When Romelie Kawgho’s boyfriend returned from his Ebola checkup in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo in January, he told her he was cured. The 25-year-old Ebola survivor had been discharged from a treatment centre three months earlier and insisted on having unprotected sex with her.

Although doctors urged the couple to use a condom for a year, Kawgho’s boyfriend assured her he was fine. Months later, after repeatedly having unprotected sex, 19-year-old Kawgho found herself in an Ebola isolation ward fighting for her life.

Now an Ebola survivor herself, she wishes she had been better informed.

At a glance: Key findings

- Risks associated with sexual transmission or breastfeeding are not part of the general prevention messaging in the Ebola response.

- A large number of people TNH interviewed were unaware of the transmission risks associated with unprotected sex or breastfeeding; few knew survivors could be contagious even after they had been cured.

- Community outreach workers admitted being confused by guidance on sex or breastfeeding risks, sometimes omitting information.

- Better treatment and vaccines have led to a growing community of survivors in the latest outbreak, but medical evidence shows survivors can still infect people.

- Ebola can live in the semen of survivors for more than a year, while the virus has also been found in the breast milk of mothers.

- Women and children are hardest hit in the outbreak that has killed 2,200 people and counting. Roughly 70 percent of cases have been women and children.

“I didn’t know many things about Ebola,” she said. “Had it been explained before about sexual transmission – if I knew everything – it would have been good, and I would have forced him to use a condom.”

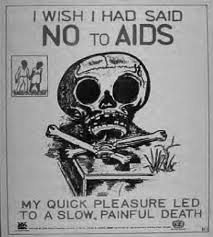

When HIV swept across much of Africa in the 1980s and ‘90s, people were warned that unprotected sex, breast milk, and exposure to other bodily fluids could put them or their children at risk. In the latest Ebola outbreak, however, warnings about sexual transmission and breastfeeding have been inconsistent, while a stark reality has emerged: most Ebola victims are women and children.

As the primary caregivers to children and relatives, women have been hardest hit in an outbreak that has killed 2,200 people and counting. Roughly 70 percent of the more than 3,300 cases have been women and children, according to UNICEF, one of the lead UN agencies helping with prevention messaging.

New vaccines and treatments have contributed to more people recovering from the disease, but recent studies have also shown that the virus can live in the semen of male survivors for more than three years. The virus has also been found in the breast milk of survivors who showed no Ebola symptoms. As of 28 November, there have been 1,077 survivors from the latest outbreak.

While risks associated with sexual transmission and breastfeeding are touched upon during follow-ups with survivors, there is no set "protocol" to include such warnings in general prevention messaging, according to David Gressly, the UN’s emergency Ebola response coordinator. “The communications working group is currently developing messages and communication tools adapted to communities on the topic,” he added.

Jason Kindrachuk, an assistant professor at the Department of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases at Canada’s University of Manitoba, is working with his own team and local researchers in Sierra Leone to identify if survivors from the 2014-2016 West Africa outbreak – the deadliest ever, which claimed more than 11,000 lives – have experienced long-term reproductive health issues.

“My concern is that we always thought such cases, such as transmission through sex, were just outliers, and now we’re actually realising it’s a big public health concern – in particular for outbreak containment,” said Kindrachuk. “Organisations have to do a better job of reaching out to communities.”

Controlling the spread

Containing the latest outbreak in the remote eastern provinces of North Kivu and Ituri has been particularly difficult. Violent attacks fuelled by rumours the virus isn’t real or is being used by the government to eradicate opponents or make money have repeatedly led to the suspension of response activities and stalled progress.

Six health workers have been killed, and dozens more have been injured in more than 300 attacks since January, according to the World Health Organisation.

The number of cases had slowed in October, but recent protests and clashes between the Congolese military and armed groups forced the suspension of response efforts, with the WHO voicing concern that the latest violence and stalled response efforts could reverse hard-won gains.

Ebola is not an airborne virus, but it is highly contagious. People can contract the disease by coming into contact with bodily fluids such as vomit, faeces, blood, or semen that enter the body through cuts or membranes. Ebola can also survive on surfaces for several days, and there has been some evidence that it might be found in saliva and tears, according to the WHO.

