There have been five Ebola outbreaks in Uganda over the past 14 years; these have been quickly contained thanks to a combination of epidemiological luck and a well-coordinated response system operating at several levels of the health service.

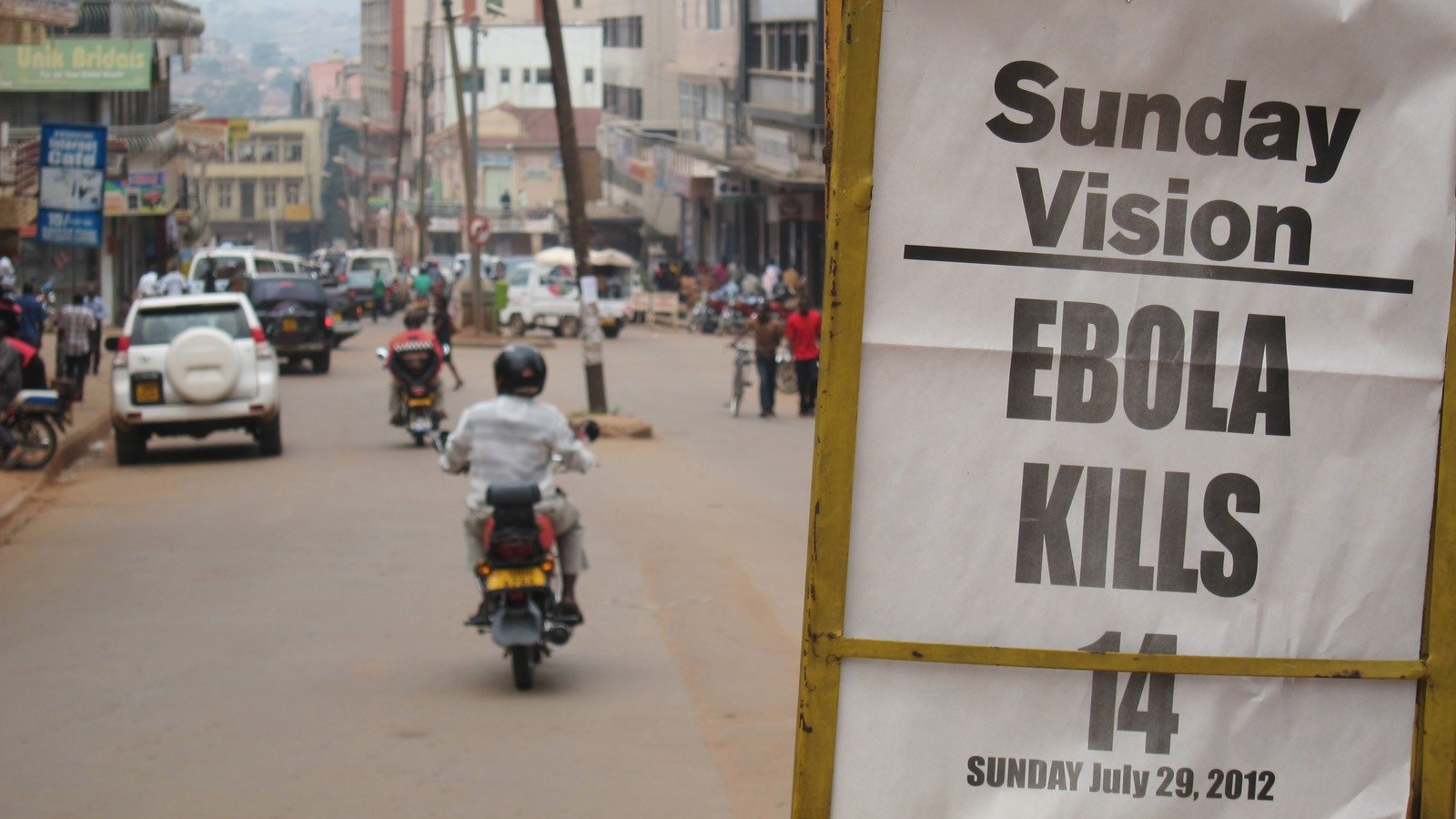

Uganda's first Ebola outbreak in the northern district of Gulu in 2000 infected 425 people and killed 224. The second outbreak in 2007 killed 37 people in the western district of Bundibugyo, and an outbreak in 2011 in central Luwero District killed one person. A July 2012 outbreak in the western district of Kibaale infected 24 and killed 17 people; and a December 2012 outbreak in Luwero killed four, according to the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

IRIN looks at how Uganda has dealt with the disease in the past.

Has Uganda been lucky?

"Uganda has historically handled these [Ebola] cases very well. If there is a suspected case of Ebola, local health officials follow a process for investigating and reporting a suspect sample through DHIS2 [the District health Information System]," Trevor Shoemaker, an epidemiologist at CDC's Viral Special Pathogens Branch in Uganda, told IRIN.

"True, Uganda has been able to contain several epidemics in the past of Ebola and has done it without major spillover at least within the country or the region," Freddie Ssengooba, Associate Professor, Health Systems Management, Makerere University School of Public Health, told IRIN.

