Far from the air-conditioned meeting rooms of Geneva and New York, it is frontline aid workers who are wrestling with the practical challenges of making the triple nexus – the push to coordinate humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding efforts – a reality. Billions of dollars and millions of lives could be at stake.

But three years after the idea took shape at the World Humanitarian Summit, it is still early days for nexus-focused programming. And with limited independent monitoring so far, it’s hard to get a clear picture of what has really changed – for better or worse.

According to dozens of aid workers, policy officials, donors, and academics interviewed by The New Humanitarian over several months, three things are clear: the nexus is easy to say, harder to deliver, and surprisingly controversial.

As Patricia McIlreavy, vice president of humanitarian policy and practice at InterAction, a US-based NGO alliance, put it: “In recent visits I have taken – Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Afghanistan – there is a heavy focus on the nexus, yet limited understanding of what that means beyond ‘it’s a good idea’.”

Jeff Crisp, a former head of policy at UNHCR, went further: “It’s not really anything new,” he told TNH. “We’ve talked about a lot of this before, and people like to bandy around these terms, but whether they have any real traction, it’s hard to tell.”

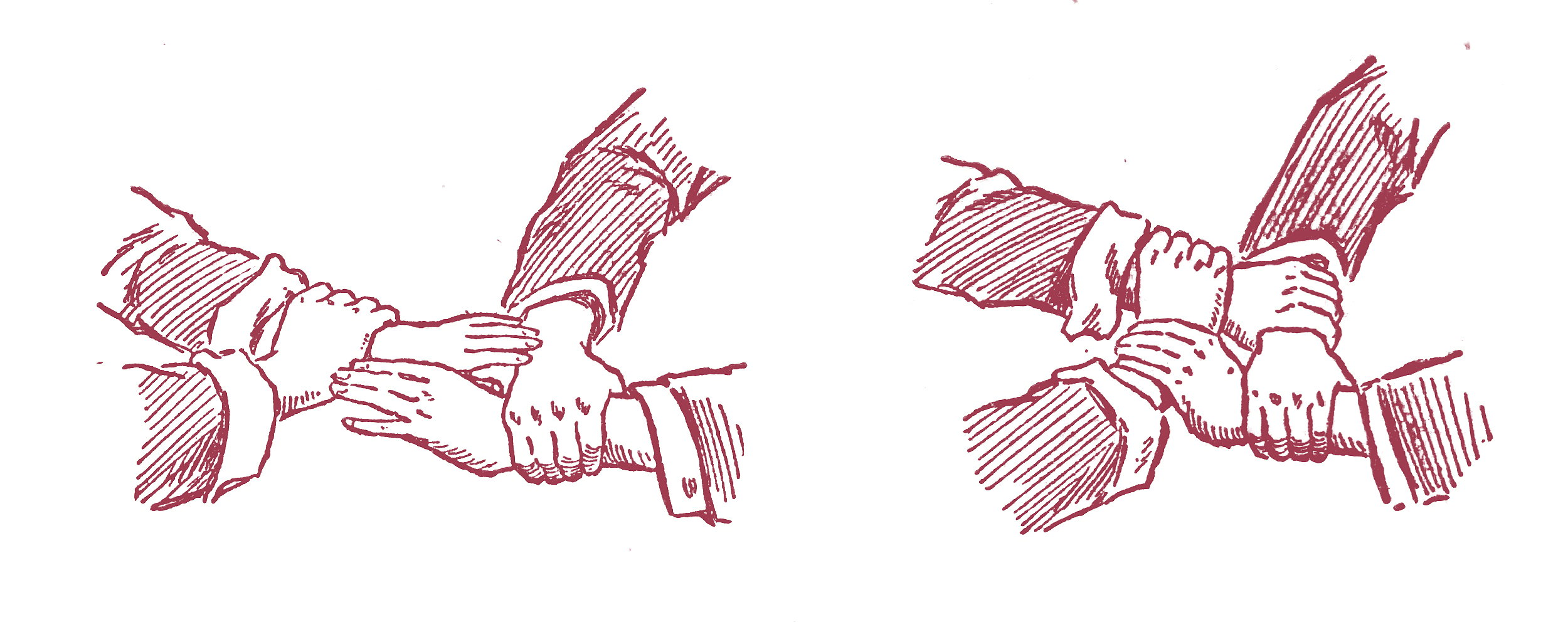

Bigger, longer, and more expensive humanitarian crises have ramped up calls for reforming how aid is delivered – especially as the impact of these emergencies is felt for years if not decades. The triple nexus approach seeks to “break the silos” between peacebuilding efforts and aid’s longstanding frenemies: emergency responders and development workers.

