year and a half makes that clear – especially in a tiny country of only a few million people.

The graves contain the victims of mass killings that have scarred my country for decades. As in neighbouring Rwanda, most died because of their ethnic background – either Hutu or Tutsi – though the killings here have received less attention.

Now, gravediggers in jumpsuits and gumboots are picking through the remains, hoping to finally identify the dead and establish the circumstances in which these badly documented and poorly recognised genocide crimes took place.

Hear from the author about why he wrote this piece.

The efforts are being led by a truth and reconciliation commission, like the one set up in South Africa after the end of apartheid. The idea for ours was conceived in 2000 as part of a peace deal brokered by Nelson Mandela, though it took a long time for work to commence.

Since January 2020, I’ve been following the commission, visiting graves and documenting atrocities around the country. I have seen some remarkable things: family members identifying the remains of their loved ones after decades of searching; killers asking victims for forgiveness.

But while the commission is shining some much-needed light on the past, old wounds are also being reopened. The process, some believe, is deepening divisions rather than helping us heal.

The commission is mandated to investigate atrocities dating from the 19th century, when Burundi was first colonised by a European power, to 2008, when the last active rebel group here signed a ceasefire with the government.

Critics say this timeframe ignores crimes committed since 2015. That was the year our deceased former president, Pierre Nkurunziza, won a controversial third term in office, triggering protests, a crackdown, and the displacement of some 400,000 Burundians.

Others say search teams are focusing on Hutu rather than Tutsi victims, particularly Hutus who died in a 1972 genocide. The commission denies being biased, but its close links to our ruling party – a former Hutu rebel group – mean some question its motives.

One thing is clear: We have all been affected by war. As the scholar of Burundi, René Lemarchand, once wrote: “Nowhere else in Africa have human rights been violated on a more massive scale, and with more brutal consistency, than in Burundi.”

That attempt on my life in 1995 was not my only brush with death. In 1996, Tutsi soldiers stopped me and my friends by the side of the road, claiming we were Hutu rebels. They made us lie down with two metres between us. An armoured truck then edged forward, crushing my friends to death, one by one.

I survived thanks to a local Tutsi man – François Mbesherubusa – who was passing by. He knew my father and told the soldiers: “Désiré is like my son; you must release him.” My friends Bigirimana, Yohani, and Gerard were not so lucky. Their deaths still haunt me after 25 years.

Mbesherubusa passed away some years ago, but my family has stayed in touch with his. After his death, I brought clothes to his wife as a gesture of my gratitude. And I work today alongside his daughter for a business cooperative that aims to combat rural poverty in southern Burundi.

Hear the author speak about his father, a survivor of the 1972 genocide.

Confessions of an accomplice: ‘I was used. And I obeyed to remain alive.’

Much has changed in recent years. A peace agreement in 2000 – and subsequent accords with rebel groups – helped establish a Hutu-Tutsi power-sharing arrangement that has eased ethnic conflict.

But so far there hasn’t been any real accountability, or any meaningful engagement with our country’s past – an oversight the Truth and Reconciliation Commission now seeks to correct.

Provisions for transitional justice in Burundi were included in the 2000 Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement, which helped end the civil war that broke out in 1993. The accord called for the establishment of a criminal tribunal as well as a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

The tribunal is yet to be established, however, and the TRC took more than 14 years to be set up. One reason for the delay was that the government prioritised peace negotiations with holdout rebel groups over transitional justice.

Disagreements over the different mechanisms also broke out between Burundian authorities and the UN, which had a heavy influence in the country after the civil war. And the vested interests of various political elites played a role too.

“As many of them have blood-stained hands, their interests converge in having as little truth and accountability as possible,” Stef Vandeginste, a Burundi specialist at the University of Antwerp, wrote in a 2012 academic paper.

The law for the TRC was eventually passed in 2014 with resistance from opposition groups that criticised the absence of a judicial mechanism, and that felt the commission would be controlled by the ruling CNDD-FDD – itself a party during the civil war.

