After vomiting blood and exhibiting fever – two of the virus’s telltale symptoms – the teenager had come to the Ebola isolation ward here in Yambio, a South Sudanese town near the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo.

But it wasn’t until he noticed Ebola posters hanging on the walls and medical staff in unusual scrubs that the shy boy – whose name has been withheld to protect his identity – realised why he had actually been confined. Nobody had thought to confirm it to him.

“Given the geographic proximity to the border with Congo, it’s most probably not ‘if’ but ‘when’ South Sudan will see an imported case.”

Lingering insecurity, a lack of funding, and issues with managing cases like the boy in Yambio are hampering efforts to prevent a possible outbreak of Ebola in South Sudan, according to health workers, government officials, and community leaders interviewed by The New Humanitarian.

With over 2,000 deaths in neighbouring Congo and at least four imported cases in recent weeks in Uganda, health experts say it is only a matter of time before the first cases emerge in South Sudan, where five years of conflict have left nearly 400,000 people dead, millions displaced, and brought an already weak healthcare system to its knees.

“Given the geographic proximity to – as well as population movements across – the border with Congo, it’s most probably not ‘if’ but ‘when’ South Sudan will see an imported case,” said Sudhir Bunga, South Sudan country director for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the US health protection agency known by the initials CDC.

Funding gaps

South Sudan’s health ministry officials, together with international and local partners, have been preparing for a potential outbreak since Congo declared its epidemic last August – 32 screening points have been established in border towns and almost 3,000 frontline health workers have been vaccinated.

The country ramped up surveillance at some of its busiest crossings after a 41-year-old woman was discovered with Ebola in June in Ariwara, a Congolese town just 43 miles (70 kilometres) from the border.

Dr. Ali Ahmed Yahaya, a programme manager at the World Health Organisation, said there has been “significant progress”, such as establishing a new health emergency centre and a laboratory to test suspected cases.

Yet, despite more than a year of planning and preparation, the country’s war-weakened healthcare system is still struggling to keep up.

“No amount of preparedness is adequate for the country, given the nascent public health infrastructure,” said the CDC’s Bunga.

A lack of funding is also hampering efforts, according to Richard Lako from the South Sudanese government’s Ebola task force – $12 million was requested for the current round of Ebola preparations, but just 38 percent of that has been received so far.

Leaning his elbow on the wooden barrier that separates the green zone from the high-risk red area, the 15-year-old South Sudanese boy timidly asked the question that had been troubling him for days: “Do I have Ebola?”

Members of a rapid response team – whose job is to identify and monitor cases – have left their roles because they are not being paid, Lako said.

The challenge of preparing for Ebola can be seen most clearly in places like Yambio – a rural, conflict-hit border town where nine suspected cases of the virus have been isolated since February, including the 15-year-old mentioned above.

