Nearly one million Ukrainian refugees live in Poland, 41% of them school-age children. Two years after Russia launched its attempted full-scale invasion of Ukraine, they are facing destabilising and pressing questions: How much of a new life should they build; and when – if ever – will they be able to return home?

The war has settled into a grinding stalemate in eastern and southern Ukraine, punctuated by periodic Russian missile barrages throughout the country. Out of a population of around 37 million, some 14.6 million people are estimated to be in need of humanitarian assistance and 3.7 million are internally displaced. Another 6.5 million Ukrainian refugees have been recorded around the world.

In Poland, about half of Ukrainian refugees say they want to return home after the fighting ends. In the meantime, Polish institutions are trying to adjust to hosting Ukrainians longer-term.

Dr. Anna Parkhomenko, 42, and her three children are some of the many Ukrainian refugees still figuring out how to navigate their new lives while contemplating when they will be able to return to Ukraine – and whether they will still want to when that time comes.

On 24 February 2022, when Russian missiles began raining down on Ukrainian cities and Russian troops began pouring across the country’s border, Parkhomenko and her children were jolted out of what now seems like an idyllic life on the outskirts of the eastern city of Kharkiv, about 30 kilometres from the Russian border.

After beating back breast cancer in 2020, Parkhomenko learned to be grateful for every minute. She had a rewarding job running the physical therapy department at a hospital in Kharkiv. Her children were always signed up for activities: chess, English lessons, gymnastics, martial arts. Her father and brother would help out when asked, and the father of her children – her ex-husband – would take the kids for weekends in the city centre.

When the children returned home to their apartment, they would be met by their big-eyed dog, Shauna, and a grey tabby cat, Seryy. In the summers, they went to Parkhomenko’s family dacha – a country house that generations of her relatives had been going to since 1887. There, the children played around roses and apple trees planted by her parents, while she and her brother tended to honeysuckle and grapes in the garden.

“We had everything,” Parkhomenko recalled.

When rockets started pounding their neighbourhood in February 2022, Parkhomenko hid briefly with her children in the corridor of their apartment building before rushing to the bomb shelter at the hospital where she had learned to practice medicine.

After 10 days in the shelter, Parkhomenko made the decision to leave. Like millions of others, they made the long trek across to the Polish border. The exodus was predominantly women and children, because men of military age were barred from leaving. Parkhomenko’s father, her brother, the children’s father, and their pets all stayed behind.

In Poland, the family moved from place to place, staying in an emergency shelter, then the apartment of a Polish volunteer, then a hostel. It took over a year for them to settle into one bedroom of a shared apartment on the outskirts of Warsaw where they now live.

Two years after coming to Poland, Parkhomenko doesn’t want to focus on what she has lost. “It’s a sin to complain about something when everything is okay, [when] you’re given the opportunity to live in safety,” she told The New Humanitarian.

However, for Parkhomenko and many of the millions of other Ukrainian refugees, the future remains an open question.

A shifting response

By September 2022, more than 1.3 million Ukrainians had registered for temporary protection in Poland under an EU directive that automatically granted them – unlike other refugees – the right to live, work, and access services.

Around 65% of Ukrainian refugees in Poland have now found work, while their number has dropped and stabilised at a little under a million. Some decided to return to Ukraine to reunite with family members. Some moved to other EU countries where they hoped to find better opportunities. Others swapped their temporary protection status for student or employment visas they hoped would give them a more stable future in Poland.

In 2022, Poland’s right-wing government welcomed Ukrainian refugees with open arms, driven in part by a shared history and fear of Russian expansion. But by 2023, the Polish government began to clash with the Ukrainian government over contested versions of history, agricultural exports, and more.

In the lead-up to elections last October, the then-ruling Law and Justice party – and other political groups further to the right on Poland’s political spectrum – tried to capitalise on anxieties about the impact of hosting Ukrainian refugees on the Polish economy and social services. Public support for hosting Ukrainians dropped from 94% in March 2022 to around 65% in September last year.

