Somali refugees have no good options any more. With Kenya vowing to close the Dadaab refugee camp within months and resettlement to the United States suspended, many will succumb to growing pressure to return home, where al-Shabab militants and a potential famine await.

Mulki Mahmood lives in a busy tenement block of two-bedroom apartments, narrow corridors, and billowing lines of washing in Nairobi’s working class suburb of Eastleigh.

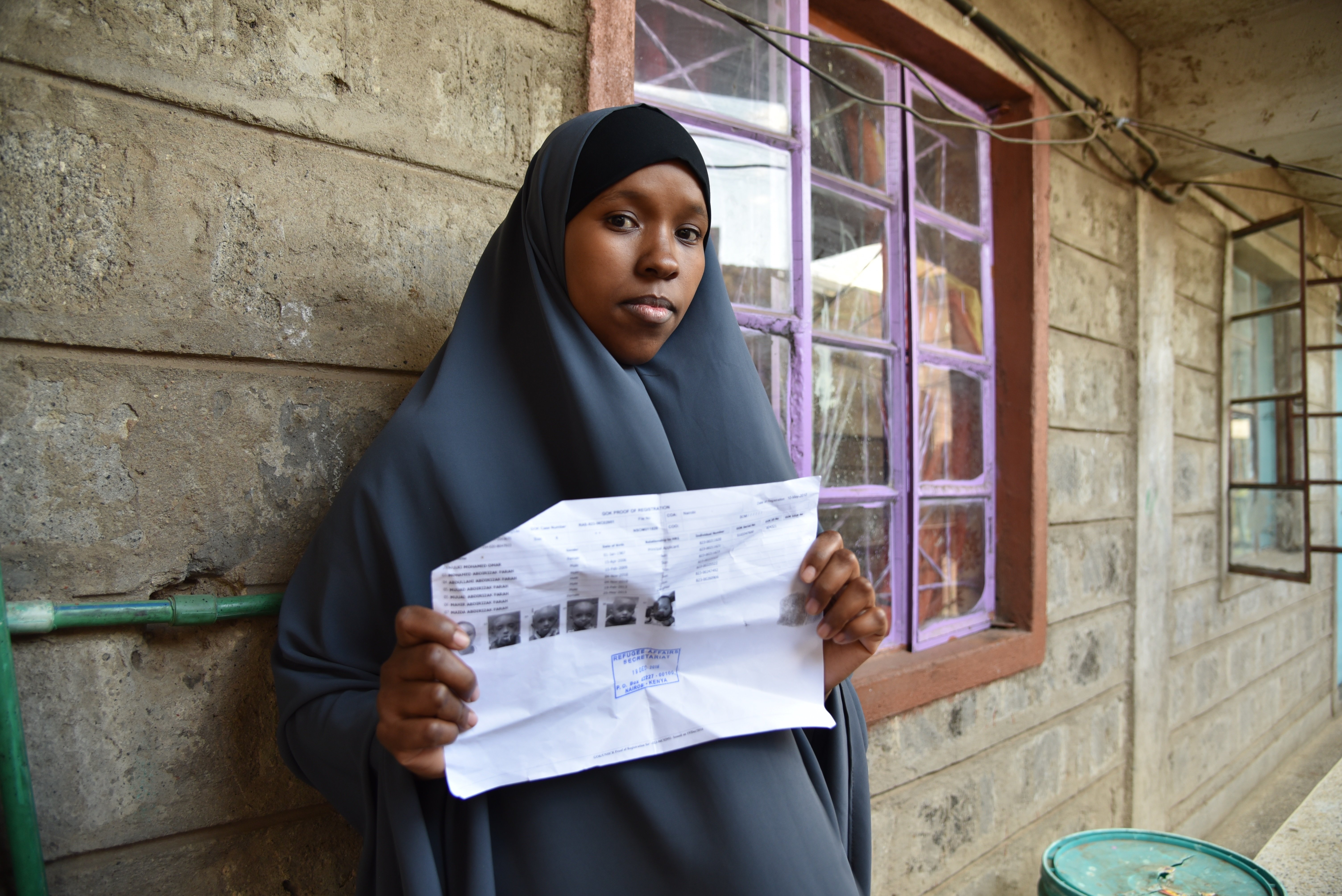

As a Somali refugee and single mum, life has not been easy. The one bright spot was that she had finally been accepted for resettlement in the United States, and was expecting to swap her down-at-heal neighbourhood, with its criminal gangs and hand-to-mouth existence, for a new life with her daughter in Ohio.

But US President Donald Trump’s executive order on Friday, suspending refugee admissions for four months, has put Mahmood’s plans – like so many others – on hold.

“We’ve been vetted, and vetting is good,” she told IRIN. “I’m just asking for our humanity to be respected, because we are not related to any group causing mayhem or instability.”

Mahmood, 30, has twice been a refugee. First as a child in 1992, escaping the start of the Somali Civil War. Then in 2003, after she had returned home, she was forced to flee again to Kenya, ending up in the Kakuma refugee camp.

Respect

Mahmood got married in Kakuma, but as soon as she gave birth, her husband divorced her. She had little choice but to come to Nairobi to look for work to support her child. She got set up selling snacks on the streets; always having to dodge the police demanding money, the threat being they can send you back to Kakuma.

Mahmood has also survived rape, attacked by a man until she fainted, according to the medical report from the Médecins Sans Frontières clinic she visited. All she wants, she says, is a future for herself and her daughter.

“Men here don’t respect you as a single mother, they misuse you,” she told IRIN. “America is a great country. People’s rights and women’s rights are respected. I can educate my daughter and maybe get married.”