The TRC’s original mandate lasted four years and covered crimes committed since independence in 1962. But the mandate was extended in 2018 and expanded to cover the entire colonial period – a move critics said would stretch the commission’s resources.

The TRC formally began work in March 2016 – a year after presidential elections saw late president Nkurunziza win a controversial third term in office. Civil society activists said the timing was designed to divert attention away from the electoral crisis.

“A solution to the ongoing political crisis would ideally be needed before the TRC begins its difficult task of uncovering painful – and highly politicised – memories of the past,” stated a 2016 report by Impunity Watch, a human rights organisation based in the Netherlands.

Finally set up in 2014, the commission began a nationwide campaign of mapping and exhuming graves last year at a sensitive moment: New presidential polls were being held even as the COVID-19 pandemic wormed its way into the country.

I started shadowing the commission’s workers in Karuzi and Gitega, two provinces in central Burundi. It took me two and a half hours to drive to my first destination from Bujumbura, my hometown and the country's largest city. The rain poured down on rolling hills.

Many people lost their lives in these provinces during the killings of 1972 – the worst Burundi has ever experienced. We call the events Ikiza, which means scourge or calamity in our local language, Kirundi.

Mainstream scholars say the conflict began when Hutus – the majority ethnic group here – launched an abortive uprising against the government, which was controlled by elites from the minority Tutsi population. Around 3,000 Tutsis were killed.

Led by an army officer called Michel Micombero, the government and the all-Tutsi military responded with inconceivable brutality, killing between 100,000-300,000 Hutus in what many consider a genocide.

I was born six years after the bloodshed, but it has shaped my life, as it has so many others. My parents named me Nimubona – which means "only God will protect him" – out of fear for my life if the carnage restarted.

I learned about what happened from my grandparents, who lost relatives and friends. I saw my first grave at the age of seven, when engineers unearthed remains while building a road that passed by my house. Among a jumble of bones was a rusty wristwatch that belonged to my father’s close friend, Aaron, who was arrested and disappeared in 1972.

Still, nothing prepared me for what I saw and heard last year when teams of gravediggers uncovered dozens of mass graves in central Burundi containing the bodies of thousands of people who had died in 1972.

The graves had been found on the banks of a river, beneath banana and avocado trees that commission experts think were planted to conceal the truth. I wondered whether local residents had eaten from them unknowingly.

Bones from different sites had been gathered from the pits and displayed in large piles in canopy tents. The scale was staggering, as were the stories from witnesses I interviewed to try to understand what had happened.

In Karuzi, I met Maximilien Barampama, a local man who was incarcerated at a prison in Gitega for petty theft when massacres began in the two provinces. Soldiers forced him to help carry out the killings. “I was used,” he told me. “And I obeyed to remain alive.”

Hear the author speak about Father Michel Kayoya, a victim of the 1972 genocide.

Barampama explained that Hutus considered educated had been targeted. It was the same across the country: Businessmen and civil servants died in the thousands, alongside pastors, teachers, and students – some still at primary school.

In Gitega, the victims were brought to a local prison, where they slept in squalid cells with no bathrooms. Then they were loaded onto trucks and driven to deep pits dug by bulldozers.

Among them was a well-known Hutu priest, writer, and philosopher, Father Michel Kayoya. Despite atrocious conditions in prison, Barampama and others told me that Kayoya sang gospel songs and invited people to pray alongside him.

Even on his way to the execution site Kayoya kept praying and chanting hymns, Barampama told me. “We are going to father’s house,” he recalled the priest singing, over and over.

Before Kayoya was executed, the priest absolved the sins of his fellow clergymen and clergywomen, Barampama said, and removed a stole he considered too holy to be buried. Soldiers shed tears even as they shot him dead.

During an exhumation in Gitega, glasses that looked like Kayoya’s were discovered, alongside rosary beads and other liturgical clothes. I watched as local residents and religious figures turned up to pay their respects.