“Long term, collective shelters are not a good thing. It creates this environment from which it’s very hard to leave, it's very hard to move forward, and it’s easy to sink into despair.”

The Law and Justice party also signalled financial support for Ukrainian refugees would wind down by March of this year. But they lost out to an ideologically diverse coalition government led by veteran politician Donald Tusk. The new government has renewed Ukrainians’ protection status until March 2025.

While most Ukrainians have now settled into their own apartments, Agnieszka Nosowska, grant coordinator for the Polish Center for International Aid (PCPM) charity, said about 44,000 still live in collective shelters – the first point of refuge for millions in early 2022. Those still in the shelters are some of the most vulnerable, including disabled people, the elderly, and those with serious medical conditions, according to data from the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR.

“Long term, collective shelters are not a good thing,” Nosowska told The New Humanitarian, pointing to risks of sexual abuse and violence. “It creates this environment from which it’s very hard to leave, it's very hard to move forward, and it’s easy to sink into despair.”

Many refugees in Poland return to Ukraine for visits to see family, check on property, get important documents, or access healthcare. But on returning to Poland, a relatively high proportion (18% in 2023) found themselves dealing with legal and regulatory problems linked to their protected status, according to a UNHCR report.

Whatever lies ahead, the initial crisis stage of the refugee response in Poland has passed.

“We are definitely in a different phase right now,” said Nosowska, adding that the priority now is to focus on longer-term integration projects rather than just meeting Ukrainians’ immediate needs.

Schools are key

As the refugee response in Poland shifts to a longer-term phase, some institutions are trying to find ways to integrate Ukrainians without usurping their identity. It’s an issue that is particularly sensitive for Poland, a nation that takes pride in rebuffing the many historic attempts from Germany and Russia to make Poles more “like them”.

Activists warn the Polish state not to flip the script or try to “Polonise” Ukrainians, forcing them into Polish institutions. The refugee response, they say, needs to ensure that young Ukrainians can join Polish communities without losing a national identity that Russia is trying to destroy.

Given the proportion of children among Ukrainian refugees, schools are one of the key institutions where this tension is playing out. While 173,000 Ukrainian students were attending Polish schools as of October 2023, according to the Ministry of Education, that’s less than half of the total number of Ukrainian school-age children in the country.

Amnesty International says Poland isn’t keeping track of the number of children who study remotely in the Ukrainian education system instead of attending Polish schools, or of those who do not study at all. This is not just an issue in Poland: 44% of Ukrainian refugee families report at least one school-age child still not registered for school.

“Quite a lot may not be getting any education at all,” said Zofia Grudzinska, a prominent education activist in Poland. “But we have no way of knowing that for sure.”

Many young Ukrainians are doing double duty, juggling a full day of Polish school in person and then remotely studying in the Ukrainian system in the evening. Polish schools have hired Ukrainian educators as intercultural assistants to help ease Ukrainian children into the school system.

One NGO school, located in a converted floor of a Warsaw office building, is experimenting with teaching the Ukrainian curriculum in person, with additional courses in Polish and English. At the school, run by the Polish Center for International Aid, students attend classes from 8am until 6pm. The longer day, teachers say, allows them to catch up in Polish. It also helps refugee parents with childcare.

When students graduate, they will be awarded Ukrainian diplomas that allow them to continue their studies in Poland, Ukraine, or anywhere that honours a Ukrainian baccalaureate degree.

But it’s a solution that’s difficult to scale up. Unlike many other private Ukrainian schools in Poland that charge tuition, this one is free, thanks to corporate donations. However, the school, which has only been open for a year, already has a 220-person waitlist.

Sasha, 16, is one of the school’s star students. For him, being around teachers and students who know what he has been through makes the place feel more like home. So much in Warsaw is different from his hometown of Kyiv. But here, at least, the expectations, the language, and the grades are familiar.

“I think I will go to a Polish university, but I studied in a Ukrainian school for the whole of my life, so I think I need to finish in a Ukrainian school,” he told The New Humanitarian.