"Uganda has been lucky. Most of these epidemics have been rural and is likely to be containable through gazetting and quarantining within those areas. But in urban settings, the whole issue of control and containing epidemic can be difficult. It's very hard for those people to be contained. They will definitely run through and get onto the bus and before you know it, they are all over the country and epidemic spreads faster," he said.

"West African countries have been unlucky that most of the epidemic and transmission has been through urban centres. Most people run to the airport, bus stops and quickly travel to the next town either to be near family or move to different countries to find better health care. So in that process the whole epidemic has almost been internationalized due to connections between towns and transport channels."

How does the response process work?

In Uganda, someone from the Village Health Team (VHT) or a district health worker notifies the district surveillance team or health officer of any suspected Ebola case.

The health officials assess the patient to make sure they meet the clinical criteria for a suspected Viral Haemorrhagic Fever [VHF] case, and if they do, that patient is transported to a local medical facility, a blood sample is taken, and the patient isolated from other patients until confirmatory laboratory testing is completed.

The District Health Officer then sends an alert to the national level through the DHIS2 electronic notification system. The sample is registered and sent to the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) and CDC in Entebbe for testing.

"A system has been put in place in Uganda to notify, collect a sample, send it for testing and then report results within 24-48 hours," Issa Makumbi, head of epidemiology and surveillance in MoH, told IRIN.

"What is different about Uganda's response to outbreaks of Ebola is that there is heightened sensitivity regarding reporting of suspected VHF (viral haemorrhagic fever, of which Ebola is a type) and Ebola cases and these are therefore typically reported and tested within days, not weeks," CDC's Shoemaker, told IRIN.

"With CDC's support, Uganda now has the ability to test samples within 24-48 hours of receiving them and this allows a response team to be deployed to the [affected] district to begin a rapid response quickly. This time factor alone can greatly reduce the total number of cases because you can rapidly identify new cases and monitor contacts," he said.

"There has been galvanized effort in terms of diagnosis by our partners. Previously, it would take us weeks before we can conclude on suspected case. But now, if we get a case, we get the results within six to 48 hours. So we can tell people this is Ebola or not because we have gained the testing capacity in our laboratory," Asuman Lukwago, permanent secretary at the Ministry of Health [MoH], told IRIN.

"Previously, we could take those specimens to Atlanta [in USA] and this could take us about two to three weeks when we are fidgeting, and this could allow time for transmission of epidemic to take place. But now, we can quickly confirm and therefore alarm the public and everybody becomes cautious."

Who is involved?

In the event of an Ebola outbreak, MoH partners with WHO, CDC, MSF, the Uganda Red Cross Society and NGOs to provide technical and laboratory support, a communications campaign, as well as surveillance, according to Makumbi.

"If we got a problem [outbreak], we contact our development partners and inform them. We call emergency meeting and reactivate the national task force, which is always on standby to respond," said Makumbi.

The task force coordinates national, district, sub-county and village health teams, local NGOs and outside partners.

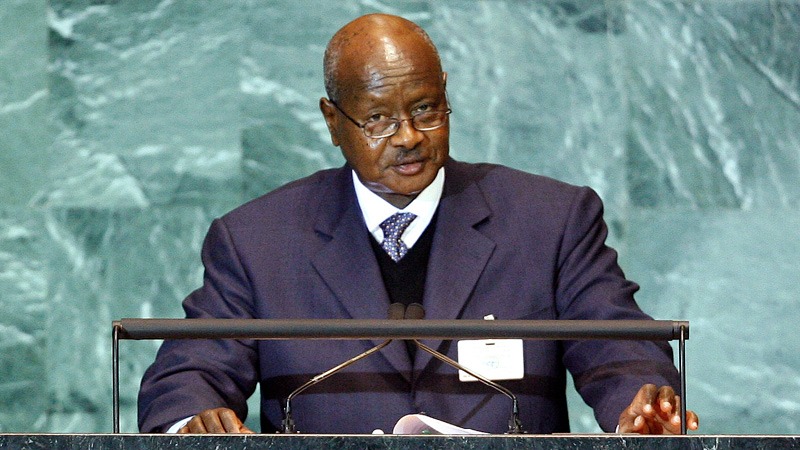

Uganda's political leadership, especially President Yoweri Museveni, is involved in mass public sensitization during an outbreak.

"The top leadership is always appreciative of the efforts on Ebola and other haemorrhagic fevers. When we get the deadly outbreaks like Ebola or Marburg, we inform them. The president [Museveni] himself goes over radio and television to announce the outbreak and tell people of the recommended measures to control it," Lukwago, told IRIN.

"For us, sometimes after a long time of being technical, you may not get easy translation of technical words into what the community can understand better, and the president is good at that. We brief him, give the necessary information and he simplifies it. The word is more heard when it comes from the top leadership of the country, maybe than the technical person."

Why do control measures work relatively well in Uganda?

Uganda's well-coordinated and functional outbreak response system compares well to West Africa countries, according to experts.

MoH, WHO and the district leadership provide overall coordination. MoH and the Uganda Red Cross have worked on contact tracing, case follow-up, and alerts from communities regarding new cases. District hospitals and MoH have worked on transport for picking up new suspected cases as well as for burial coordination. CDC provides case investigation, epidemiological response, data management and laboratory testing.

