In a move that has prompted dismay from Yemeni authorities on both sides of a five-year war, the World Health Organisation is reducing top-up payments to thousands of healthcare workers across Yemen, even as COVID-19 is starting to spread through the country.

Despite the UN predicting a “terrifying” impact from the coronavirus in Yemen, the WHO says it doesn’t have the money to carry on with the payments. “Very simply put, I just don’t have the funding to sustain lifeline programmes [like this],” said Altaf Musani, the UN agency’s representative in Yemen, describing funding cuts to the humanitarian response in the country at this time as “dangerous”.

The WHO has been paying “incentives” to doctors, nurses, and other health professionals across Yemen for the past few years, intended as a stop-gap measure to help the country’s decimated health system continue to function as both the internationally recognised government of President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi and the Houthi rebels – officially known as Ansar Allah – failed to regularly pay civil servants.

The Houthis and Hadi’s government, backed by a fractured Saudi Arabia-led coalition, have been fighting for control of the country since 2015 in a conflict that has killed an estimated 112,000 people in direct violence, with many more dead of disease and hunger.

The incentive payments are not the only health programmes on the chopping block. Unless it secures more funding, the WHO says it faces a $150 million shortfall in Yemen and will have to cut support for supplies for health centres, trauma care, and the treatment of chronic conditions like cancer – even as COVID-19 cases are being recorded in both the Houthi-run north and the Hadi-allied south.

As for the COVID-19 response in Yemen, that will take more funding. Even if sufficient mitigation measures are put in place, WHO models predict the virus could kill at least 42,000 people (very possibly more) and see the vast majority of the population infected.

Subscribe to our coronavirus newsletter to stay up to date with our coverage.

Musani confirmed the incentive payments would be phased out, although he said some healthcare staff working on emergency COVID-19 response and cholera would be paid up to June, and workers at therapeutic feeding centres for malnutrition up to August.

“My deep worry is that in light of COVID-19 we have created the perfect storm where healthcare workers are doing their jobs, now they don’t have incentive support, and we don’t know about the sustainability of their salaries [from authorities],” he told The New Humanitarian. “They continue to serve, but we are putting additional pressures and risks on them.”

NGOs that work in the health sector were wary of speaking on the record, but one official, who asked to remain anonymous, said that since salaries and incentives had already been spotty, and devalued by massive inflation, they were concerned health workers would feel unable to continue doing their jobs.

“People continue to work and serve their communities,” the NGO official said. “But this is a serious concern… we don’t want to get to a point where there is a zero staff level at health facilities.”

‘Serious consequences’

