The Democratic Republic of Congo has a new leader in waiting after the election commission announced on Thursday that Felix Tshisekedi, head of the country’s largest opposition party, is the provisional winner of a long-delayed, now-disputed presidential election. He will inherit a host of humanitarian crises – from Ebola to protracted conflicts – that continue to plague the vast Central African nation.

In previous elections in 2006 and 2011, disputed results sparked violent protests. There are fears that a repeat this time around might see a fresh eruption of political violence, which could worsen one of the world’s largest humanitarian emergencies.

If Tshisekedi is confirmed the winner and replaces Joseph Kabila after 18 years, it will be both historic and contentious: historic in that it would represent Congo’s first ever peaceful transfer of democratic power; contentious due to accusations of fraud and voter manipulation – murmurs even of a possible power-sharing deal behind the scenes between Tshisekedi and Kabila’s preferred successor, the ruling party’s Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary.

The Catholic Church, which has an influential role in Congolese politics and deployed some 40,000 observers to monitor the 30 December polls, indicated to journalists before the provisional result that opposition candidate Martin Fayulu – backed by two of Kabila’s longtime rivals – was the winner. Since the result, which must be confirmed by the Supreme Court before the 18 January inauguration, it has only said the vote tally (7 million to Tshisekedi, 6.4 million to Fayulu, 4.4 million to Shadary) doesn’t match its data. Fayulu himself has denounced the result as an “electoral coup”.

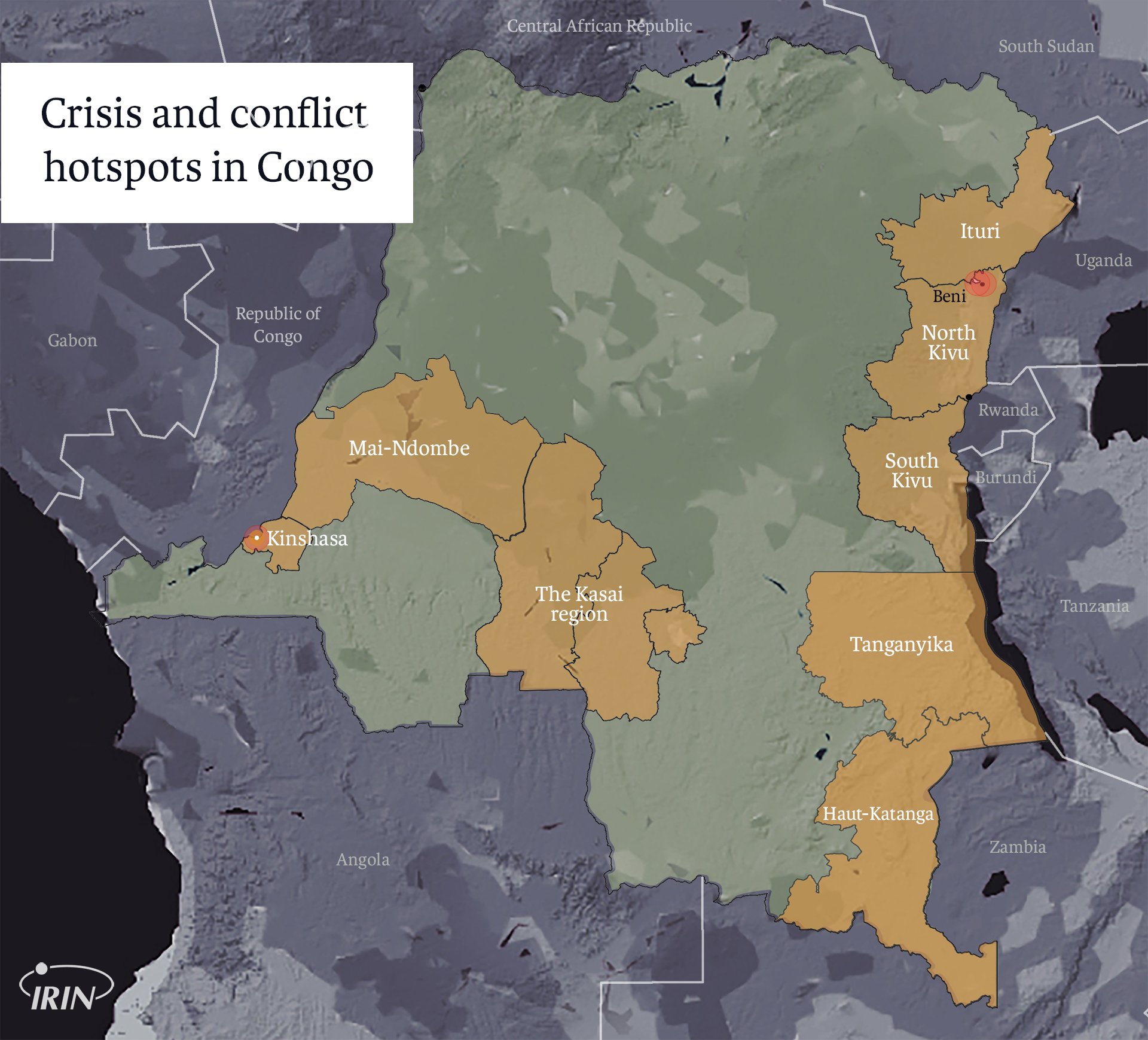

Officially, Congo is not a country at war. But the mineral-rich country, roughly the size of Western Europe, is in the midst of dozens of protracted conflicts involving hundreds of armed groups, including in the provinces of Tanganyika, Haut-Katanga, and Mai-Ndombe.