The nexus is more evolution than revolution – other initiatives have come and gone over the last 30 years. Earliest, perhaps, was the Linking Relief, Rehabilitation, and Development (LRRD) concept, which gave way to a new emphasis on resilience-building. Here are a few key events in that evolution.

The Linking Relief, Rehabilitation, and Development (LRRD) concept emerges amid a recognition that a better transition from humanitarian response to longer-term development support is needed, but it is criticised for being too linear and falls out of favour due to the politicisation of development aid in the post 9/11 era. In parallel, the UN starts to use the term “relief to development continuum”.

Calls grow for humanitarian and development actors to work together more closely to help build longer-term resilience and capacity, especially in protracted crises or chronic vulnerability. Conflict prevention, disaster risk reduction, and disaster preparedness come to the fore. “Fragility” takes its place in the lexicon. More than 40 countries sign on to the 2011 New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States, committing to “supporting nationally-owned and led development plans and greater aid effectiveness in fragile situations”.

Global displacement rates soar with wars in Syria, South Sudan, and elsewhere, climate-related tensions, and Islamist insurgencies. With the majority of refugees and IDPs living outside of camps, and many migrants seeking shelter in Europe, governments and agencies must rethink how they respond. The foundation stones for the Comprehensive Refugee Response Frameworks (CRRFs) are laid. The term “compact” is coined for new deals for countries hosting refugees, such as Lebanon and Jordan, to boost their economies and give direct support to the communities where refugees are living.

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set out ambitious milestones to end poverty, hunger, HIV/AIDS, and discrimination against women and girls by 2030. States agree to “leave no one behind” and to “reach the furthest behind first” – this means development planners can’t just work on the easier, middling problems but must tackle the most vulnerable and poorest in society – those that might typically be regarded as a “humanitarian” caseload. The SDGs leverage new thinking in humanitarian circles about how to break the cycle of protracted emergencies and make aid more efficient.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon issues a report ahead of the World Humanitarian Summit, One Humanity: Shared Responsibility. It sets out a so-called Agenda for Humanity: prevent and end conflicts; respect rules of war; leave no one behind; and “transcend the humanitarian-development divide”. Its call to “work differently to end need” shifts the emphasis from better – or more – humanitarian action, to reducing the requirement for it in the first place.

Participants in the World Humanitarian Summit sign up to the Grand Bargain, which lists 10 reform goals – including closer engagement between humanitarian and development actors – aimed at making the aid system more efficient and plugging resource gaps.

The UN begins to roll out its so-called New Way of Working, an approach based on the ideas of the Agenda for Humanity. These include “collective outcomes”; comparative advantages; and multi-year timeframes. Its backers say the approach aims to “strengthen the humanitarian-development nexus” and to “reduce risk and vulnerability and serve as instalments towards achieving the SDGs”.

António Guterres takes over as UN secretary-general and places “prevention” at the heart of his vision for the UN. “We must also bring the humanitarian and development spheres closer together from the very beginning of a crisis… to address structural and economic impacts and help prevent a new spiral of fragility and instability,” he says in his inaugural speech, adding the third dimension of peacebuilding. He describes humanitarian response, sustainable development, and sustaining peace as “three sides of the same triangle”.

The EU – whose member states provide a large bulk of funding for international emergency and longer-term aid responses – announces its intention to “operationalise the humanitarian-development nexus” and creates new funding mechanisms such as its DIZA programme in Chad.

The World Bank’s Pathways For Peace report makes the case for preventing conflict in order to reduce crisis spending, and the bank announces the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Initiative – a pilot collaboration with the UN for integrated responses for those countries at risk of (and already in) protracted crisis and post-crisis situations.

OECD members – rich country donors – agree to “incentivise and implement more collaborative and complementary humanitarian, development and peace actions, particularly in fragile and conflict-affected situations”.

“People don’t live their lives in silos, so we shouldn’t respond that way,” said Fabian Böckler, former programme coordinator for Plan International in the Lake Chad region. “If you want to change anything in this crisis, you need to address the root causes, while at the same time making sure you cover humanitarian needs,” he said, describing the nexus as “obvious and making sense”.