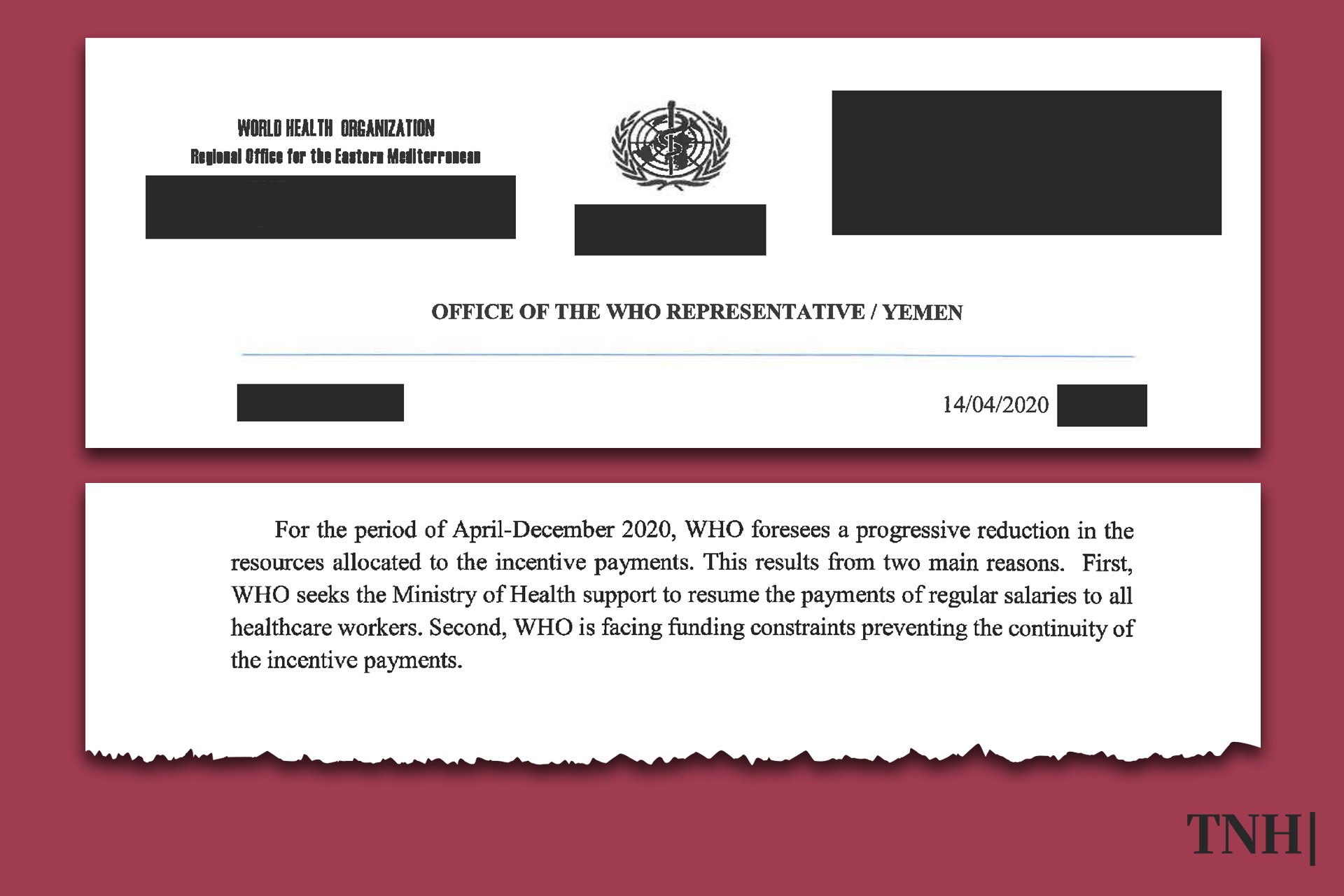

While discussions had been ongoing about phasing out the programme for months, the Houthi authorities and Hadi’s government were only officially informed of the shift by letter in mid-April.

The 14 April letter to the Houthi ministry, signed by Musani and seen by TNH, “foresees a progressive reduction in the resources allocated to the incentives payments”, and gives two main reasons for the change: the WHO has funding constraints, and it also wants the Ministry of Health to resume making regular salary payments itself.

According to the letter, the WHO transferred 16.8 billion Yemeni rials (around $68 million) in 2019 to over 9,600 health workers “allowing for their retention and continuity of service”. A different WHO document, also seen by TNH, puts the number of health workers receiving incentives last year at over 7,900, out of a targeted 30,000.

While it’s unclear exactly how many health workers are or should be on the state payroll, the workforce was estimated at 33,000 in a 2016 survey. An August 2019 aid report said many health workers had either stopped working or returned home because of the war, and those still working “largely depend on incentives offered by the humanitarian actors to sustain the facilities remaining functional”. It added that “the dependence of the Yemen health system on incentive payments… poses a huge risk”.

According to the minutes of a 29 April meeting (also seen by TNH) of Yemen’s health cluster – a WHO-led group of other aid agencies and NGOs – the reaction of both rival health ministries was “not pleasant”.

Ali al-Walidi, deputy health minister in Hadi’s government, told TNH he had been informed that – due to WHO funding shortages – the incentive payments would be decreased and certain health programmes would be closed down.

According to the minutes of a 29 April meeting of Yemen’s health cluster – a WHO-led group of other aid agencies and NGOs – the reaction of both rival health ministries was “not pleasant”.

The end of the incentives “would have serious consequences in light of the extraordinary circumstances [in Yemen]”, he warned. “We have demanded... the continuation of all programmes implemented by the WHO.” Al-Walidi said some workers had already complained of delayed incentives.”If they’re cut entirely,” he said, “it would definitely have dire consequences on the overall health system in these difficult circumstances.”

