Despite the Egyptian government’s deployment of additional troops to its restless northern Sinai region, attacks by Islamist militants continue, and almost inevitably civilians are being caught in the violence.

Last month, a suicide bomber rammed his car into a bus carrying off-duty soldiers, killing 10, including the civilian driver. Although no one claimed responsibility, the attack bore the hallmark of the al-Qaeda inspired militants the Egyptian army has been trying to suppress.

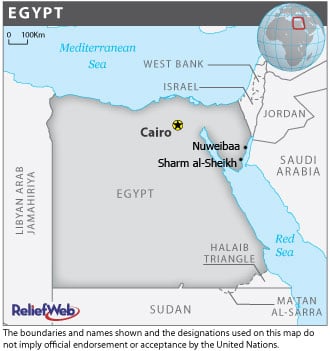

The marginalized Sinai Peninsula has been unstable for years. Growing Islamist militancy announced itself with a string of sabotage strikes on gas pipelines to Israel in 2011, and attacks on security forces. After attackers killed 16 Egyptian soldiers at the border with Israel in August 2012, Israel allowed Egypt to send additional troops to the area, a measure usually forbidden by a peace agreement between both countries. A period of relative calm under former president Mohamed Morsi ended with his ousting in July, leading to a spike in violence. The government stepped up its military response after the attempted assassination of Interior Minister Mohamed Ibrahim in September.

But the army has struggled to locate its enemy in Sinai - a combination of Egyptian or foreign jihadists and local Bedouin tribesmen with grievances. Army sweeps through some villages have been accused of killing and injuring civilians uninvolved in the insurgency.

When 65-year-old Safa’a* saw an army patrol coming towards her home in the village of al-Moqata’a, south of al-Sheikh Zuwaid town, on 8 September, she refused to leave.

“We stayed in the house because she didn’t want to leave it, and they [usually] only arrest men,” said her daughter-in-law, Aya*. “We thought they wouldn’t shoot at the house, [but]… the soldiers didn’t check the house was empty before they starting firing.”

According to relatives of the deceased, Safa’a was one of two people killed in al-Moqata’a during two days of military operations there in early September. The village would be targeted again and again in the following weeks.

“We didn’t get a death certificate accusing the army because it would cause us trouble,” Aya said.

Security sources told the media that these same operations led to the deaths of armed jihadists and the arrest of the “leader of al-Qaeda in Sinai”. An armed group in Sinai, al-Salafiya al-Jihadiya (Salafist Jihadism), accused the army of achieving nothing but the arbitrary killings of civilians.

Egyptian authorities say they lost more than 100 police, soldiers and conscripts between July, when the insurgency in Sinai escalated, and October. Samir Ghattass, director of the Middle East Forum for Strategic Studies, puts that number at 124.

In its months-long campaign in North Sinai, the army boasts of many deaths among “terrorists” (165 as of 14 November).

“We have killed or arrested many of them,” General Samih Beshadi, the government’s head of security in North Sinai, told IRIN. “Most of the rest of them have now fled or are hiding. Of course, because of the geographical nature of the desert area, the task is difficult, but we are very successful.”

According to David Barnett, of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a Washington-based think tank, monthly attacks by militants dropped from 104 in July to 23 in October, though they rose slightly in November.

The army admits few, if any, civilian casualties.

“We take great care of civilian lives,” Egyptian military spokesperson Colonel Ahmed Ali told IRIN.

But some residents say they have paid a heavy price: civilian deaths; destruction of homes, property and livelihoods; displacement; and little hope for compensation.

Armed militant groups have also disrupted civilian life. (See IRIN’s article on that here)

Civilian deaths

In addition to the two deaths in al-Moqata’a, a jihadist group reported seven civilians, including four children, were killed in al-Fitat Village, south of al-Sheikh Zuwaid, on 13 September, during military operations in the village. While residents of the area supported the claims, IRIN could not independently verify them.

A local journalist, who requested anonymity for fear of repercussions by the army, told IRIN several people who were mistaken for militants by the army or police had been killed. They include two men killed in a taxi in al-Arish town; two people, including a child, killed at a checkpoint in al-Sheikh Zuwaid; and two people killed in al-Gora Square, also in al-Sheikh Zuwaid, during clashes between militants and security forces.