With some five million people currently displaced, and almost 13 million in need of assistance, the new president faces more than just political problems. Here are four of the most pressing humanitarian challenges he will have to deal with in 2019.

Ebola

Ebola is endemic in the DRC. But the country's current 10th outbreak is its worst, and it’s far from over yet. Not only is this the second largest Ebola outbreak in history – beaten only by the 2014-2016 epidemic that claimed more than 11,000 lives across West Africa – it’s the first to take place in an active conflict zone.

It began in August 2018 around Beni and Mangina in eastern North Kivu province – just as an earlier outbreak in western Equateur province ended – and has also affected Ituri. It has now killed more than 380 people and spread to more densely populated urban areas including the trading hub of Butembo – home to about one million people.

Read more | Q&A: Congo Ebola outbreak at critical juncture, says top WHO official

While previous outbreaks were confined to rural areas, and therefore easier to isolate, this one is near a busy border region, which has raised fears the disease could spread into neighbouring countries, including Uganda, South Sudan, Rwanda, and Burundi.

The fact that the epicentre of the outbreak is in a restive part of the country awash with armed groups has hampered the emergency response, the UN said in a report last month. Violence has triggered displacements from and to Ebola-affected villages, most likely contributing to the spread of the disease.

North Kivu and South Kivu

Eastern Congo, which was the epicentre of two devastating wars, 1996-1997 and 1998-2003, is still caught up in near-constant fighting, fuelled by the presence of more than 130 armed groups, often vying for control over lucrative mining operations and other natural resources.

The provinces of North Kivu and South Kivu have witnessed regular killings, rapes, mutilations and other atrocities against civilians. The number of human rights violations in North Kivu alone amounts to one third of all the abuses recorded in the DRC, the UN said in a report in December that documented “hundreds” of extrajudicial killings and cases of torture and sexual violence against civilians over the last two years.

Read more | In-depth – A decades-long cycle of war

Widespread violence, largely attributed to armed groups, provoked mass displacements of people, the UN said, while allegations of complicity between some army members and armed groups in the worst-affected territories of Lubero and Masisi increasingly threatened the already vulnerable civilian population.

The security situation also deteriorated in 2018 in nearby Beni Territory, which is plagued by armed groups and is the epicentre of the current Ebola outbreak.

Meanwhile, in South Kivu, armed conflict, sexual violence, serious human rights violations and risks of forced recruitment into armed groups all contribute to displacement, according to the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR. The province has also experienced inter-communal violence, including an uptick in skirmishes ahead of December’s elections, and it hosts more than 40,000 refugees from neighbouring Burundi.

Kasai

In 2016, conflict erupted in Kasai between the Kamuina Nsapu anti-government movement and Congolese security forces and soon engulfed the entire region. An estimated 5,000 people were killed and more than 1.4 million displaced.

Although the authorities have since regained control of much of the region, ethnic tensions and political disputes continue. And for those who have come back home, the destruction caused by years of fighting means that returns are accompanied by significant humanitarian needs.

The Kasai region already had some of the poorest and least developed provinces in the DRC, even before the 2016 conflict. After the violence began, people were unable to grow crops, driving a 750 percent rise in food insecurity and a massive increase in malnutrition rates. In May last year, UNICEF reported that 400,000 children were “at risk of death” in the Kasais because of food shortages.

A November 2018 report by MSF documented alarmingly high levels of rape in region. The health NGO said it treated 2,600 victims of sexual violence between May 2017 and September 2018.

Read more | Briefing: Problems multiply in Congo’s Kasai

Compounding an already stressful humanitarian situation, more than 300,000 Congolese nationals who were expelled from neighbouring Angola in October, crossed over into Kasai, piling a new emergency on top of existing ones in an already fragile region.

Most returnees appear to want to move away from the Kasai border areas, toward other destinations inland, which could help ease the humanitarian strain. However, expulsions from Angola are not an isolated event and more returnees could arrive in the coming year.

Ituri

Inter-communal tensions led to conflict and displacement across Congo last year, but perhaps most noticeably in Ituri province. In the Djugu territory in December 2017, violence between Lendu (farmers) and Hema (herders) escalated and spread. By March 2018, 300,000 people were internally displaced.

Secondary displacement was also reported as people moved in search of food, healthcare, and shelter due to a lack of assistance, while tens of thousands of people crossed the border to Uganda to become refugees.

Read more | Politics and oil: the unseen drivers of violence in Congo’s Ituri Province

Although displaced people began returning to Ituri in March, Djugu has seen renewed conflict between armed groups and the military since September. Of the 7,985 households that returned, about one third have been displaced again.

Displaced households do not have access to their fields, while returnees have lost two successive agricultural seasons, according to a report from the Famine Early Warning System Network, or FEWS NET.

In December, UNHCR said it had received reports of close to 100,000 newly displaced people in Iruri. It added that an estimated 88,000 houses in Ituri and North Kivu have been destroyed or damaged due to violence.

(Initially published on 20 December, this story was updated following the provisional election result on 10 January.)

si/ag