Such risks have been articulated on various UN websites and those of government agencies like the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But on a trip to the Ebola-affected areas in October, a large number of the 30 people TNH spoke with in different towns said they were unaware of the risks of sexual transmission or breastfeeding and did not know that Ebola survivors could still transmit the virus.

“I thought that once you’re cured, you’re cured,” said 43-year-old Paul Kasereka.

Some locals and experts also worry that in a culture where men often refuse to wear condoms, the increasing number of survivors could fuel more outbreaks. Charlene Mgononbi, a nurse working with the health ministry at an Ebola centre in Butembo town said she doesn’t trust men to wear condoms.

Maurice Kakule Mutsunga, head of an association formed by Ebola survivors since the onset of the current outbreak, described getting men to have protected sex as “very hard to control”.

Mutsunga was the first known survivor of the latest outbreak. He believes he infected his wife through unprotected sex before he knew he had Ebola. She has since recovered.

"We know that Ebola affects women and children more than others.”

Rachel Kavughokahuko, meanwhile, lost her husband, her two-and-a-half-year-old daughter, and her mother-in-law to Ebola. Cradling her two-month-old son while she breastfeeds, the 29-year-old survivor said her breast milk tested positive for Ebola four months after she was cured. She has since been told she can breastfeed safely, after having two negative results since September.

"We know that Ebola affects women and children more than others,” said Pauline Schibli, Ebola programme director for Mercy Corps, an NGO involved in the response that is pushing for clearer messaging on transmission risks.

“We need more research into how the disease is spread through breastfeeding and sexual transmission, and consequently more guidance to include in our programmes so we can prevent the most vulnerable from being infected."

Lack of research

Posters on roadsides warn people not to touch sick friends or family members, to wash their hands, wear protective clothing if touching contaminated clothing and objects, practise safe burials, get vaccinated, and avoid sick or dead bush animals – known to be carriers of the virus. But the posters about prevention measures seen by TNH didn’t mention sexual transmission or breastfeeding.

While it’s known that Ebola can survive in sperm and breast milk, it is difficult to pinpoint precisely how the virus has been transmitted, and studies tracking survivors are still in their infancy.

“It takes so much time and resources to identify route of transmission for each case for Ebola epidemiology,” said Eta Ngole, a doctor working on the Ebola response. “The priority now is on identifying suspected cases early, isolating them, confirming them using lab tests, following up on contacts, and providing care.”

While proving that a person contracted Ebola through sex or breastfeeding is difficult, it is possible to have a high degree of certainty, especially regarding sexual transmission.

Male survivors containing the virus in their semen do not carry it in their blood, so if a male survivor’s semen tests positive for the virus and he has sex with someone, the likelihood that sex was the mode of transmission is high, explained Kindrachuk, from the University of Manitoba.

Sequencing the virus with machines can allow medical personnel to look for similarities in viruses in two different people, and is a technique increasingly being used to trace transmission events in outbreaks.

Even though it can’t detect unique signatures that will link viruses back to a specific person, it can help infer who the virus came from based on how closely aligned one person’s virus sequence is compared to another, explained Dr. Susan Poutanen, a medical microbiologist and infectious disease specialist at the University of Toronto.

Since the West Africa outbreak, there have been significant medical advances, specifically with regards to the speed and mobility of sequencing. Researchers are now able to sequence virus samples within hours, whereas before it would take longer. And, due to new portable equipment, sequencing can also now be done in almost any location, instead of having to do it in a laboratory.

The technology can now be more easily used by people in developing countries, meaning there’s less reliance on international organisations. It has also provided greater opportunity for surveillance of animals in the bush, which makes it easier to track the virus to wild animals known to host it.

But it’s a lot harder to pinpoint the mode of transmission for Ebola survivors who are breastfeeding. If a woman’s breast milk tests positive for the virus, her blood can still be positive, making it less clear how she might have passed the disease onto her child.

There is also insufficient research into precisely how long the virus can survive.

Different studies have found that the virus can survive in breast milk anywhere between 26 days and 16 months.

But Cavan Reilly, a professor of Biostatistics at the University of Minnesota and one of the authors of an Ebola study from the New England Journal of Medicine in March, said his team was unable to detect the virus in survivors’ breast milk about a year after they were infected.

