Sudanese civil society groups are playing a pivotal role in documenting human rights abuses committed during 10 months of conflict, even as volunteers risk being arrested by the warring parties and are struggling with a month-long internet blackout.

Youth groups, legal associations, and civilians acting in a personal capacity have all been involved in cataloguing the human rights impacts of the conflict that commenced in April 2023 and sets the army against the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

“Documentation is a pathway to justice,” Noon Kashkoush of the Emergency Lawyers, a legal group monitoring abuses, told The New Humanitarian. She said she hopes the evidence her group has gathered will be used one day in the Sudanese justice system.

Sudan’s conflict was triggered by a disagreement over plans to merge the RSF into the army. However, the war echoes a longer struggle between military and political elites drawn from groups based in the centre, and challengers from marginalised peripheries.

The power struggle has produced the world's largest displacement crisis, uprooting over eight million people, and threatens to trigger the largest hunger crisis too. Appeals last week for a Ramadan truce by the UN Security Council have been rejected by the army.

Access challenges for international aid agencies mean local mutual aid groups have shouldered the bulk of the relief effort in the most conflict-affected places. And likewise, civil society initiatives have carried the burden of human rights documentation.

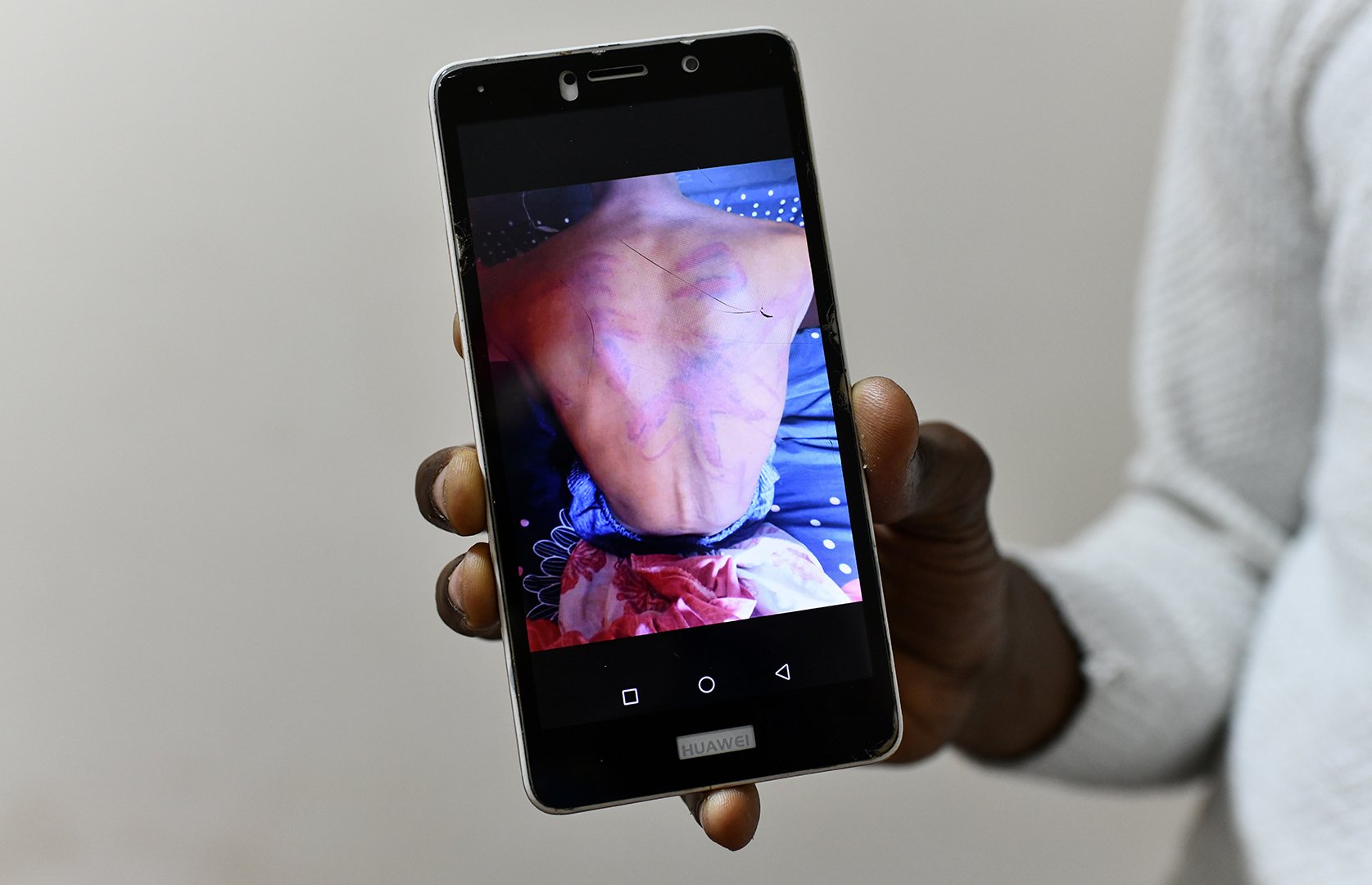

Despite the volatile security situation, local groups have led efforts to document sexual violence and killings, monitor ceasefire violations, track down missing persons, and report on the makeshift detention sites run by both the army and the RSF.

The findings of these civil society groups have fed into numerous human rights reports, including a detailed report last month by the UN, which charges both sides of the conflict of committing widespread abuses, some of which may amount to war crimes.

The report accuses RSF fighters of occupying residential buildings to shield themselves from army attacks, of massacring thousands of people in the Darfur region, and of committing extensive sexual abuse, including cases of rape and gang rape.