The genocidaires' focus on educated Hutus led scholars like Lemarchand to describe the events of 1972 as a “selective” or “partial” genocide: The goal was to create a Hutu underclass and solidify Tutsi control over a one-party state for decades to come.

The cruelty of that mission – which succeeded – had left its mark on Barampama: He was released from prison in 1973 when his sentence ended, but nearly five decades on the trauma was still etched on his face.

A search for loved ones: ‘I feel sorrow for the death of my father, but joy at finally seeing his remains.’

There is no longer war in Burundi, but problems persist. Poverty is widespread, land tensions are common, and rebel groups are still active across the border in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, where everyone in this region tends to dump their problems.

Things have worsened since 2015: The space for civil society and independent media has shrunk, while international criticism has pushed the government into isolationism. Our new president, Évariste Ndayishimiye, has been praised for freeing journalists and renewing diplomatic ties in his first year in office – but there is much still to be done.

Our issues rarely get mentioned by foreign media, and our needs rarely get met by humanitarian groups. According to the Norwegian Refugee Council, an international aid organisation, Burundi is currently the third most neglected crisis in the world.

Our past is neglected too. Unlike the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in neighbouring Rwanda – a country whose history is interwoven with ours – the tragedy of 1972 played out with little attention at the time, and has got even less since.

It is what the government in 1972 always wanted: They blocked journalists who tried to investigate the killings, and they prevented people from mourning the dead in the years of state-enforced silence that followed.

Burundians I spoke with want more from the commission than simply chronicling the bloodshed, though: Most have lost family members during the killings and were hoping the exhumations would bring personal closure.

Every day, crowds would gather at the graves in the different places I visited, watching exhumations unfold behind crime scene tape, while commission workers interviewed those willing to talk.

To identify bodies, the search teams weren’t taking DNA samples: Instead, they held up belts, shoes, clothes, and other items pulled from the ground in the hope that residents would recognise who they belonged to.

Sometimes it worked. In Karuzi, I met Laetitia – she didn’t give her surname. She had followed an exhumation for 10 days, hoping to find her father. Finally, search teams pulled out black sandals and a skull with dental implants that identified him.

As per Burundian culture, confirming her father’s death meant a formal mourning ceremony could finally be arranged. “I feel sorrow for the death of my father, but joy at finally seeing his remains,” Laetitia told me as we cried together.

Rights groups have criticised the commission for failing to follow forensic standards, and for not storing remains in a dignified way. But the Burundians who comprise these search teams have their own powerful personal stories that highlight what’s at stake.

“I just want to be the first to see my grandfather’s remains.”

For example, in September 2020, I met Jean Marie, a young man who was patiently exhuming a grave in southern Burundi’s Makamba province, where I was born. He told me the events of 1972 had trapped his family in decades of hardship.

His grandfather – the main breadwinner – was killed during the massacres, and his father was able to escape abroad to a refugee camp. The family returned to Burundi years later, too impoverished to put Jean Marie through school.

Joining the commission was no accidental job for the young man: He said he was actively searching for his grandfather, who wore a red coat on the day he disappeared, according to witnesses.

Shovel in hand, Jean Marie’s heart would skip a beat every time a dash of red appeared in the dirt. “Here, I am not looking for money,” he told me. “I just want to be the first to see my grandfather’s remains.”

Fear, resentment, and ‘the desire for revenge’

Ethnic violence never used to be a problem in Burundi. Our rulers were once kings and princes who belonged to a separate royal group known as the Baganwa. Differences in class were less about Hutus and Tutsis – who share the same language and customs – than about the Baganwa and their subjects.

While the two groups had some differences, ethnic identity did not determine social and economic rank. The king’s advisors – the abanyarurimbi – drew from both communities. Hutus, meanwhile, could become Tutsi, and some people even identified as both.

As we broke away from Belgium in 1962, the main power struggles involved rival branches of the royal class – the Bezi and Batare factions – rather than Hutus and Tutsis.