Reilly’s group investigated survivors starting a year after infection and sampled them for approximately two years. A total of 94 survivors were tested 397 times, and no positive breast milk samples were detected. He said the findings indicate that more studies need to be done about whether the virus can be found in breast milk during the first year after infection.

The messaging on the risks associated with breast milk is particularly difficult in a region where people have limited resources, according to Rigo Fraterne, country director for International Medical Corps.

If women are told not to breastfeed, there need to be alternative feeding options, which can become an economic burden for families, said Fraterne. Even though survivors are given supplemental milk by UNICEF, some villages don’t have access to safe drinking water, so even when milk is available there is the added challenge of preparation, he explained.

“The repercussions from this lack of clarity on transmission of Ebola via breast milk are potentially enormous,” said Mija Ververs, author of an Ebola publication in the Lancet and senior associate at the Center for Humanitarian Health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

During the HIV response in the 1980s and ‘90s, the main prevention messages were to avoid breastfeeding and practise safe sex, said Dr. Sumon Chakrabarti, head of the infectious disease unit at Trillium Health Partners Hospital in Toronto, and a specialist in tropical medicine. HIV testing is faster and easier to trace than Ebola because there are multiple tests that can be done that aren’t as labour-intensive in terms of processing samples, added Chakrabarti.

There have been 33 cases up until March 2016 of possible, probable, or confirmed Ebola transmission through sex, according to a 2018 report in Viruses, an online medical journal.

Mixed messages

The lack of research or conclusive studies into the prevalence of transmission through sex or breast milk may be contributing to mixed messages about the risks.

For example, when Kawgho’s boyfriend said he was cured, the couple was told to use a condom for one year. But Kawgho said other survivors she knows were told to use a condom for two-, three-, or six-month periods. Kawgho, who doesn’t have children, also said she wasn’t told anything about breastfeeding.

The Ministry of Health says the risks of having unprotected sex and/or breastfeeding have been communicated in prevention messages broadcast on the radio. Only two of the dozens of people TNH interviewed had heard prevention messages on the radio. One of the radio stations meant to be broadcasting such messages shut down recently after one of its journalists was killed in an attack.

The government also doesn’t give timelines on how long the virus can remain present in survivors because every situation is different, said Justus Nsiso, deputy coordinator for the Ebola response with Congo’s Ministry of Health.

“You can’t tell someone not to have sex or breastfeed for nine months if after one month they turn out to be negative,” he said.

Messages across leading agencies are also conflicting.

UNICEF has been the lead for all community engagement and risk communications since the end of July, according to Margaret Ann Harris, WHO spokesperson in Congo. Before July, WHO was the lead on messaging, but worked in partnership with UNICEF, she said.

According to UNICEF, breastfeeding information is only given to Ebola survivors and not to the general public.

“It might panic people,” said Mariama Sire Kaba, a community engagement specialist with UNICEF. “The population is already very sensitive about Ebola. If information is forced upon them, it won’t work.”

But aid groups like Mercy Corps think people have the right to be provided with all the facts.

When the HIV epidemic tore through Uganda, for example, infection rates were thought to have been reduced through the government’s aggressive messaging campaign.

“We know that when people have accurate information – for example about the spread of cholera – we see a significant decrease in transmission,” said Schibli, of Mercy Corps.

Volunteer health workers who go door to door to speak to communities about Ebola prevention told TNH they are often unsure what to tell people.

Valance Kahindo sometimes omits information about transmission through sex and breastfeeding because she said the data is confusing. “I have my numbers, but I’m realising everyone has their own,” she said. Kahindo said she had heard Ebola can remain in sperm between one and roughly three years.

Similarly, Edwige Kahindo is perplexed by conflicting data on the risks associated with breast milk.

“I didn’t know what to say or where to start,” the 78-year-old volunteer told TNH. She has heard that a woman’s breast milk can remain positive for Ebola anywhere between 16 and 500 days.

Health workers and others want more research into how Ebola is transmitted and into how much of a risk sex or breastfeeding can be. But they also acknowledge the challenges in the latest outbreak.

“Not only do we need to prove that the virus exists,” said Rigo from International Medical Corps, “but also to prove the virus can contaminate.”

sm/pd/ag