Mahmood has been chasing resettlement for nine years. “I used to sleep outside the [UN refugee agency] UNHCR office in Westlands,” she laughed, her niqab off her face, relaxed. “Now my resettlement process is due, Don… I can’t even say his name, has put me on hold!”

Mahmood has a resettlement number but has not been given a travel date, so she is yet to properly begin the process of packing up her life in Kenya.

Vulnerable groups

Omar Hassan Ibrahim, on the other hand, was due to have flown out last weekend, hours after Trump’s executive order was published. He and 140 other Somali refugees are now stuck in a transit centre in Nairobi run by the US State Department. What happens next is far from clear.

“I don’t know what will be my future,” 28-year-old Ibrahim told IRIN over the phone, describing resettlement as his “one and only chance”.

The transit centre is only meant to hold people for a couple of nights. UNHCR and its partner, the International Organization for Migration, are scrambling to find a way to safeguard the most vulnerable protection cases, including LGBT refugees.

“Our staff are more than a little concerned. They know these [resettlement] cases really well,” said IOM spokesman Leonard Doyle. “We’re working closely with UNHCR to ensure those that can’t leave [the centre] are given all the support they need.”

Ibrahim assumes he will probably have to go back to the Dadaab refugee camp, in Kenya’s remote northeast, where he has lived since 1992. That will be a psychological as well as a material blow.

People about to be resettled have typically given up their shelter, sold off their possessions, taken their children out of school, said their goodbyes and mentally checked out. They will now have to reconnect with a bureaucracy they thought they had escaped, including reapplying for the all-important ration card.

The United States is the world’s top resettlement country. Somalia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo represent the bulk of the refugees from Africa accepted by the US. In 2015, it took in roughly 9,000 Somalis. In 2016, it planned to resettle 3,000 Somali refugees.

Trump’s executive order chimes with the position of governments like Kenya. The country has been a generous host, but the welcome towards Somalis soured after a series of high-profile attacks by al-Shabab jihadists on a shopping mall in 2013 and a university in 2015 that killed at least 215 people in total.

Pressure from Kenya

There is no public evidence that the attacks were planned in Dadaab, a sprawling refugee complex that was once the world’s largest. But the government has set a final deadline of May for the camp’s closure and the repatriation of 261,000 refugees living there.

It has piled on the pressure, revoking the prima facie refugee status for Somalis and disbanding the Department of Refugee Affairs. It has also pushed UNHCR to speed up a voluntary repatriation programme, which human rights groups condemn as being far from voluntary.

With food rations repeatedly cut in Dadaab, the generous repatriation package being offered to refugees is a real lure. But they are returning to an insecure country, where social services are absent, and returnees are typically stuck in crowded IDP camps in the southern city of Kismayo, unable to reach their home regions because of al-Shabab.

“We have been caught between two rocks, or even three,” Yakub Abdi told IRIN over the phone from Dadaab’s Ifo camp. “Life in the camps has been deteriorating over the past years: food insecurity, poor health facilities, and constant threats to close the camp by Kenya. And now comes Trump.”

His colleague, Ahmed Dahir, said that despite serious misgivings he would go back to Somalia after 25 years in Dadaab. “The only hope I had was to be resettled in the US, and that has now shut down.”

Drought crisis

But a graver risk even than that of al-Shabab harassment and recruitment is a drought under way in Somalia that bears all the hallmarks of the 2010-2011 catastrophe that led to the deaths of nearly 260,000 people, including 133,000 children.

An estimated five million Somalis – 40 percent of the population – are in need of food aid as a result of what is now the fourth consecutive drought in parts of southern and northern Somalia.

The UN and the Famine Early Warning Systems Network are sounding the alarm. If there are poor rains again in the March/April season, if people’s purchasing power (as is likely) remains weak, if al-Shabab blocks humanitarian access, then “famine would be expected”, warns FEWSNET.

In South West State, people are already abandoning their homes for IDP camps in the main town of Baidoa in search of food. World Vision is reporting similar “distress migration” in the Mugud and Bari regions of Puntland in the northeast.

“If it goes to famine, where are these people going to flee?” said Human Rights Watch researcher, Laetitia Bader. “Will they have to avoid Dadaab, which was where many sought refuge in 2011? Will they have no option but to end up in the dangerous and poverty-stricken displacement camps in Somalia?”

“Somali refugees in Dadaab are increasingly trapped,” said Bram Frouws with the Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat. “There’s nowhere for them to go.”

They are squeezed by the Kenyan government; the EU has also struck a deal with Sudan to stop overland migration flows to Libya and Egypt; South Africa, previously a regular destination, has announced stricter migration policies; and Yemen, also a historical bolt hole, is now off the map due to its own conflict and deepening humanitarian crisis.

There have been anecdotal reports of refugees in Dadaab buying Kenyan IDs and heading to neighbouring Uganda, which has a far more liberal refugee regime. But Uganda is already struggling to shelter some 580,000 South Sudanese refugees who have entered the country since 2013.

“My best guess is that those who have money have already tried to leave,” said Frouws. “Those without money or opportunities are either stuck in Dadaab for now, and must wait and see [whether the government follows through with its closure threat], or take the return packages and return to Somalia.”

Trump, Kenya, drought – it’s all “extremely negative”, he said.

oa/ag

(Additional reporting by Abdullahi Mire)

TOP PHOTO: Somali refugees in Kenya can only hope the resettlement ban will be lifted. CREDIT: Obi Anyadike/IRIN