How, then, did centuries of cohesion aided by allegiance to a shared monarchy suddenly dissolve into widespread ethnic violence – a puzzle Lemarchand calls “the Burundi paradox”?

The answer is contested. Though scholars have written books on 1972, Burundians have long seen the history as incomplete, and the commission is now challenging some of the narratives that have emerged.

Still, some factors clearly played a role. A Hutu revolution in Rwanda – beginning in 1959 – against the Tutsi-led monarchy saw hundreds of thousands of Tutsis flee to Burundi, straining relations between the groups. The abolition of our monarchy in 1966, meanwhile, removed a stabilising force and crucial buffer against ethnic strife.

The fault lines hardened after the 1972 genocide. And when Tutsi radicals assassinated our first democratically elected president – a Hutu – in 1993, a civil war broke out between Hutu rebels and the Tutsi-dominated army. By 2005, another 300,000 lives were estimated to have been lost and 1.2 million Burundians displaced.

A small, landlocked nation in Africa’s Great Lakes region, Burundi was first colonised by Germany in 1890. After World War I, the country was ruled by Belgium – first under a League of Nations mandate, then as a UN trust territory.

During the Belgium period, colonial administrators stereotyped Tutsis as a superior race and discriminated against Hutus. Divide and rule policies, meanwhile, targeted the royal Baganwa class, which transcended ethnicity.

After independence in 1962, power struggles broke out between Baganwa groups – the Bezi and Batare. Within a few years, politics had also taken an ethnic turn in a way unparalleled in Burundi’s history.

Several factors account for the rise in ethnic tensions, according to scholars of the period. Events in neighbouring Rwanda – a country so closely interwoven with Burundi that some call them “false twins” – had a major influence.

A Hutu revolution – beginning in 1959 – against Rwanda’s Tutsi-led monarchy flipped the country’s power balance and saw hundreds of thousands of Tutsis flee to Burundi. Their arrival stoked fear among Burundi’s Tutsis that the same fate could befall them.

The assassination in Burundi of prime minister and prince Louis Rwagasore in 1961 sharpened ethnic divisions by removing a popular, unifying figure in the country. The abolition of the monarchy in 1966 removed yet another stabilising force.

A military coup that same year, meanwhile, initiated a period of Tutsi rule that would last for decades. Any challenge to their power by the Hutu majority was met with shocking levels of repression.

In 1972, up to 300,000 Hutus were killed in what many scholars consider a genocide. In 1988, as many as 20,000 more Hutus were massacred following a Hutu uprising sparked in part by rumours of a “new 1972” being planned.

Facing growing international concern, Burundi finally began a process of reform in the early 1990s. A new constitution was adopted as part of a transition to multi-party democracy led by then-president Pierre Buyoya.

Polls in 1993 saw Melchior Ndadaye defeat Buyoya and become Burundi’s first democratically elected president – and first ever Hutu leader. But his stay in power would prove short-lived.

In October 1993, Ndadaye was assassinated by Tutsi military officers – a killing that triggered spontaneous anti-Tutsi violence that UN investigators said constituted “acts of genocide”.

The assassination also set in motion a 15-year civil war between Hutu rebels groups and the Tutsi-dominated army. Another 300,000 lives were estimated to have been lost and 1.2 million Burundians displaced.

A peace agreement brokered by former South African president Nelson Mandela led to the signing of the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement in Tanzania in August 2000. But the accord did not initially include the main rebel groups.

Further ceasefire agreements, however, were signed by the rebel groups, which then transformed into political parties. The leader of one group – Pierre Nkurunziza – became president in 2005.

The Arusha agreement led to an elaborate power-sharing system that helped ease ethnic conflict by ensuring Tutsis and Hutus had fair representation in parliament, the army, and other key institutions.

But political instability continued as Nkurunziza’s party – the CNDD-FDD – sought to cement its power. Nkurunziza won a second term in 2010 – amid an opposition boycott – and a third in 2015 that many considered unconstitutional.