“Everything is okay. But I just want to return home.”

After class, he plays the Counter-Strike video game online, chatting with friends in the Warsaw home where he lives with his grandfather. Many of his friends are still in Kyiv. His whole family fled the city to Germany after the war started, but they hated it and moved to Poland. Eventually, his parents returned to Kyiv while he and his grandfather stayed.

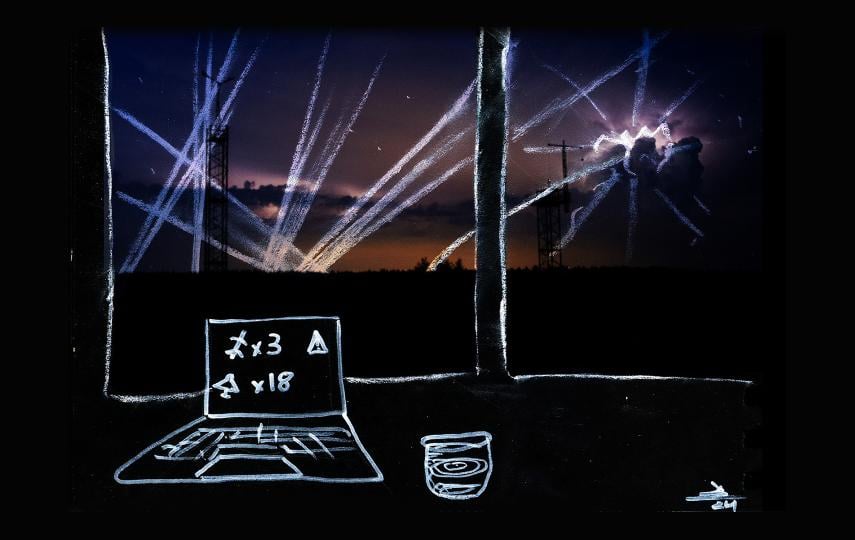

Sasha visits his parents in the Ukrainian capital on the holidays, which seems normal until it isn’t. A few days after Christmas, he was on his way back to Poland when Russia let loose a new barrage of rockets all over the country. Sasha returned safely. “I think I’m a bit lucky,” he said.

Sasha’s English teacher, Yulia, has not been so fortunate. Her hands shook as she spoke about living under Russian occupation with her daughter before fleeing Kherson, which was occupied for more than eight months. Yulia asked not to use her last name for her family’s security because they still live in Kherson.

“I like Poland. I like everything here. Good people. Everything is okay,” Yulia said. “But I just want to return home.”

But that is not possible. Kherson is still on the front lines of the war, with fighting raging nearby. Yulia’s daughter is also still afraid of loud noises. She is studying part time at the school, and Yulia wants to make sure she’s safe.

Weeks to months, months to years

Parkhomenko and her children can’t pinpoint when exactly their ideas about staying in Poland changed.

At first, the family kept hoping the war would end and they would be able to go home. But month by month that hope became more and more elusive. Only 40 kilometres from the Russian border, Kharkiv has remained a frequent target of shelling and drone strikes, one of which killed six children just last month.

In the residential neighbourhoods of Warsaw where the Parkhomenkos ended up, Poles have pitched in to help and make them feel welcome. Artem’s friend Szymon and his parents invited them for holiday celebrations and brought over food. The first person they stayed with helped sign the children up for school.

As the months have turned into years, the family has started to settle in. Potted plants now dot their new home – ficus, stone rose, and parlour palm. This spring, they will grow cucumbers on the balcony.

Parkhomenko still calls her ex-husband and her father all the time to ask about Ukraine, and Artem and Arina also study Ukrainian online at the end of their school day. Parkhomenko doesn’t want them to forget their language or where they came from.

When the war finally ends, the four will vote on whether they return or stay. But for now, “we are focused on living here,” she said.

Edited by Tom Brady and Eric Reidy. With reporting support from Mariusz Cieszewski and Szymon Gontarski.