Those in need of aid also want change, according to surveys by Ground Truth Solutions. The research agency’s recent work includes voices from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Haiti, Iraq, Lebanon, and Somalia.

“If we’re serious about the participation revolution, then I think the nexus is a very logical thing for people to demand,” said GTS Deputy Director Elias Sagmeister, referring to survey interviewees. “They will not call it that, but that is the outcome they want.”

Theory meets practice

Long-running “emergencies” such as the multi-layered crises in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Sahel region soak up billions of foreign aid dollars year after year, with no end in sight. Even larger amounts may be spent on development projects with similar priorities.

Meanwhile, traditional models for delivering emergency aid are regarded by many in both the aid and development sectors as too short-termist and even, at times, as contributing to the prolongation of crises.

On the peacebuilding side, studies have found that a lack of sensitivity to specific contexts by aid agencies, such as favouring certain groups or territories, can actually contribute to more tensions and make conflicts worse.

The policy document that came out of the World Humanitarian Summit was a bid to address these issues, as well as to unlock new sources of funding to plug shortfalls amid growing needs – the UN alone is seeking $21.9 billion this year for its emergency aid programmes.

The 2016 document, the so-called Grand Bargain, included a call for joining up humanitarian and development aid, referred to as the nexus. Peacebuilding was later added as the third side of the triangle, creating the triple nexus.

From rich donor nations to the major UN aid agencies, from the World Bank to the Red Cross, the nexus approach is now conventional wisdom at boardroom level. Closer to the ground, however, the idea – and all it entails – is causing eyes to roll and snarky memes to flow.

Frustrated frontline responders told TNH about additional paperwork and meetings. They complained about confused project definitions and scope, leadership issues, and, perhaps most crucially, limited government buy-in hindering genuine cooperation and aid delivery.

For Fie Lauritzen, senior humanitarian policy advisor at the Danish NGO Dan Church Aid, greater alignment between humanitarian and development response is welcome, but there has not been enough engagement with local organisations.

“We are seeing closer working between the donors and the UN on developing priorities and approaches, but we’re not seeing that extended to the local, national, and even international NGOs, or community organisations and civil society groups,” she told TNH. “That’s a big gap. Where are the local actors in the nexus? At the moment, they’re not included, and that is a big omission. We need to do more to engage them if it is going to be a success.”

Lauritzen, who runs nexus training sessions for DCA staff and partners – most recently in South Sudan, Uganda, and Zimbabwe – confirmed there was “a strong commitment to do things smarter”, to integrate better and reduce duplication, but she said there was not always enough “cooperation and coordination” to make it happen.

Some resistance was also evident in the GTS surveys. Although two thirds of the aid workers interviewed in the latest round of surveys completed in 2019 said humanitarian and development actors worked together effectively, that sentiment was held by fewer respondents than two years earlier.

“Even if we manage to come up with this nice strategy, there are still some criteria not in place, like the government engagement, the flexible funding, coordination on the development side etc.,” said one aid worker based in DRC, asking to remain anonymous so they could speak frankly.

“I think sometimes we’re trying so much to conceptualise that we are forgetting this has to work at the operational level.”

The nexus in action

In theory, a more collaborative approach might, for example, fuse emergency food distribution with initiatives to foster agriculture – a modern day teach-a-person-to-fish approach. Another project might aim to reduce land conflicts between villages and help local communities better share resources to address long-term food insecurity and economic challenges.

Instead of carrying out separate analyses and setting distinct humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding targets – such as cutting hunger, increasing crop yields, and reducing community tensions – the UN is starting to establish so-called collective outcomes in a number of settings including Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, DRC, Niger, Somalia, and Ukraine.

Most collective outcomes so far have focused on humanitarian and development alignment, with few very tangible targets set on peacebuilding, which remains the most controversial pillar of the nexus.

In Chad, UN agencies have agreed to work together to reduce the levels of food insecurity by 32 percent; deliver essential water and sanitation (WASH) services to 90 percent of people in need; and cut severe acute malnutrition (SAM) rates in children under five from 2.6 percent to 1.8 percent.

While some of these joint goals are very specific, others are more vague. In Uganda, for example, the collective outcome is: “To support governments to protect and assist refugees and support host communities involved, through a response based on the principle of international cooperation and responsibility-sharing.”

Other aid organisations are also starting to build in nexus elements to their responses – or retroactively tag existing projects as nexus. Some donors, too, are changing how they are funding aid because of the nexus.