Al-Walidi insisted health workers were being paid by the Hadi government, but said the salaries were so low that doctors and nurses may not risk turning up, especially given COVID-19. “They’re unlikely to go and work in an isolation ward or a laboratory [without the extra incentive payments],” he said.

A spokesperson for the Houthi health ministry in Sana’a referred TNH to Adnan al-Haj, general director of the technical division. Other officials could not be reached for comment.

Al-Haj said he wasn’t aware of the planned cuts, but warned of serious problems if they went ahead. “The current situation we are in is extraordinary, with Yemen regarded as the country with the most humanitarian need, and the health sector is the most important,“ he said. “It serves everyone, and its collapse has dire consequences.”

“Any decrease of support provided by the donors... anything that hinders constant aid support, especially now with the first confirmed cases of coronavirus… what justification can there be for this?” he asked.

Al-Haj added that he wasn’t sure exactly how many salaries his ministry was paying, but noted that the economic situation didn’t allow them to be paid regularly. “First, the aggression must come to an end, letting Yemen utilise its natural resources,” he said. “Then ask about paying salaries.”

Donor pushback

The WHO’s Musani told TNH he was well aware of the negative reactions from both sets of Yemeni authorities. “To say they are upset with us is to put it mildly,” he said. “They say that the timing couldn’t be worse, and we say ‘we agree, talk to our donors and partners.’”

Meeting Yemen’s humanitarian needs would be the world’s most costly humanitarian operation in the world today if it were funded to the level the UN says is needed – it has asked for $3.2 billion in 2020, and received less than one third of the target.

Some 80 percent of the population, 24 million people, need help and the UN aims to help 15 million of them. However, donations this year have not matched the needs assessed by the UN and other aid groups. Pervasive corruption has dented donor confidence – the United States has cut back in exasperation – and aid operations rely heavily on Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which provided over half of last year’s funding.

International aid groups support some 2,500 health facilities, 60 percent of those that still function, and Musani pointed out that health funding was low across the board. “This is not necessarily a WHO issue. This is a defunding issue based on risk management,” he said. “Health partner NGOs have also been defunded, and have had to cut back services.”

The WHO is not alone in paying “incentives”.

International organisations often pay extra allowances to health workers in government clinics and hospitals taking on more work during crises. This is done to motivate staff despite low or non-existent wages from the state. When top-ups are meant to increase regular paychecks, the funds are usually via the employer, such as a health ministry, which provides lists of eligible staff, but they can also be paid to the individual.

A donor official, who spoke to TNH on condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of the issue, said they were not opposed to incentives in general, but over time the system had become chaotic and unregulated.

For example, various aid groups may pay the same workers different incentives on parallel projects. In addition, the official said, they are sometimes paid to institutions – including hospitals connected with the Houthi authorities – that donors don’t recognise as legitimate, so they can’t be sure the money will trickle down to the right people.

Musani said the WHO had made great strides in standardising payments, including making sure people were paid equal amounts for equal work.

However, according to an internal 2018 audit summarised in a May 2019 report, the WHO could not fully track its spending on incentives. “Monitoring of third parties was partial or inadequate for direct implementation activities such as payment of incentives and delivery of fuel and water to health facilities,” it says.

Some Yemeni health staff may still benefit from incentives from other aid projects, and the WHO pays health workers in other ways, including per diems and hazard pay.

In response to questions from TNH, UNICEF said some of its support to healthcare facilities is intended to go to staff, including contributions for travel and some of the payments they give to hospitals that provide emergency obstetrics and newborn care.

“An interruption of incentives will definitely affect the ability of the health workers to continue working, with far-reaching consequences on the population, especially the most vulnerable such as children and women,” the agency said. “UNICEF continues to engage and urge donors to continue providing the funding required for the incentives so that lifesaving health services can be provided.”

The UN agency stressed that both sets of authorities in Yemen had begun to pay salaries again, if irregularly, and that incentives were meant to be add-ons for people working in dangerous environments or on specific programmes, rather than replacements for government wages.

Musani also stressed that the WHO was not meant to be a replacement for the state. “We are a provider of last resort,” he said. “We fill gaps, when needed, but we are not a government or a donor.”

With additional reporting from Shuaib Almosawa.

aj-bp/ag