Uprooted by fighting nearly three years ago, Hagos Gebremedhin and his family live in a classroom of a school in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region. It is a cramped, airless space, heavy with the smell of stale food, infested with bed bugs, and shared by more than 50 people.

In total, there are over 7,000 displaced people squatting in the school’s classrooms and play areas, living on top of each other and desperately waiting to go home.

These days, there is little to eat. Unable to farm their land, the camp residents relied on food delivered by aid agencies. But none has arrived since February following the discovery of a huge scheme to steal donated grain, which prompted a drastic decision by the UN and the United States to halt all food aid to Ethiopia in June.

“Sometimes we eat two flatbreads a day, sometimes one, and sometimes nothing,” said Hagos. Across Tigray, hundreds of people have died of hunger, with the aid pause hitting the region’s one million displaced people especially hard, according to local officials.

Roughly half of these displaced people, including Hagos and the other residents of the school, are from western Tigray, a fertile patch of land bordering Sudan. Western Tigray was once renowned for its gold deposits and sesame crop, but today it is best known as the site of some of the worst war crimes of the recent civil war in northern Ethiopia.

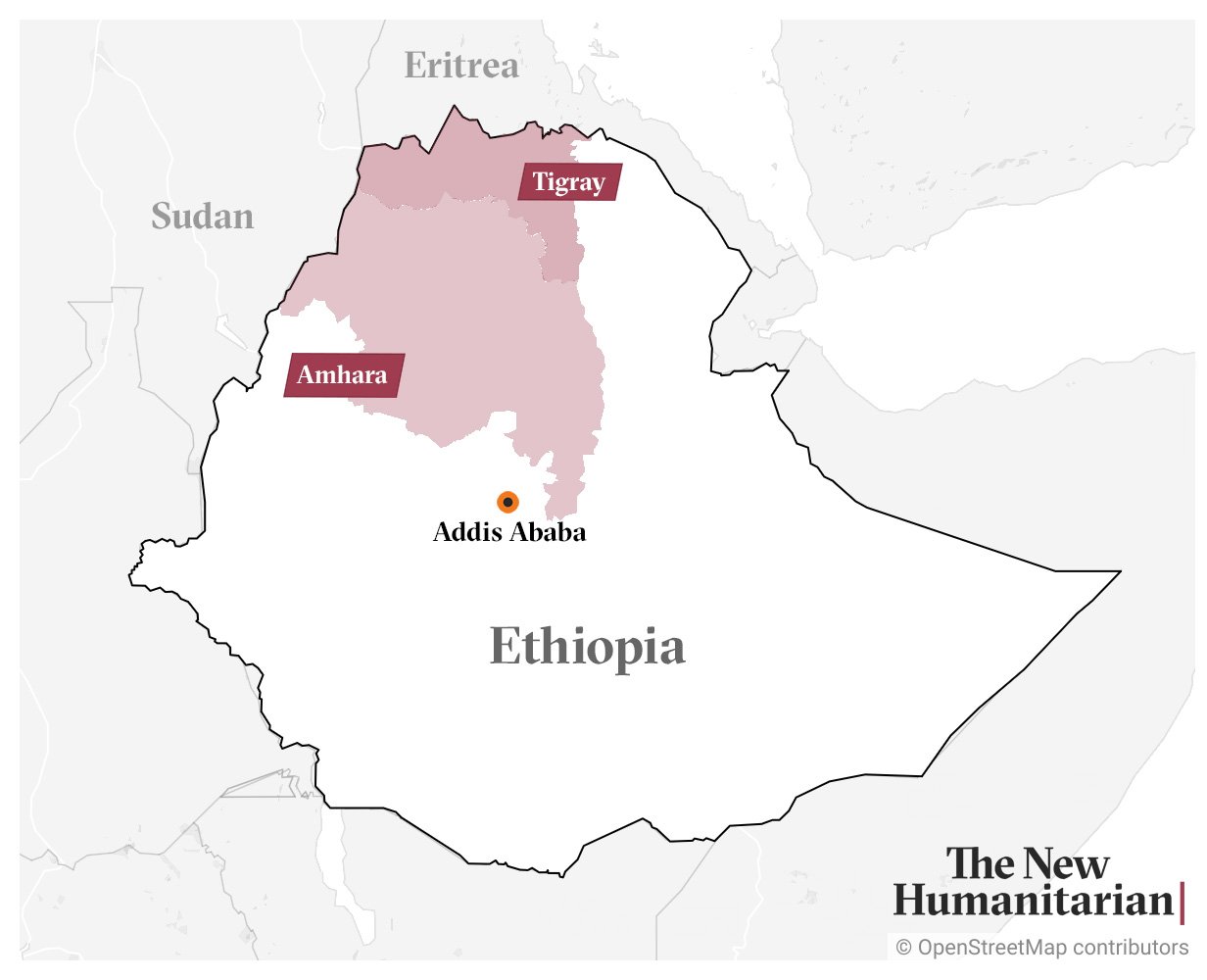

A dispute between Tigray and the neighbouring region of Amhara over the territory was a key issue underpinning the two-year-long conflict. Nearly a year after a ceasefire ended the bloodshed, its status is still unsettled and its former residents are in limbo, stuck in shabby displacement camps with practically no aid and unable to return.

Historical dispute

Under Ethiopia’s federal structure, which divides the country into states based on language and ethnicity, western Tigray is part of Tigray. However, it is also claimed by the Amhara, Ethiopia’s second-biggest ethnic group, who call it Welkait.

A foreign researcher, who asked not to be named so they could speak freely, pointed out that this claim over western Tigray is relatively new, having emerged from the anti-government protests that gripped Ethiopia in 2015-2018. That upheaval seeded a new Amhara nationalist ideology, to which the contested territory is central.

The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), Tigray’s ruling party, which fought the recent civil war against the federal government, first occupied western Tigray in the 1970s during their insurgency against Ethiopia’s former communist junta.

The party went on to dominate the ruling coalition that introduced the current federal system, which formally granted the territory to the Tigray region in 1995. The TPLF was eventually forced from power by the protest movement in 2018.