Mass protests against Nkurunziza’s third mandate were followed by a crackdown that saw hundreds of thousands flee abroad. Despite fears of ethnic violence and genocide, the crisis, however, remained largely political.

Presidential polls in May 2020 were marked by outbreaks of violence, but also by a change in the guard: Nkurunziza stepped down for Évariste Ndayishimiye, a CNDD-FDD former army general with reformist credentials.

Ndayishimiye had been due to take over from Nkurunziza in August 2020 after winning the May polls. But the 55-year-old incumbent died suddenly in June 2020 propelling his successor into power a few months earlier than anticipated.

While everyone has suffered during these cycles of violence, civil society groups have accused the commission of bias for allegedly focusing its investigations on the events of 1972, and on the Hutu rather than the Tutsi victims of those killings.

Opposition activists have linked the focus to last year’s elections, claiming the ruling CNDD-FDD party – a former Hutu rebel group that took up arms in the 1990s – was trying to drum up support among the Hutu electorate.

Others suggest the CNDD-FDD has more personal motivations: closure for relatives and friends that party members lost in 1972, and avoiding tough questions that would arise should crimes the ex-rebels committed be investigated too.

The president of the commission, Pierre Claver Ndayicariye, denied any bias when I interviewed him in March 2020. He said the commission had opened various mass graves from the 1990s, and that all atrocities would be investigated in due course.

Asked why the majority of exhumations to date have involved graves from 1972, Ndayicariye told me that witnesses and perpetrators from the war won’t be alive much longer. Families of the missing, he added, have also waited the longest for answers.

On the ground, feelings of resentment against the commission were clear, however. In Makamba province, I met a Tutsi man who wouldn’t provide search teams with the location of a mass grave where his father was buried because he resented the agency.

Several Tutsi community members I spoke with said they also feared violence should their Hutu neighbours conclude they were to blame for what the commission was uncovering – findings that could be used to prosecute perpetrators should the government so decide.

Hear the author speak about Emmanuel Ndahigeze and other heroes of 1972.

The UN’s Independent Commission of Inquiry on Burundi agreed with that assessment. In March 2020, it warned against “the risk of reviving past antagonisms, including the desire for revenge”.

In asking communities to relive the past, the commission’s work has also shown how our memories differ. In Rumonge province – next to Makamba – Hutus I spoke with denied that members of their community had killed Tutsis in the revolt that precedeed the 1972 genocide. Local Tutsis said the opposite.

And while Hutus almost universally see the events of 1972 as an indiscriminate extermination campaign, some Tutsis I spoke with viewed it as a legitimate response from a government trying to combat Hutu insurgents.

With the past contested and mythologised, there were times when I questioned how the commission could fulfil its mandate to separate fact from fiction, let alone help reconcile Burundians around the country.

Torn up hit-lists, and the men who saved my father

But the commission’s work isn’t just fostering division: Over a year of reporting, I have seen many Hutus and Tutsis unite to give information on what happened in 1972 – something that fills me with hope for the future.

The clearest example was in Bururi, a southern province where Hutu insurgents killed many Tutsis in 1972, and where the Tutsi officers behind the subsequent genocide – sometimes dubbed the “Bururi mafia” – were born.

Residents said rivers in parts of the province turned red as Hutu victims were tossed into the water. Commission workers told me 18,000 people likely died here, with many mass graves yet to be discovered.

While some Bururi locals refused to help the commission, one group of local Tutsis volunteered details that led to the discovery of a mass grave containing the bodies of 121 Hutu secondary school pupils – future elites in the eyes of their killers.

The commission was able to identify the names of the pupils – buried in the middle of a forest – using archived photos and files smuggled out of the school in 1972 by a Tutsi teacher who had defied official requests that they be destroyed.

Similar stories of solidarity emerged wherever I went. In another Bururi commune, I learned about a Tutsi teacher who had refused to hand over his Hutu students to the military, and who died alongside them as a result.