For its part, the army is accused of killing more than 100 civilians in airstrikes that were ostensibly targeting RSF positions but carried out in densely populated urban areas, or on public buildings including churches and hospitals.

The report also documents attacks on human rights defenders. It states that activists have been kidnapped and subjected to death threats and smear campaigns organised by army supporters, while several Darfuri rights monitors have been killed by the RSF.

Volunteer lawyers and youth groups

Many groups documenting rights violations were active during the 2018-2019 Sudanese Revolution that toppled dictator Omar al-Bashir, and during the protests that followed the 2021 army-RSF coup that ended the post-Bashir democratic transition.

Prior to the war, the Emergency Lawyers group was providing legal assistance to the families of pro-democracy protestors and activists who had been arbitrarily arrested, tortured, or killed by security forces.

Kashkoush said the group is now focused on war-related abuses, including the bombardment of civilian areas and the detention centres set up by the army and RSF in the capital, Khartoum, and the neighbouring cities of Omdurman and Bahri.

Kashkoush said the publication of the group’s reports and announcements have helped secure the release of hundreds of detainees – including some from the Emergency Lawyers network itself – though she described facing many difficulties.

“All of those documenting violations face the issue that movement on the ground is very challenging,” she said. “We depend a lot on open-source [information], such as video footage, and we work to verify it using witness statements.”

Another group involved in documenting abuses is the Youth Citizens Observers Network (YCON). It was established in late 2021 by volunteers wanting to shed light on violations committed against pro-democracy protesters and civil society activists.

After the current conflict broke out, the network relaunched its platform under an anti-war stance, according to one of the group’s volunteers, who requested to remain anonymous to ensure their safety.

The volunteer said YCON has observers across Sudan and releases monthly reports on the impact of the war and the human rights situation. It also monitored several army-RSF truces that were violated last year.

“In any given region, civilian monitors who are trained in documentation and verification methods are present on the ground and have a very wide network of connections,” said the volunteer. “Any event happening in a specific area, they would know about it.”

A businessman's broadcast

In cases where access to places affected by fighting has been too difficult for civil society groups, civilians already on the ground have taken it upon themselves to document what they are witnessing and publish evidence on social media.

When clashes between the RSF and the army first broke out in Khartoum, Hassan Abd al-Rauf, a local shop owner who ran a travel agency and a men’s clothing store, found himself caught in the epicentre.

Instead of escaping or complying with an RSF order that civilians should leave his neighbourhood, al-Rauf decided to stay, guard his properties, and offer assistance to others who were struggling to flee.

Walking through deserted streets, al-Rauf began recording live broadcasts on his Facebook page. His footage revealed the extent of the destruction and showed unarmed civilians who had been killed in the crossfire or targeted by snipers.

“When I started with the broadcasts, the aim was to connect people with what was happening on the ground and send photos [of the damage] back to the property owners in the area,” al-Rauf said in an interview after escaping Sudan for Qatar.

Two weeks after starting the broadcasts – which were getting hundreds of thousands of views – al-Rauf’s uploads suddenly stopped. He said he was captured by RSF fighters in the capital and held in a detention centre for 25 days.

“[The RSF] were certainly aware and it was the reason for my arrest,” al-Rauf said. “[One of my videos showed] a number of RSF vehicles after they had robbed the Bank of Khartoum and were hit by army aircraft.”

Security threats and a communication blackout

The volunteer at YCON said members of their group have faced harassment and the threat of detention from security forces as they attempt to move across different locations to document violations.

Similar threats were also described by a member of the Missing Initiative, a local group with a platform that lets people post information about missing people. The group has a Facebook page with hundreds of thousands of followers.

“On a personal level, I receive private messages that include threats and very bad language,” said the member of the group. “Before the war, [the military authorities] were trying to hack our page many times,” they added.

On top of the security risks, volunteers told The New Humanitarian they are also struggling with a nationwide communication blackout that began in early February and has been blamed on the RSF.

Kashkoush of the Emergency Lawyers group said her organisation is unable to receive daily updates about human rights abuses, and instead gets a flurry of reports during the brief moments when they have an internet connection.

Kashkoush called for an international investigation into the blackout, which she described as a “constitutional violation” and a “deliberate attempt by one or both sides” to restrict access to information and thwart documentation efforts.

“A prolonged internet blackout is synonymous with a humanitarian catastrophe on the ground, because the majority of the civilians present in areas of combat are completely dependent on mobile banking transfers to survive,” Kashkoush added.

The psychological burden

Documenting rights abuses has also had a psychological impact on volunteers, according to the member of the Missing Initiative, which was founded in 2019 shortly after the RSF killed over 120 pro-democracy protesters at a Khartoum sit-in.

The volunteer, who is based outside of Sudan, said the most difficult aspect of their work is delivering bad news to families when they learn that a missing person has been found dead.

During the first few weeks of the conflict, the Missing Initiative’s Facebook page was flooded with requests for information about people who had gone out to buy groceries or fuel and hadn’t returned.

Between April and August 2023, the volunteer said the group received over 600 reports of missing persons. They added that the group stopped publishing statistics when they realised the actual number of cases was likely much greater than those reported to them.

Despite the challenges the group faces, the volunteer told The New Humanitarian they are determined to keep the initiative alive, especially as the conflict slips out of international focus.

“The main reason I am doing this is because I am a defender of human rights,” they said. “This is a continuation of the work we began after the [2019 Khartoum sit-in] massacre, on the basis that, in the future, both sides will be held accountable.”

The volunteer from YCON shared a similar view: “The fundamental motivation that allows us to continue monitoring the situation… is that this will provide accurate, recorded information for the institutions that will later work on [justice].”

Edited by Philip Kleinfeld.