In the decades and centuries before 1995, western Tigray was part of various regions at different times, as Ethiopian rulers introduced their own administrative configurations. Supporters of the Tigrayan claim to the territory cite maps, treaties, and even poetry stretching back to the 17th century to show it has historically had a Tigrayan majority.

‘Ethnic cleansing’

When war broke out between the TPLF and the federal government in November 2020, the Amhara region’s paramilitary force and an Amhara militia called Fano annexed western Tigray. It is currently governed as a new zone of the Amhara region referred to as Welkait-Tsege-Setit-Humera, after its four component subdistricts.

These forces also seized parts of southern Tigray, another disputed area, which the Amhara also still control and refer to as Raya.

The Amhara occupation of western Tigray has been marked by extreme violence. In the early weeks of the war, thousands of people fled with tales of door-to-door killings, rape, and looting. One displaced Tigrayan woman told The New Humanitarian how Fano militiamen tied up her husband and shot him in Humera, a town on the Eritrean border. Another recounted escaping barefoot along a road littered with her neighbour’s bodies.

At this time, huge numbers of ethnic Tigrayans were loaded onto buses by Amhara forces and dumped at the river that separates western Tigray from the rest of the region. Eviction notices were posted on the doors of Tigrayans' homes, warning them to leave.

“These widespread and systematic attacks against the Tigrayan civilian population amount to crimes against humanity as well as war crimes.”

These actions amounted to “ethnic cleansing”, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in March 2021. In total, hundreds of thousands of Tigrayans were forced from the area, with most now scattered across Tigray, and some 60,000 stuck in camps in Sudan.

A joint report published in April by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch gave the most detailed picture yet of this campaign of expulsion. The rights groups said some of the abuses were done in coordination with troops from Eritrea that remain in western Tigray and other border areas. Eritrea is an ally of Ethiopia’s federal government.

“These widespread and systematic attacks against the Tigrayan civilian population amount to crimes against humanity as well as war crimes,” the rights groups said.

Thousands of ethnic Amharas have been settled in the area, many of them given the empty former homes of Tigrayans. Land was also sold off to businessmen from Amhara.

Despite the ceasefire between the TPLF and the federal government, forced expulsions and arbitrary detentions against Tigrayan civilians are still happening in western Tigray.

“Life for Tigrayans is very hard,” said a man interviewed by The New Humanitarian in the Humera district of western Tigray. He said Tigrayans face almost daily harassment from machete-wielding militia in the area. Another resident said Tigrinya, the language of Tigray, has been banned in schools.