In the northern province of Kirundo, I met the daughter of a Tutsi army corporal – Emmanuel Ndahigeze – killed for the crime of feeding Hutu prisoners. And in Makamba, Hutu residents told me about a Tutsi pastor who challenged soldiers carrying a list of Hutus to be killed in 1972.

“When he heard that there was a list, he searched for it,” Protais Ndayizeye, a local resident told me. “When he got it, he tore it into pieces, and some lives were saved like that.”

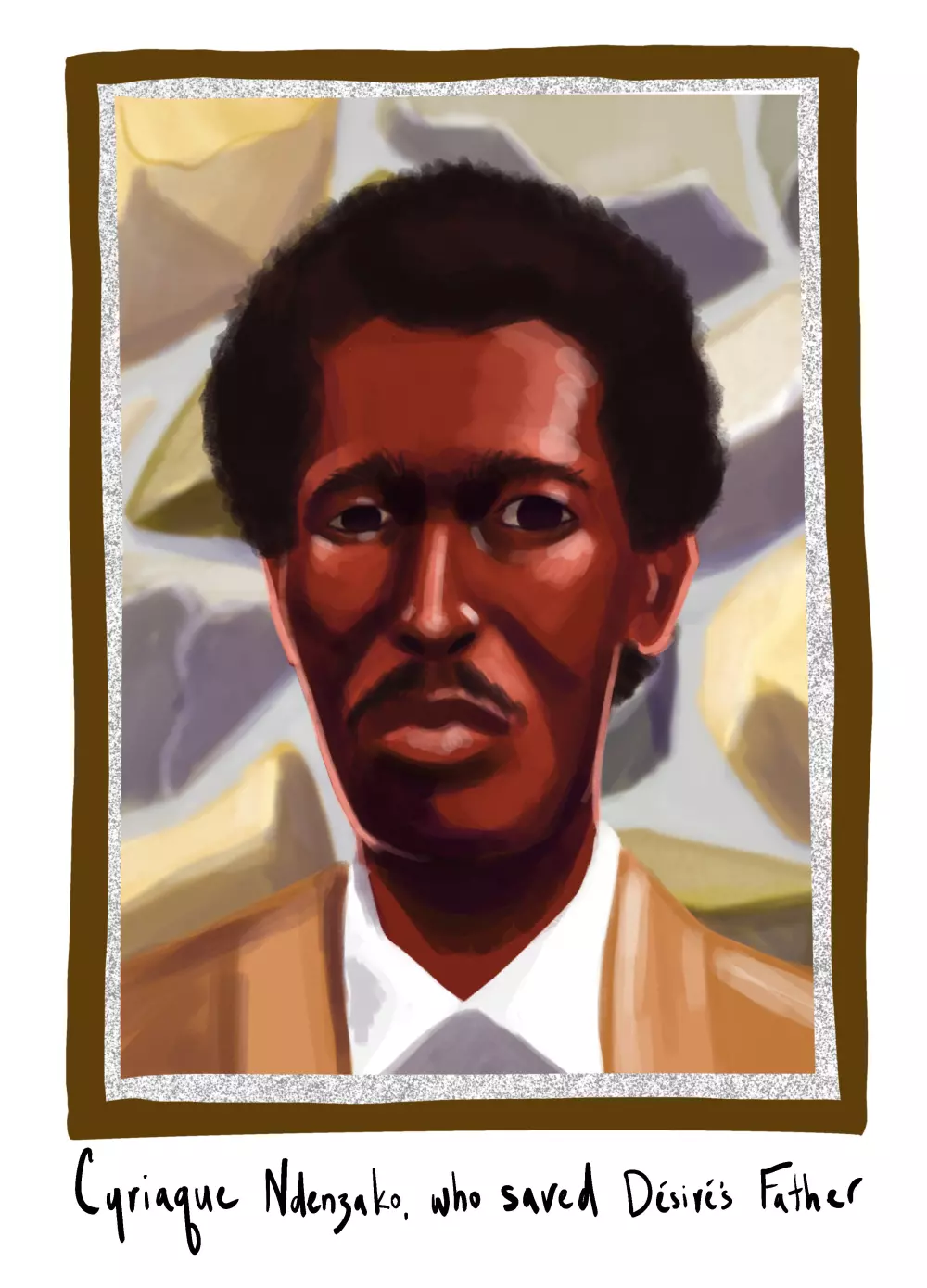

My father, Michael Nditunze, would have lost his life in 1972 if not for the courageous intervention of two Tutsi men – Cyriaque Ndenzako and Pascal Ndikumana – who had been his friends since childhood.

Father had a small business at the time selling clothes, food, blankets, and palm oil in Nyanza Lac, a southern lakeside town. When 1972 came around, he found himself being hunted by gangs of Tutsi youth associated with the military.

Ndenzako, a soldier in the army – who feigned sickness to avoid participating in the killings – risked his life by sheltering father. Ndikumana – a well-respected local businessman – risked his by telling the youths that father had fled.

Our three families have remained close ever since. My sister is a godmother to Ndikumana’s daughter. And I have promised to help support the education of Ndikumana’s son, Havyarimana, and one of Ndenzako's daughters too.