The EU is focusing on Chad, Iraq, Myanmar, Nigeria, Sudan, and Uganda, and has set up specific funds to pay for nexus-style programming, while the United Nations Development Programme unveiled in July a $100 million Regional Stabilisation Facility for Lake Chad.

But a lot of these initiatives are still in their infancy, and defining what the triple nexus looks like in practice is not always straightforward.

McIlreavy of InterAction noted “a lot of talk – and meetings – which reiterate the commitment from leadership”, but said she felt “no one at working levels appears quite certain of what it looks like and, more importantly, how to actually implement it.”

One of the first major studies evaluating a more joined-up approach to aid – carried out by the Norwegian Refugee Council and published in June – reviewed how the initiative was playing out in Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, DRC, and Ukraine, with a focus on how financing had changed.

The study noted some real-world benefits – particularly around joint analyses and the recovery and peacebuilding assessments (RPBAs) – which it said helped shape more targeted collective outcomes and greater responsiveness to needs.

But it also pointed out a long list of problems: a lack of clarity on the purpose and scope of greater collaboration; ambiguity around the role of governments; problematic leadership and major gaps in coordination; competition for resources that were disincentivising collaboration; and few new multi-year funding schemes.

“There are far too many incentives to cover up or ignore human suffering in a system change like this.”

Similarly, in its third independent analysis of the Grand Bargain, also published in June, the Humanitarian Policy Group (HPG) at London’s Overseas Development Institute (ODI) also expressed concerns about the lack of coordination around nexus-focused work.

“In the absence of a coordinated strategic approach to integrating the nexus across the Grand Bargain framework,” the authors said, “signatories’ efforts appear disparate and disconnected, missing opportunities to scale up or amplify results, identify and address issues such as the protection of humanitarian principles and ensure appropriate synergies of effort, including investing in local/national responders and increasing prevention and preparedness for early action.”

The NRC study acknowledged it was still early days for the nexus, but noted that interviewees working in the field have little appetite for the “new layers of process and planning” the nexus may demand. It found that competition for donor cash continued to undermine the chances of collaboration, and there were, in any case, still few sources of longer-term funding to tap.

Policy vs. people

The pace of change varies from context to context but, amid increasing competition to be seen to achieve success, some in the humanitarian sector are concerned about bad news getting buried.

Others TNH spoke to pointed out that the neutrality of humanitarian work – which demands that emergency aid is delivered at arm’s length from messy politics – is vital and challenged by a nexus approach that can be more about offering support for long-term change.

“People are building their careers on proving the fact that this is working, and there are far too many incentives to cover up or ignore human suffering in a system change like this,” noted one experienced aid worker with a UN background, speaking anonymously due to institutional sensitivities.

The aid worker questioned how nexus programmes were being monitored and called for closer examination of wider contexts to see who is potentially being denied aid as targets change and responses traditionally led by humanitarians are handed over to national governments or development actors.

Similarly, an academic researching the nexus, said: “Given the competitive funding landscape, agencies are under enormous pressure to tout successes and minimise failures because donors pay attention to that. The way our system is built makes real genuine learning from mistakes very difficult,” said the academic who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of upsetting colleagues.

“At the end of the day, nexus is a mindset, it’s not just one project.”

The researcher described the gap between the official UN rhetoric and the views of people trying to implement the nexus changes within those UN agencies as “problematic”.

“You’re never going to get everyone to agree what success looks like,” the academic added. “But when you talk to people within some of those agencies who have the glowing website reviews, you get a rather different, unvarnished, and oftentimes pretty critical assessment”.

Despite these concerns, support remains elsewhere. Böckler, of Plan International, is convinced the approach can work well in certain contexts.

He said Plan was running a number of nexus-style programmes in the Lake Chad region – projects that simultaneously address humanitarian, development, and social cohesion needs, focusing particularly on secondary education and social protection.

“At the end of the day, nexus is a mindset; it’s not just one project,” he said. “If you believe in it, then your whole programming approach will change.”

But it appears that change will take a lot more than the three-plus years that have already elapsed since the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit.

Leah Zamore, who directs the humanitarian crises programme at New York University’s Center on International Cooperation, said the jury is still out on whether the nexus approach will deliver on its goals – to better assist millions of people and more effectively spend billions of aid dollars.

"The aspiration is systemic change,” she noted. “And that invariably takes time."

lr/bp/js/ag/pd