One of the dead was Mostafa Nasser, 63.

According to his son, Ali, Nasser had mixed up the time and left a pharmacy, located next to the police station in al-Sheikh Zuwaid, one hour past curfew.

“The police pretend there was an attack on the police station, and eyewitnesses affirm there wasn’t. In any case, my father… had nothing to do with it,” Ali told IRIN.

Nasser was shot and killed.

“The governorate of al-Arish phoned me up to let me know there would be a compensation since his death was a mistake, but that I had to hold on,” Ali said.

Displacement

The government’s counter-insurgency operations have also resulted in some displacement, say families.

Sami*, a resident of Rafah, said he was forced to move in with relatives in al-Mehdiya Village, south of Rafah, at the beginning of September, after his home was destroyed by the army.

He said nine families had fled al-Mehdiya; some left for the towns of al-Sheikh Zuwaid and al-Arish, others for the capital, Cairo. “Most of the people are not living in the village anymore,” he said in October.

“My olive and peach trees are chopped down,” Sami said. “I can’t decide to go back and rebuild until I know what the army’s up to, if they will not come and destroy everything again.”

In any case, he said, he is unable to rebuild his home. Trade has stopped and an early curfew has limited the transport of construction materials.

A few days after IRIN spoke to him, Sami’s relative’s home was also destroyed.

Samia*, another villager, said her sister had resorted to living in a yard after her home was damaged, and that her cousin had fled to Cairo.

According to Mohamed Abdullah, head of relief at the Egyptian Red Crescent, the number of civilians killed or injured in operations was “limited”. He told IRIN in November he was not aware of any major displacement in the area.

The Red Crescent stood ready to provide tents, blankets or other aid, he said, but its branches in Sinai had not received requests for assistance. The governorate and the army, he added, were well-equipped to respond in cases of humanitarian need.

“We provide assistance in big crises, like flash floods, earthquakes and if a war is going on,” said Abdullah’s deputy, Mohamed Ahmed, “but as I see it, there is no war going on.”

Others acknowledge the human cost, but say the ends justify the means.

“Yes indeed, it involves operations which affect the civilian population there,” said Ehud Yaari, a fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “It’s not nice, but that’s the only way to deal with the threat that emanates from the Sinai Peninsula towards mainland Egypt and the Suez Canal.”

Destruction of homes

While some villages of northeastern Sinai have not been touched by the counter-terrorism operations, others have been targeted several times, leading almost the entire male population to flee - at least while operations are ongoing.

For example, when IRIN visited the village of al-Moqata’a, which has been raided three times, during the Eid holiday in October - a time when families usually gather to celebrate the feast - it was half empty, more than a month after major military operations in the village.

Many homes were flattened to the ground. Others had large sections blown away, gaping holes in walls pockmarked by bullets, and signs of burning. And some houses, sitting beside the damaged ones, were untouched.

One resident of the border town of Rafah said around 25 civilian houses had been destroyed in mid-October.

IRIN also saw that many olive tree orchards, located next to destroyed houses, had been shaved to the ground. Olives are the main agricultural source of income for this part of Sinai, but militants have hidden in the trees lining the road to ambush army convoys.

According to the authorities, “terrorists” are the only target of operations.

“As for the houses we target,” said army spokesperson Ali, “they are all criminals’ houses or operations sites or weapons storage places. When I say ‘criminals’, I mean anyone who is against the law, terrorists, and drugs, weapons and human traffickers.”

Security chief Beshadi said the army and police forces “are dealing with the terrorists so they will not come back.”

But local residents in al-Mehdiya say the security forces attacked houses at random, including the homes of people who had no links to armed groups. IRIN spoke to five families who said their homes had been wrongfully targeted. They said they were not informed before the destruction of their homes and have received no word on compensation.

Marwa* and her nine-year-old daughter barely had time to flee when the army attacked their home, located some 100m from that of a known militant. The girl was injured in the process: a piece of shrapnel entered her cheek.