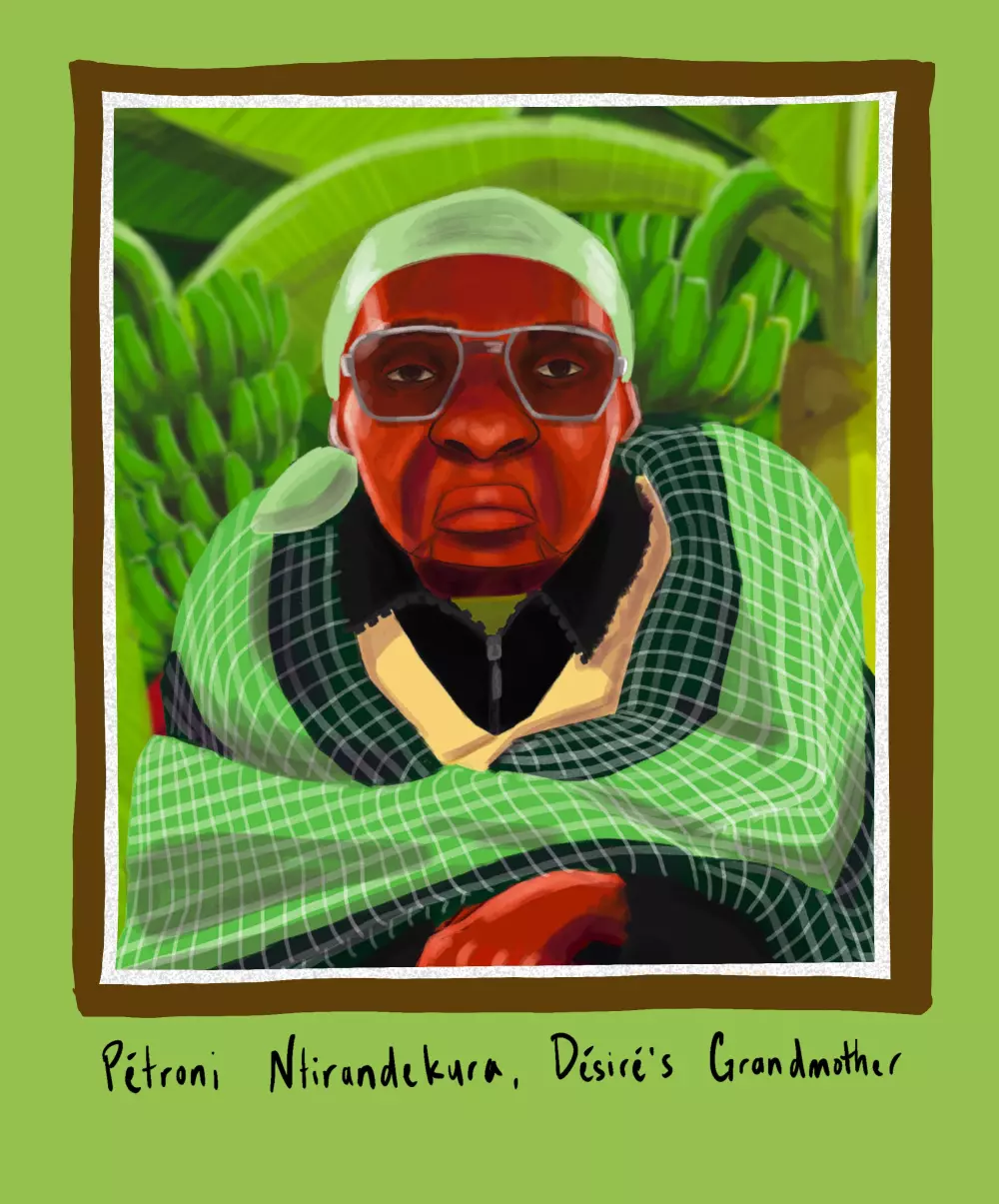

While my father – who is alive and well – owes his life to his friends, other Hutus in Makamba owe theirs to my courageous grandmother, Pétronie Ntirandekura, who died two years ago, aged 85.

In 1972, a group of soldiers drove into her village seeking out local Hutus. To stop the carnage, she walked to the end of a road leading out of the village and removed one of five tree trunks serving as a bridge over a small stream. The soldiers got stuck as they tried to leave, allowing the prisoners to escape via a nearby forest.

A chance encounter and a message to my would-be killer

It is not clear what will happen when the commission finishes its investigations. Though mandated to establish responsibility for crimes, it is not a judicial body with power to prosecute. And though it may suggest reparations be paid to victims, resources here are limited.

By the time its work is completed, however, my hope is that the majority of Burundians will be satisfied with what has been uncovered, and will have some clarity on what happened to their loved ones.

Whether this happens under our current government remains to be seen, but we have to start somewhere. In the meantime, I believe all Burundians must do our bit to forgive each other.

Hear the author speak about how his grandmother saved lives in 1972.

In 2013, I had an opportunity to pursue personal reconciliation. I was working on a story for Radio Isanganiro – an independent station founded to support community reconciliation – about a charity providing legal aid to prisoners.

As I drove towards the entrance of the charity’s office in Bujumbura, a guard walked over to lift the security barrier. It took me a moment to realise who I was looking at: the man who had tried to stab me in my dormitory nearly two decades earlier.