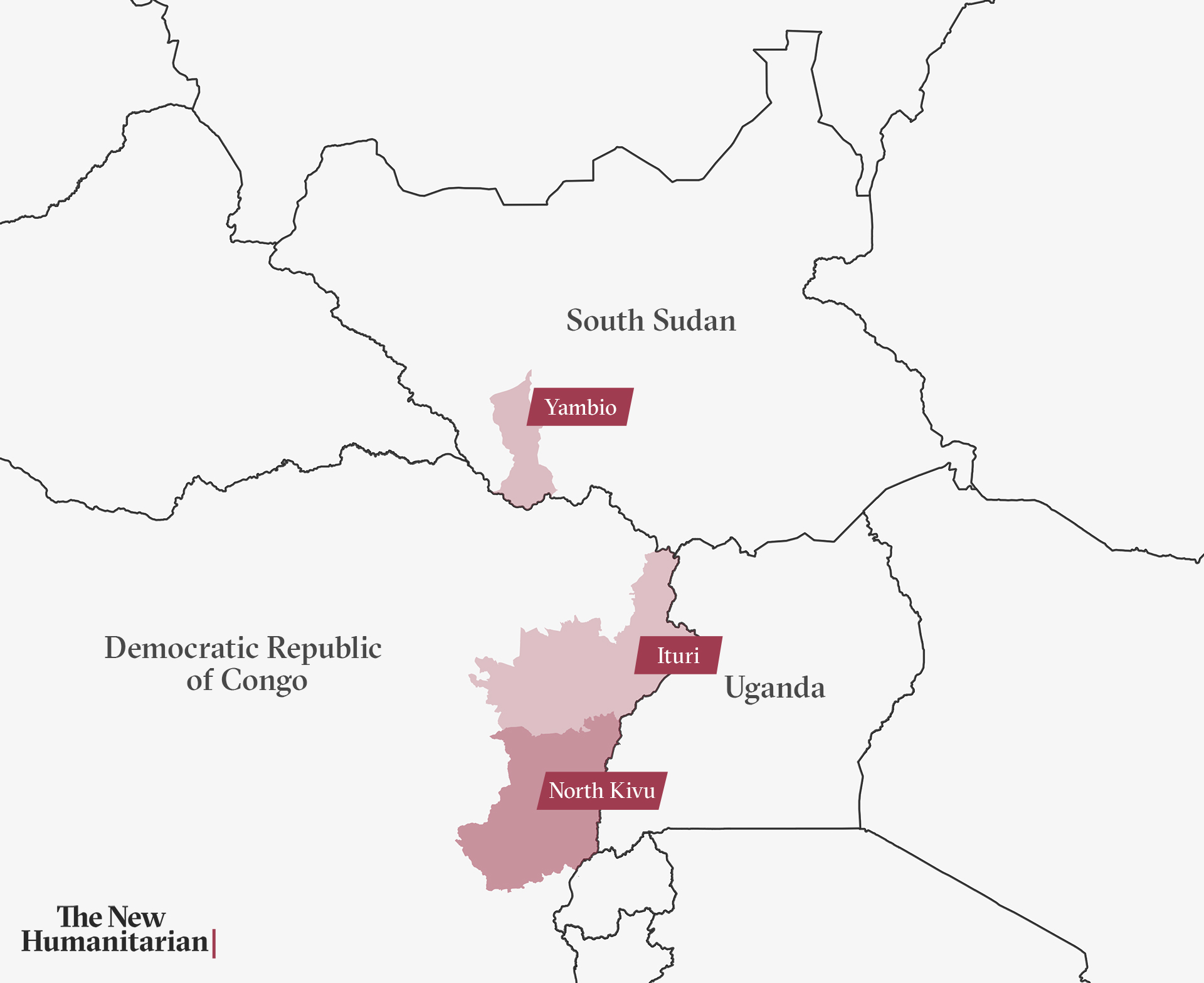

Insecurity from years of fighting has cut off direct access to neighbouring Uganda, forcing traders in Yambio to reroute through Congo’s Ituri province, which has seen more than 350 confirmed Ebola cases since the outbreak began in August last year. The majority of Congo’s more than 3,000 cases have been further south, in North Kivu province.

Poor case management

On a visit to Yambio last month, TNH witnessed a community struggling to prepare for the virus and health workers struggling to manage cases safely and effectively.

At Yambio’s Ebola isolation ward, four patients – two suspected cases and two contacts (people known to have had contact with suspected cases) – said it took around 24 hours for doctors to explain why they were being held in isolation.

A health worker involved in Ebola preparations, who wasn’t authorised to speak on the record, described the delay as “outrightly shocking”.

“Patients have a right to know why they are admitted, and they and their caregivers or family members must be made aware in real-time,” said the health worker. While doctors don’t want to panic people, there are ways to properly communicate the situation without hiding it from them, he added.

Patients suspected of having Ebola are also not being isolated properly.

After vomiting blood and showing signs of fever, 50-year-old John Henry said he spent a night at the state hospital in Yambio instead of being isolated, because there was no doctor on duty to tell them where to go. Henry tested negative for the disease, but if the results had been different more people would have been exposed to Ebola risk.

Changing behaviour

As the community in Yambio braces for Ebola, health workers and local leaders say they are stepping up efforts on community outreach and engagement.

Trying to lead by example, leaders bump elbows instead of shaking hands when greeting each other and have stationed hand-washing centres outside churches and schools.

“People have discovered it’s real and can kill you,” said Emmanuel Ezekiel, pastor of the Seventh Day Adventist Church.

Ezekiel said he has been giving seminars to the community since June, but despite his efforts people are taking time to adjust their behaviour.

In August one woman suspected of having Ebola fled Yambio’s isolation ward because she was scared, health workers said. Another woman’s dead body was carried from Congo and buried in the town without being properly tested for Ebola.

“The way we’re treating dead people is a nightmare for Ebola.”

While South Sudan’s government has banned the sale of bushmeat – a potential vector of Ebola – people are still finding “sneaky” ways of buying and selling it, added Joseph Salvatore, director for the humanitarian arm of the government in Gbudue state.

Salvatore said it is South Sudanese burial practices that concern him most. Ebola victims remain highly infectious even after death, yet local customs often involve people getting extremely close to the deceased, including lying beside or on top of them once they’ve passed away.

“The way we’re treating dead people is a nightmare for Ebola,” said Salvatore. “We love dead people more than the living.”

Compounding the burial practices issue are the porous borders and areas that still lack screening sites between Congo and South Sudan. After months of planning, even established screening points in the country aren’t always reliable.

Upon entrance into Juba’s international airport in April, while filling out the Ebola medical form, one aid worker – who asked not to be identified – decided to test the monitoring system by ticking yes to all the symptoms before scribbling “I have Ebola” at the bottom of the page.

The humanitarian handed the sheet to health workers. They let her through without question.

(TOP PHOTO: A presentation on Ebola awareness on 1 August 2019 in Yei, South Sudan.)

sm/pk/ag