MSF, MoH, and the district hospital provide clinical care and treatment. Other partners provide supplies and support through MoH.

CDC's laboratory in Entebbe provides rapid Ebola and other VHF diagnostic testing, and this has helped to identify eight HF outbreaks in the last four years. On occasion it has sent teams to try and identify the animal source of the outbreak.

"Working with MoH, we helped mobilize a response team. to the affected district and provide immediate assistance. These factors have contributed to the ability of Uganda to have a well-coordinated and functional outbreak response," Shoemaker, told IRIN.

Why is Uganda confident of coping with Ebola?

"Uganda's experience with outbreaks of Ebola and other VHFs has enabled the country to identify these outbreaks quickly. The country is therefore able to establish a formal investigation and response with all the components that allow for a comprehensive response and containment of the outbreak within a relatively short amount of time," Shoemaker told IRIN.

"Uganda has contained these outbreaks more effectively than West Africa due to West Africa's relative inexperience with outbreaks of this nature. Uganda performs all the same response procedures currently being followed in West Africa, but they are done at a much earlier stage and are typically more quickly coordinated thanks to the collaboration of partners and MoH," he said.

"Because of a history of VHF outbreaks, people in Uganda are not afraid to self-report for medical care if they are sick or have been exposed to a confirmed case. This allows for identification of most new cases as soon as they become symptomatic. These patients can then be placed in isolation and begin treatment before they are able to infect additional people," he added.

"We, too, panicked during the first outbreak in 2000 which killed one of our doctors [Mathew Lukwiya]. Everybody looked at Ebola as a mysterious disease. But from then, we noted that we are always prone to getting Ebola. So every time we have a suspected case, we are well ready to handle the worst scenario. So it has become less of a crisis," Lukwago, told IRIN.

"The existence of our health units scattered throughout the country and veterans in the fight against Ebola is an enabling factor that has helped us to control these outbreaks. We usually encourage the hospitals where the outbreak is reported to have an isolation centre and our veterans rush to help in isolation and confinement."

"These West Africa countries are unlucky in the sense they have not invested very much in the health system like Uganda has done. The affected countries are basically worse off," said Ssengooba.

"In the rural setting, there is almost nothing like a health facility, or if it's there, it has people who can just deliver some basic health care. The whole system is run by people who are mostly volunteers not health experts and professionals," he said.

"When it comes to managing the epidemics, handling patients, wearing gloves, putting up drips, those are things that slightly require trained people, and affected countries right now are trailing in terms of health systems strengthening. That is why the epidemic is spreading faster."

What contingency plans are in place?

Since 2010, MoH in partnership with CDC and UVRI have established a first-of-its-kind VHF surveillance and laboratory programme, with sentinel surveillance sites around Uganda, and equipped and trained personnel to properly identify, report and transport samples of suspected VHF cases. The CDC-funded VHF high-containment laboratory in Entebbe has also been renovated and upgraded to be able to perform many diagnostic tests in a safe and secure environment, allowing rapid laboratory confirmation of suspected cases.

"This programme has confirmed seven VHF outbreaks in Uganda and one in neighbouring DRC since 2011. Since this time, there have been substantial investments made to improve the overall surveillance and alert system in Uganda," Shoemaker, told IRIN.

"As part of contingency plan, the ministry always has catalytic emergency funds, the field epidemiologists and field clinicians who are always on standby and ready to move to the field any time in case of an outbreak," said Lukwago

"Due to the Ebola, every fund which is available will be released immediately and then we can quarrel later. The fear to release funds may cost you lives and more funds, like it's in West Africa. The aim is to make sure that you limit the cases to those who are affected and therefore you don't get more cases."

"The main contingency plan is simply to invest in strengthening health systems. Let's have people who are trained, who know what to do. Give them the right tools to use, and skills," Ssengooba told IRIN.

"Many of these people [health workers in West Africa] don't even have protective gear like gloves, and skills to use them. If people have never used them, you can't bring them [in] during the epidemic and you think they can be effective in using them. People are used to doing things through short cuts," he said.

"We need to ensure the system is built for all conditions that could erupt," he added.

How well is the media deployed?

Lukwago said Uganda has effectively used DHIS2 to report and monitor suspected cases, as well as emails, SMS alerts, and radio and TV talk shows as part of outbreak response plans. MoH has established a permanent Emergency Operations Centre in Kampala to coordinate these activities.

"If we got an outbreak of Ebola in any part of Uganda, a majority of people who have telephones will be able to know in one hour or two hours through SMS alerts. We, too, communicate through radio and television, which majority of people have. By the end of the day, almost every Ugandan is aware of Ebola outbreak," Lukwago told IRIN.

"Our population doesn't doubt any information which we give them. This was found wanting in West Africa where many people doubted whether this was something brought by Europeans or foreigners and so on. So in the process they didn't have confidence in the government information," he added.

so/cb

This article was produced by IRIN News while it was part of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Please send queries on copyright or liability to the UN. For more information: https://shop.un.org/rights-permissions