“I didn’t hear anything from the army except when they blew the house up with TNT,” Marwa’s husband said. “The arrest warrant was against my neighbour. He fled before the attack. A week after, they attacked my house, they came back to flatten his.”

Collective punishment?

In many cases, the army does get its targeting right.

Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis is a jihadist group that has taken credit for attacks on the North Sinai pipeline, on security forces in Sinai, on army “collaborators” and on the interior minister in Cairo. In al-Mehdiya, the home of Shadi el-Menai, said to be one of the founders of the group, has been flattened to the ground.

But so, too, have the homes of all his family members.

“Men here have fled; they don’t even tell their wives where they’ve gone. Nobody takes care of the fields anymore,” said a female relative of el-Menai. “The army says everyone is a terrorist. If you have a long beard, you might get killed just for that.”

But army spokesperson Ali insists the people of the area support the army’s operations. “We have the same aim. We want to restore security to make it a suitable environment for development.”

Indeed, some residents, like Khaled el-Menai, argue all of those targeted have “bad ideologies” or “keep silent” about the militants in their midst.

Khaled belongs to a wealthy, important family of the el-Menai tribe, one of the most powerful in North Sinai (the same tribe Shadi el-Menai belongs to). Militants killed his father, Sheikh Khalaf el-Menai, and one of his brothers last year, allegedly for cooperating with the authorities. Another brother, Suleiman Khalaf el-Menai, was reportedly killed by militants in October.

“The army doesn’t attack randomly,” Khaled el-Menai told IRIN. “Yes, there were mistakes, and we are all sorry for it, but they’re looking for criminals, weapons, drugs - all of which finance the spread of the bad ideology.”

Before the military operations in al-Mehdiya and al-Moqata’a, the military asked local sheikhs to turn over the militants in the area, Khaled said. Instead, “they went back home and turned off their phones… The army felt that the majority of the people in the villages are silent about those - the minority of terrorists - living among them. That makes them criminals as well.”

His brother Walid added: “In al-Mehdiya Village, there were maybe four or five extremists; the rest of the village didn’t mind. If the society had done something against them at the beginning, we wouldn’t stand where we do now, but the time has passed. Those who stayed silent for years should be [punished].”

Buffer zone?

In December 2012, the government banned - in Law 203 - the private ownership, rental and use of nearly all land within 5km west of the border, with the exception of the border town of Rafah. At the time, the army said the decree was designed to help the government cope with threats to Egypt’s national security on its eastern borders.

Beshadi says the armed forces’ current aim is to create 1km-wide empty zone, where “it will be easy to fight terrorists”.

“Egyptian security is a priority,” Ali said. “You cannot have your house on the border line and prevent us from seeing threats clearly.” He said residents living within 1km of the border would be compensated for the destruction of their homes.

But residents said some of the targeted homes fell outside the 5km zone, let alone the 1km zone. The army also appears to be targeting upscale homes outside the 1km zone on the assumption that the wealth of their owners was illegally acquired via smuggling and the trafficking of weapons and other goods to and from Gaza. (See IRIN’s piece on the impact of the anti-smuggling operations on the economy of North Sinai)

Compensation

Some affected people have contacted local human rights groups, but few are optimistic about accountability on the authorities’ side.

“We cannot ask for compensation,” said a Rafah resident whose house was destroyed “for no reason at all”. (The authorities accused him of harbouring a smuggling tunnel under his home.)

“If we file a complaint,” he continued, “who will judge? And who can help? Human rights organizations can be switched on and off by the government.”

At the beginning of October, defence minister and de facto leader of Egypt Abdel Fattah al-Sisi thanked Sinai's residents “for their patriotic role” and apologized: "We undertake procedures that may be inconveniencing them, and we promise to compensate them for [damaged] land or buildings that collapsed."

*not a real name

sa/ha/rz/oa

Also in the series Sinai: Destined to suffer?

- Egyptian civilians in crosshairs of Sinai militants

- Economic life slows to a crawl amid crackdown in North Sinai

- Egypt's revolution brings little to underdeveloped Sinai

This article was produced by IRIN News while it was part of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Please send queries on copyright or liability to the UN. For more information: https://shop.un.org/rights-permissions