Two other Tigrayans, expelled from the area since the peace deal, said they were detained by Amhara forces because of their ethnicity, and that while they were held, the fighters deprived them of food and subjected them to regular beatings.

All four requested anonymity, citing fears for their safety.

The violence was not all one way. Tigrayan rebel forces were accused of killing Amhara labourers in the western Tigray town of Mai Kadra in November 2020 and also committed alleged abuses against civilians when they launched an offensive into the Amhara region in the second half of 2021.

Unsettled status

Amhara forces did not sign the ceasefire that ended the war last year. The deal does not mention the contested territories directly or contain provisions for resolving their status.

However, the deal does aim to “restore the constitutional order disrupted due to the conflict in the Tigray Region”, and elsewhere it commits the TPLF and the federal government to respecting Ethiopia’s constitution.

These passages mean the deal requires the return of western and southern Tigray, a senior TPLF member, who asked not to be named, told The New Humanitarian. That is because the constitution says border disputes can only be settled by agreements between states or – if an agreement is not reached – by the upper federal parliament based on settlement patterns and residents’ wishes.

In other words, annexing territory through violence is unconstitutional. So if the constitution is to be respected, the territories must be restored to Tigray.

This interpretation of the deal is disputed. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, for example, has said resolving the status of the land is beyond the scope of the ceasefire and suggested a referendum. This would reflect precedents in southern Ethiopia, where residents have voted recently to form their own states.

“We went to South Africa not to decide to have Wolkait in Amhara or Tigray, the Pretoria [agreement] has not that power… We agreed we should solve it based on Ethiopian law,” Abiy said in November. “People should be given the chance... to get democratic opportunities. Only through that can we get a solution.”

Yet little thought has been put into what this referendum would look like. “It doesn’t really look like the federal government has a plan,” said a Western diplomat, who didn’t want to be named so they could speak freely on the sensitive issue.

“The Amharas don’t want a referendum. They feel it is a betrayal. The PM was saying during the war that these contested areas are Amhara.”

The Tigray authorities say the territories should be restored to them and all the displaced Tigrayans returned before a vote is held. “Otherwise, it would set a very dangerous precedent,” noted the senior TPLF member. “It would mean other states could take any territory by force and then hold a referendum to formalise it.”

He argued that it was the federal government’s responsibility to ensure the lands are returned: “We are waiting for them to live up to their obligations,” he told The New Humanitarian. “It is not very complex.”

Diplomats fear the dispute over western Tigray could reignite the war if it is allowed to drag on and if the TPLF feel they have no option but to take it back by force.

These fears were heightened last month when fighting erupted across Amhara. The immediate spark for the violence was a plan to disarm the region’s armed forces: But concern that Abiy may hand the land back to Tigray is also fueling the unrest.

“The Amharas don’t want a referendum,” said an Amhara official. “They feel it is a betrayal. The PM was saying during the war that these contested areas are Amhara.”

These Amhara concerns were further stoked last month when the defence minister, Abraham Belay, who is Tigrayan, described the Amhara administrations in western and southern Tigray as illegal and said that “work is in progress” to dismantle them.

“They will be freed from armed forces apart from federal security forces, and the Ethiopian Defence Force will execute this responsibility,” said Abraham, uttering the strongest remarks yet by a federal official on the contested territories. Such a move would almost certainly spark serious clashes between the Amhara and federal forces.

Deepening humanitarian toll

As the dispute rumbles on with no resolution in sight, western Tigray’s displaced population face an impending humanitarian disaster. Without aid or access to their old farms, most are unable to feed themselves and many are resorting to begging.

Last week, the regional government started returning people to areas that are deemed safe, but the process excludes western Tigray.

“Until the area is safe and under our administration, we cannot return displaced people to the west,” Mulugeta Debalkew, the regional official overseeing the process, told The New Humanitarian. “They are expected to return back eventually, but at the very minimum they first need security and humanitarian assistance, which is not available there.”

Beyenesh Tadesse, who lives in the same displacement camp as Hagos, said conditions are desperate. Illness already claimed her husband last year. Now her five children are growing increasingly weak from hunger.

“I plead with the world to help us,” she said. “We have nothing left, nowhere to sleep, and nothing to eat. We are desperate. Why does no one care?”

Edited by Obi Anyadike.