As I left after the meeting, I greeted him and asked if he remembered who I was. At first, he said “no”; then, after a few moments, “yes”. He said he had a lot he wanted to tell me but that he was in a hurry. We shook hands and parted ways.

I heard nothing about the man until a year later when he arrived at my office in downtown Bujumbura unannounced. I wasn’t present, and he didn’t leave his number with the guard on duty.

Twelve months later, a new crisis broke out when our former president stood for a third presidential term. Gunfire and grenade blasts rocked Bujumbura. Some feared a repeat of the past and fled the country.

Last year, I posted on my secondary school WhatsApp group, asking for information about the man. Some people said he had moved to Rwanda; others suggested Uganda. Nobody seemed sure.

Wherever he is – and whatever happens next in Burundi – I hope he knows that my door is always open, and that he is already forgiven.

Désiré Nimubona (pictured here with his grandmother) is a Bujumbura-based reporter, covering Burundi, the Great Lakes, and beyond. He has been writing for The New Humanitarian since 2010, reports for Bloomberg and other local and international media outlets, and is currently an editor at Mongabay working on conservation and environmental science news. He holds a masters degree in international relations, and another in journalism.

(Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Belgium began ruling Burundi after World War II. In fact, Belgium first occupied the country during World War I. This article has been updated on 18 October 2021.)